It’s been a good PR spring and summer for dictators, old and new. Earlier in the spring, an article in the American Conservative waxed poetically over Vlad the Impaler’s leadership lessons for the rest of us. Some conservatives, in the meanwhile, have been eagerly promoting a more recent dictator, Hungary’s Victor Orbán, as a model of a great Christian leader. Across the pond, Stalin and Lenin are enjoying a renewed popularity in Putin’s Russia. And finally, just this past week, Elon Musk got historical too, suggesting on Twitter that “Perhaps we just need a modern day Sulla.”

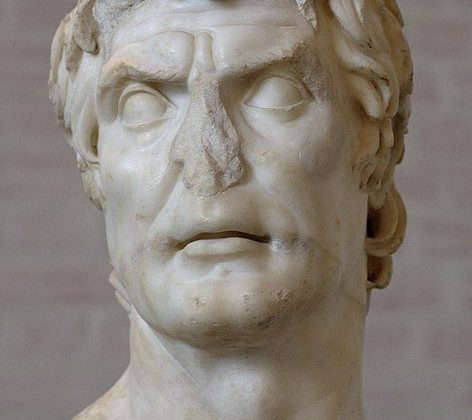

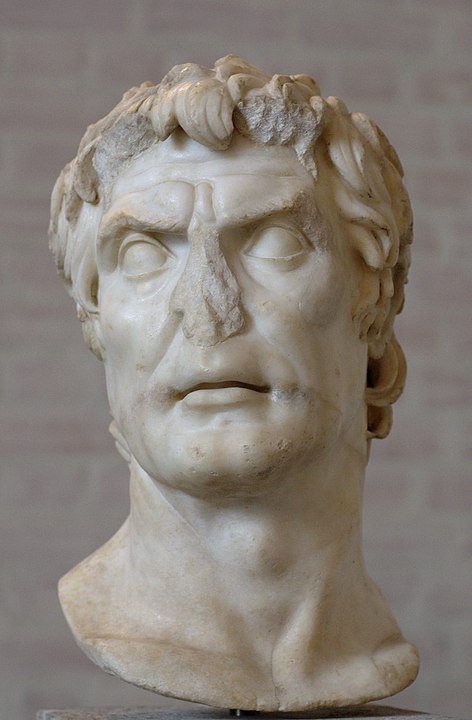

Historians had excellent responses to each of these taken singly. In particular Miles Smith cautioned conservatives about the dangers of idealizing Orbán, whose ostensibly Christian government is, in reality, nothing of the sort. And Greco-Roman military historian Bret Devereaux explained in detail why Sulla, a horrifically blood-thirsty dictator who implemented a political purge, was really a horrible leader too. Joel Christensen highlighted one of the more poignant primary sources about Sulla on his blog in response as well. But these excellent explanations and responses from experts to individual instances of dictator fan-boying still leave a key question unanswered about this phenomenon as a whole: why is there such fascination right now with leaders whose main claim to fame has been extreme violence against their own people?

First, it is important to note that anyone expressing a desire for a Vlad or a Sulla to take charge right now is making a dangerous presumption—that it will be someone else who will be subject to the bloodletting that has invariably accompanied these leaders’ rule. Considering the historical trends about how dictators operate, however, this assumption of personal safety is quite risky. Being in the “in” circle for someone like Vlad or Sulla or Stalin was no guarantee of longevity. Plenty of allies were suddenly declared enemies and executed tout de suite. Not a gamble I would personally want to take. But there is more.

Idealizing horrible dictators while our own democracy burns is decidedly a bad sign about how those who think that way think about the rest of their neighbors. This way of thinking shows a devaluing not only of democracy, but also a devaluing of people and fellow-citizens more generally. The two are, after all, inextricably connected: for a democracy to be successful, the members of the demos must value each other and respect each other enough to consider the voice of other citizens important even when disagreeing.

If someone really wants to live in a government led by a Vlad or a Sulla, they are welcome to gamble their own life, freedom, and personal dignity. But government is not a matter of individual choice; there is no getting around the collective nature of it, especially in a democracy. And so, it is a bad sign for how we view fellow-citizens if we wish for a bloodthirsty dictator to take over and “fix” society’s problems in the only way he knows—a thorough purge.

Ultimately, the call for dictators to come and take over is a call to stop civil discourse and conversations and, instead, to solve “problems” in society via extreme violence. But—and this is key—history shows that such “solutions” never truly worked. Instead, they have served only to destabilize societies further. As Harriet Flower, historian of the Roman Republic, has argued, the Republic was never quite the same after Sulla. We can trace the ultimate downfall of the Roman Republic to Sulla’s reign of terror, which set up a new generation of wannabe dictators, like Caesar and Pompey, to follow in his steps with their own dreams of violent domination.

And when Octavian (eventual Augustus) formed the Second Triumvirate in 43 BCE together with Mark Antony and Lepidus, the first thing the trio did was adopt Sulla’s old strategy of proscriptions—publicly posted kill-on-sight lists of citizens. The list included the politician and orator Cicero, who had spoken out so eloquently against Mark Antony before. After his execution, Cicero’s head and hands were nailed to the rostra, previously the site from which speakers addressed the people, as a warning of the new regime’s approach to free speech. But we don’t have to go to ancient history to look for examples of what dictators do. If we think about more recent history, one need not look further than Putin’s Russia, as a legacy of a century of dictators is bearing fruit in yet more violence, directed both externally and, as far as suppression of opposing voices requires it, internally.

This is not a world anyone should desire. Yes, we all would like to be in the right and to get our own way. The fascination with dictators on the part of people like Musk merely reflects the innermost desire that we all have since infancy to have the power to do whatever we want. But then life for all of us is a process of (ideally) continually learning to set aside our own wants and needs in order to get along with others—parents, siblings, one’s spouse and children, co-workers, neighbors and church community and, ultimately, fellow-citizens. Sure, killing off anyone one disagrees with could be one way to win a dispute, as historic dictators remind us. But it is not a path we should ever consider or, worse, idealize openly.