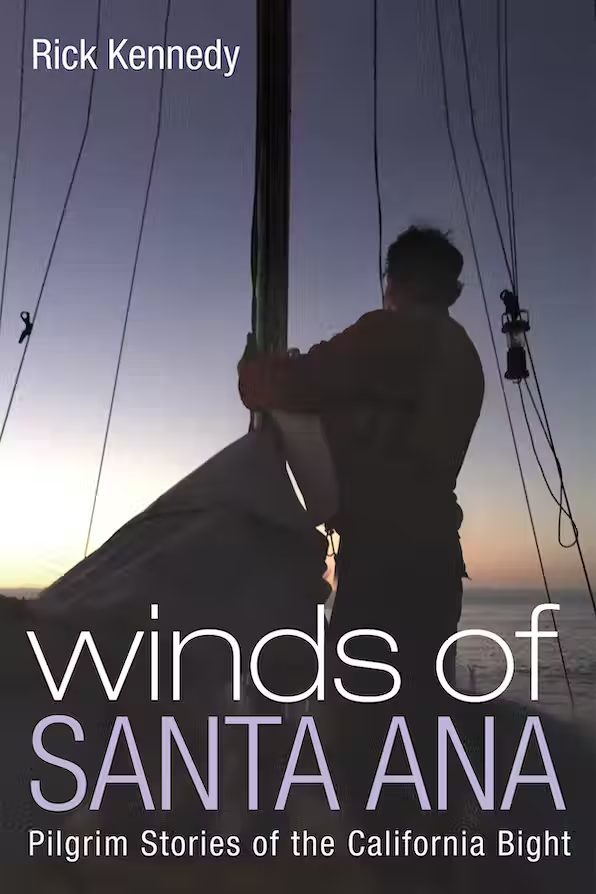

Today’s interview is with Rick Kennedy, Professor of History at Point Loma Nazarene University, and the author of a number of books and articles on topics as wide-ranging as the history of logic, mathematics, architecture, astronomy, education, historiography, and Christian thought. Rick is basically the personification of the liberal arts at their best! While he wrote this interview before setting sail, he is at sea today, probably looking a lot like the cover of his most recent book.

You are a prolific writer, but also a widely-ranging teacher. I remember talking with you about Herodotus at a previous CFH! So, in honor of this recently concluded academic year, what was your favorite class to teach this past year?

The best thing to happen to me as a professor was when, after ten years of teaching American history, a dean, sitting on the other side of his desk, told me that I will teach two sections, every semester, of World Civilizations: Ancient to 1500. I told him it would take me five years of teaching before my class would be any good. He said “fine.” That was twenty-eight years ago. Oh, what a blessing! I was set free to read and wander, wonder and read. I still say all sorts of things in class that I really don’t know. After the students have left the room, I often think: “Is what I said true?” But the beauty of the teaching cycle is that I can go get a few books and next semester teach that lecture with more confidence.

So, I have to say, year after year, the most fun I have is teaching general education. I teach eighteen and nineteen year olds to appreciate the various holds the ancient world has on us so-called modern civilized people. My favorite book to teach is Herodotus’ Histories. What a rollercoaster of post-modern fun to sit and listen to what Herodotus has to say about civilization. Many of my students tell me years after the class that Herodotus is their favorite memory.

Four years ago, our college started an Environmental Studies program in which I teach “Wilderness in the American Mind.” Here again, by next year, my fifth, my class should be approaching being good. What better career can a guy like me have than teaching students the joy of reading Cotton Mather, William Bartram, John Muir, and Rachel Carson (her sea books, not DDT)? Last semester I ended the class with discussing Lady Bird Johnson and her goal to make America more beautiful. I hit upon Lady Bird only in mid-semester and need to read more about her before I teach again next year.

It seems like you just can’t get away from Cotton Mather since writing a biography on him a few years ago. Could you tell a bit more about your project on his work this summer? What in particular continues to fascinate you about him?

Cotton Mather is endlessly fascinating. He is so very human, so Bible-driven, and so dang interested in Everything! I rate historical figures by how much I would like to be at a dinner party with them. (This is not a good thing, but I do it anyway.) Imagine the fun of sitting around a dinner table, dishes cleared, late into the night with Cotton Mather, Herodotus, and Richard Henry Dana Jr. There are people smarter, wiser, and better informed who I should sit through a dinner with, but those are my three that will still be interesting long after midnight.

Right now, I am writing about Cotton Mather’s three-hundred or so page history of the Jews after Josephus. Mather is doing what he does best–he is bringing into New England the books, people, and ideas of Europe (in this case from Calvinists in Rotterdam and Sephardic Jews in Amsterdam). One of his main goals with this history is to teach political and religious toleration. He praises the popes, kings, and sultans of history that did not persecute the Jews and, instead, appreciated Jewish help. As usual, it is not until a hundred years after he dies that American historians start writing about history the way he did.

I enjoyed Cotton Mather’s Spanish Lessons: A Story of Language, Race, and Belonging in the Early Americas by Kirsten Gruesz. That is my Cotton Mather! Gruesz is a professor at UC Santa Cruz and shows how Mather is a creole thinking big thoughts about Mexico!

You mentioned that you are about to embark on a 12-day sailing trip! Having read your most recent book, which I enjoyed reviewing, I know this is your happy place! What are you most looking forward to on this particular voyage?

I leave for Santa Barbara later this week. It will take me five or six days of sailing to get up there. I expect to be traveling, at best, between four and five miles an hour. I will be Julian of Norwich for a couple of weeks–just not bricked up. I will be walled within the hull of a small boat (a Herodotus reference). I will be showered by love and beauty no matter what the weather. Being a history professor has been a wonderful blessing. It offers me leisure, leisure to listen to a creation so much greater than the mere present. Being at sea is a mystical experience.

I am going to give a talk at the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum called “When Science and Art Met in the Coast Survey of the Santa Barbara Channel (1849-1860).” My talk is designed to be pleasant. The earth will not be shaken. No original thought will be spoken. I will simply affirm the lives and good work of people who sailed in the Santa Barbara channel long before me. Being at sail puts all things in perspective and a maritime museum will supply a friendly audience. Smallness and slowness will be affirmed. By the way, I was excited to read that Eric Miller is writing a book on localists and thinking local. Eric is a big thinker who appreciates smallness.

What are the broader questions that fascinate you in your reading, thinking, and writing? Any particular books that you have read recently that really stood out?

Like everyone else in our profession, I am wrestling with where academics is going, especially Christian academics. We are increasingly good at supplying to the world economy STEM-trained people, but STEM in the sociology of knowledge is shallow. Sadly, humanities over the last fifty years has increasingly been scientized and philosophized to the extent it is mostly an un-alphabetized part of STEM.

I am reading, right now, McGrath’s biography of C.S. Lewis. I am reading it for the third time. Actually, I am listening to it a third time on audible as I exercise. I find the story of Lewis to be a comfort. He goes through two World Wars and the decline of academic humanities all the while becoming more sensible to the greater truths, to the biblical cosmos, to mere Christianity. George Marsden’s biography of Mere Christianity is a wonderful book. My Russianist colleague, Bill Wood, recently lent me Collin Hansen’s Tim Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation. After reading it, Bill and I wondered if it wouldn’t be better to dump the CCCU and go back to having Bible Colleges. The Bible is bigger than Liberal Arts. A few years ago I read Eugene Peterson’s autobiography The Pastor. Wouldn’t it be better if a bunch of Christian colleges–not all, but a bunch–simply went back to teaching how to read well, especially how to read the Bible.

You are so inspiring, Rick. I am especially grateful for the account of the way you embraced the Ancient Civilizations course not as an imposition and a burden but as an opportunity to learn and deepen and discover.