Many know the night.

This was the message I heard on the afternoon of September 10, 2002, while sitting in the hushed, overwarm, overcrowded chapel of Middlebury College, where I was just beginning my sophomore year of studies.

My friends and I had arrived early to be sure of getting a seat. We ended up towards the middle of the chapel, squashed together in one of the hard, wooden pews. As we waited for the lecture to begin–for this was not a church service but another kind of service, suited to us in another way–I looked up and saw my faculty advisor standing at the second-story railing, his two sons crammed in front of him to get the best possible view.

“That makes sense,” I thought. “This is going to be dark and difficult, but when will those boys have a chance like this again?”

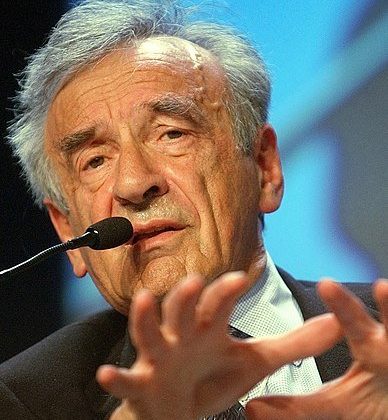

Presently the speaker was introduced and began his talk. I had read his most famous book, Night, in my eighth grade literature class, and his name, Elie Wiesel, was known to most of my college-mates. As the summary on the back of my copy of the book explains, “Night is one of the masterpieces of Holocaust literature….the autobiographical account of an adolescent boy and his father in Auschwitz.” At the time he was taken to Auschwitz, Weisel was no older than my professor’s sons.

So my friends and I had left our studies and our practices and our other activities with the expectation of experiencing something meaningful and special, and probably also dark. We expected him, due to the date, to connect his words somehow to the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, to help us make sense of what had happened. And I think we also wanted just to see this man, to see if there was any noticeable mark on him, in body, speech, or personality, that would mark him out to us as one of the Suffering.

We settled, as students do, into our usual lecture mode, listening but also occasionally wondering whether the dining hall would have its famous chicken strips tonight or not. But after a while, my ears perked up a little more as I started to notice that the message I was hearing was not what I had expected.

I had expected to hear something like the narrative I had read in Night, something about suffering and terrorand hope and God and maybe the humanities, since we were at a liberal arts college, after all. Or, I thought, Wiesel might speak about his most recent book, or use the opportunity to discuss some political cause he hoped to champion. He had won the Nobel Peace Prize—perhaps he would exhort our generation to pursue peace and not war?

But instead, he said something unexpected. Although, as the campus newspaper reported, he talked at length about September 11, the gist of his message was about suffering and rememberance. It was about compassion. And although I don’t remember his exact words, one message in particular stuck out to me. It was something to the effect of: “Yes, I know the night. But do not forget this: many know the night.”

Many know the night, indeed.

You see, Wiesel told us (and my memory is paraphrasing him here), the Holocaust was a tremendous tragedy, a suffering so great that it threatens to overwhelm our concept of suffering altogether. We fixate on the Holocaust as the greatest suffering of all, to which no other suffering compares. We do not wish the Holocaust to be repeated, so we teach our young people its horrors. And this is right. We must remember.

But is it true that the Holocaust is so terrible that no other suffering can compare? Does the survivor of such a thing have a monopoly on suffering? All suffering deserves our compassion.

This we must not forget.

I felt, hearing these words, as if a blast of wind had pinned me to the back of the pew, stealing away my breath and threatening to unleash something wild and deep within me.

For I myself knew the night. No, I did not know suffering anything like as terrible as Wiesel’s, and yet I had experienced darkness. And yet it seemed that few people had ever really noticed. Following the sudden death of my mother five years before, when I was thirteen, most of the people close to me had organized my life around their own grief, their own suffering, their own needs. I was too young to push back against this or know it was wrong, and so I did not grieve, but treated myself as there only to support others. I did not even really cry.

And now here was Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor, saying to me, out there in the audience: I know that many have seen the night, perhaps even you. And that matters to me.

As a student from a different university quotes Wiesel as saying, “Memory [is]n’t just for Holocaust survivors. The people who ask us to forget are not our friends.” This was the theme, too, of his Nobel prize acceptance speech.

Elie Wiesel was an extraordinary person by any standard. But what I had not expected was that part of his extraordinariness would consist of his reaching beyond his own pain and even the collective pain of September 11 to tell a silently wounded college student that her own suffering also mattered, and to encourage a group of young people not to dismiss suffering of any kind. He had not come to our college, it seemed, for the accolades. He was there in the chapel that day because he truly cared for all those among us–-likely most of us–who might also know the night.

And what he said was true. Many do know the night. I know I do. Do you?