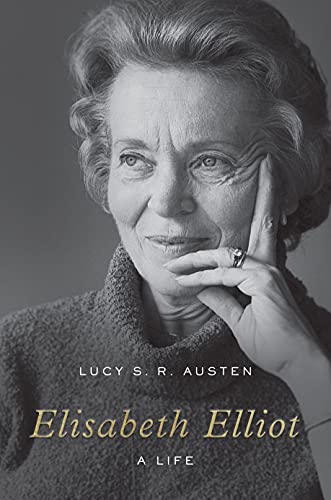

Lucy S. R. Austen’s biography of Elisabeth Elliot is scheduled for release this month. We are grateful that she visited the Arena to tell a little bit about this project, her research, writing, and “rest between two notes.”

You mentioned that you started work on this project a little over a decade ago. How did you decide to write this book? Can you tell a little bit about your own story here: what was it like to live (intellectually) with Elisabeth Elliot for these past ten years?

I got started because I was writing a homeschool high-school English textbook. Students would read a brief biography of eight different authors, a piece of each author’s work, and lessons based on some element of those works. I had read a bit of Elisabeth Elliot’s writing and knew that I wanted to include her novel, No Graven Image, in the readings. My practice at the time was to gather a handful of biographies of the writer in question, read them and take notes, and then write my own three or four page mini-biography. And when I went looking for biographies of Elisabeth Elliot, there weren’t any! I ended up having to go directly to source material to write about her, and I was intrigued by what I found. At some point my mom said, You should write a biography of Elisabeth Elliot. I was homeschooling two little kids and we were moving every six months to a year for my husband’s job and I thought, Maybe when the kids are grown up. And then one night I woke up in the middle of the night and my brain was busy creating various outlines for telling her story. At that point I thought, I guess I am starting this project now!

The first few years of the project I wasn’t writing the biography yet, just doing research and conducting interviews, and every time I finished an interview, I came away feeling like that person needed someone to write about them next. People are amazing! It was a huge privilege for me, for people to share their time and experiences with me, and a very sobering responsibility. And then once I started writing, there was the added layer of sifting through all the data to find the threads that run through the years. Spending so much time with the life of another human being has been–humbling, fascinating, upsetting, educational, moving. As with anyone you live with for very long at all there are ups and downs, and things that bother or bemuse you and things that you enjoy about the person. It’s strange to feel that in some ways you know someone very well indeed, and on the other hand if you ran into them on the street, you’d be strangers. Many times I’ve felt like when it was time to step away from my desk and go be with other people, I couldn’t talk intelligently about anything else because this other life was taking up all my headspace.

Can you give us a taste of something surprising or intriguing that you have found in your work on this book?

One interesting sidelight came in teasing out the identities of some people who Elliot was concerned might try to initiate contact with the Waorani—the same people she was hoping to approach–because she was afraid that a commercialized attempt would mess up the chances for missionary work. In the process I discovered Jane Dolinger, who was an adventure-travel writer a little younger than Elliot, who wrote eight books and hundreds of articles. She traveled in Ecuador in 1956 after the missionaries were killed, purportedly to look for the Waorani, and her book The Head with the Long Yellow Hair came out the year after Elliot’s Through Gates of Splendor (and added some non-existent head-hunting, witch doctors, and fabulous emeralds for further excitement).

In a lot of ways the two women were polar opposites—Dolinger wasn’t afraid to play a bit fast and loose with the truth to sell a story, she played up sexiness, she played up adventure; Elliot was quite factual in her reporting, she emphasized spirituality and religious faith, and she directly contradicted the idea that she was out for adventure. At the same time, they were both women doing unexpected things in unexpected environments, and they were both selling books at least in part because they appealed to the same interest in what were seen as exotic and unsettled locales where anything could happen. It seems likely that some of Elliot’s initial commercial success as a writer was due to this type of interest. I find it a really interesting comparison.

What are the broader questions that fascinate you in your reading, thinking, and writing?

For a while now I’ve been thinking about history and time. Both in my research and in my own life I see the impulse to “save” everything, and the physical impossibility of doing that. I’m just starting his book How to Inhabit Time, but James K. A. Smith says, “Forgetting is the exhale of a temporal being,” and that rings true to me. No matter how many letters you save and donate to an archive, no matter how many times you ask your parents to tell you their stories and write them down, when an individual dies so much goes with them. How do we live with knowing how fragile and temporary everything is? How do we choose what to try to save? How do we make sense of the fragments we can hang onto? How do we think about the self, Rilke’s “rest between two notes,” when it takes a whole lifetime to gather all the data and yet by then so much is lost to us in the fog of time?

I am sure that you are sick of hearing this question, having just finished one very ambitious and lengthy project, but what is next for you?

In the long term, I’m not sure. I think there is plenty of room for more scholarship on Elliot and I’m thinking about possible projects there. I really enjoyed the research involved in writing a biography, and I’d love to do another one. In the short term, I’m revising my textbooks for a new edition, and I’m working on preparing some of my research materials to go to the Billy Graham Center Archives at Wheaton College and be a part of their holdings on Elisabeth Elliot, which I’m particularly excited about.