As historians, we display the same love of searching for agency as any mom who enters a really messy room with trepidation yet determination—every toy box has been emptied, and the Legos strewn across the floor dare you to walk across this treacherous terrain as saints and sages of ages past once did upon burning coals, but with less painful effects. And so, in our search for agency in moments like these, we ask the all-important question: WHO DID THIS? For historians, there’s also the related “why did they do this?” question, which is very important once we answer the first one.

Usually, for both moms and historians, the agency that we examine when we ask this question is that of people. It is people who leave Legos for others to injure themselves, or who drive the course of history more generally by their ideas, beliefs, actions, decisions, etc. But historian Kyle Harper’s most recent two books remind us that we, humans, may be less in control than we think, when it comes to such driving factors in history as the environment in which we dwell. Certain features in our environment, including climate and disease, have shaped history more profoundly than we’ve given them credit, as William McNeill and Jared Diamond have previously argued. But it’s definitely time for an update on the conversation they started. Because of length, I have split this discussion into two parts, and in this post, we begin with Harper’s 2017 book The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire.

Before reading this book, I had previously read and appreciated Harper’s magnificent From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity. Highly recommend. But The Fate of Rome is a different sort of book: while Harper is a master of all the traditional primary sources in the ancient historian’s arsenal (literature, archaeological evidence, inscriptions, papyri, coins, etc.), he also makes use of the most recent modern scientific research to fill in the gaps and present a much richer story. He calls these “natural archives,” and explains their significance as follows:

“Natural archives come in many forms. Ice cores, cave stones, lake deposits, and marine sediments preserve records of climate change, written in the language of geochemistry. Tree rings and glaciers are records of the environment’s history. These physical proxies preserve the encoded record of the earth’s past. Equally, evolutionary and biological history have left a trail for us to follow. Human bones, in their size and shape and scars, preserve a subtle record of heath and disease. The isotope chemistry of bones and teeth can tell stories about diet and migration, biological biographies of the silent majority. And the greatest natural archive of all may be the long strands of nucleic acids we call genes. Genomic evidence can cast light on the history of our own species as well as the allies and adversaries with whom we have shared the planet.”

Both professional Roman historians and amateurs have long been fascinated with Roman success and resilience and reasons for both. We can (and should) also talk about the darker side of Roman imperialism–“they make a desert and call it peace,” the Caledonian chief Calgacus famously is reported to have said, according to the Roman historian Tacitus. But again, this means acknowledging the Romans’ agency in acquiring said empire. So, the question then is: why did the Romans amass an empire, and why did this happen when it did? Just what did these plucky residents of the malaria-ridden village on the Tiber river do to grow into a Mediterranean-wide empire? After all, this is not what everyone else around them was able to accomplish, and we’re not sure if some (or most) of their neighbors even desired such an empire.

Based on a vast array of evidence, much of it (in the case of “natural archives”) not even available until the past decade or two, Harper argues that both Roman success and eventual crises and partial collapse were not just the result of factors that historians starting in antiquity have traditionally explored—e.g., government, the military, pressures on the frontiers, religion, etc. Rather, the environment—including climate and disease—had always been a lead actor in Roman history, directing both the rises and the falls. The period of Rome’s greatest success and expansion, Harper showed, fell during what he calls “Roman Climate Optimum” (RCO).

Lasting from ca. 200 BCE to 150 CE, the RCO was a period with just the right temperatures and annual rainfall to afford the highest yield of crops in the broadest range of the Roman Empire. As a result, this was a period of prosperity and population growth. After all, if you can feed your people, life is much better! Strikingly absent during this period, Harper notes, were any pandemic events.

Still, genomic evidence shows that life during the RCO was nasty, brutish, and short. Life expectancy at birth in Roman Egypt was just 27.3 for women and 26.2 for men. Speaking of short, Harper notes the importance of height as an indicator of individuals’ health and resources. “In the developed world, we are now about as tall as our genes allow, and in broad strokes, modernity has given humanity almost half a foot lift.” Italian men post Roman conquest were, on average, just 5’4.5’’, while women were just under 5’. Why is this?

Well, food scarcity for some was always a reality even during the RCO, but even more of a factor for children’s growth is disease. Repeated bouts with highly dangerous diseases leave marks within the body, stunting growth. This evidence can easily be read in bones and teeth. Romans were, overall, very sickly people.

One particularly striking set of data for me was seeing the mortality chart for the city of Rome, broken down by averages for each month of the year. Rome’s population in the first century CE, during the height of RCO, was 1 million! This will be unrivaled again until, possibly, medieval Baghdad. But people in Romulus’ glorious city died in droves.

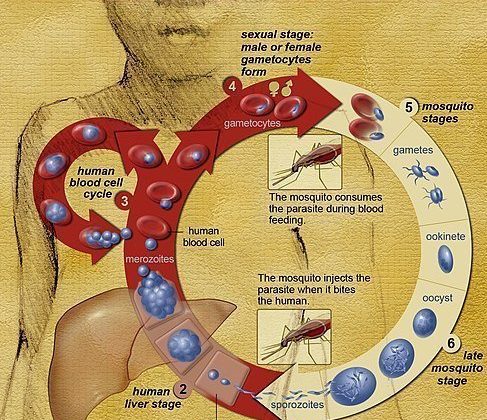

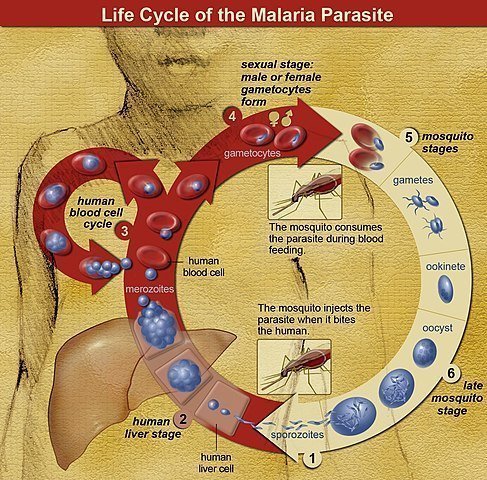

Today, we expect winter to be our sickest season: this is when the flu goes viral. Covid too now rages especially heavily in these cold months, when everyone is indoors. Basically, winter is the season of rough respiratory illnesses. We expect this. What we don’t expect—and, therefore, it initially surprised me—was that in Rome, there were two heavy seasons of mortality each year. Yes, winter was one, for the same reasons as for us, except without modern medicine. But summer was the other, because summer was malaria season, and generally a ripe time for all kinds of parasite-born illnesses.

As the empire expanded, the Romans took the show—including all their diseases—on the road. In every location, “The empire’s arrival led to the hasty construction of the first town, in Roman style, with baths and aqueducts, drains, heating systems, and latrines. Despite the amenities, a reasonable answer to the question ‘What have the Romans ever done for us?’ might have been ‘Got us sick.’ Mortality rates went up.”

But all of this was during the Golden Age of sorts, the period of the Roman Climate Optimum. Thereafter, things got worse and quickly. From ca. 150 CE to 450 CE, the Roman Transitional Period saw a gradual slight cooling of regions in the empire along with reduction in rainfall in certain regions, especially in north Africa. Regions that used to grow wheat gradually stopped producing, so the empire’s food supply went down. Way down.

This was also the period of several severe pandemics raging through the empire, beginning with the Antonine Plague (likely smallpox) ca. 165 CE. The Third Century Crisis saw horrific political upheaval throughout the empire, where emperors were getting assassinated left and right. And that’s not counting additional contenders like Queen Zenobia of Palmyra who made a very determined (but ultimately unsuccessful) takeover attempt in the 260s. Harper argues that while traditional narratives have been writing the horrific Plague of Cyprian (likely a filovirus, related to Ebola) into the mix of the Third Century Crisis, it is more appropriate to see this plague as the factor that plunged a tottering empire into full-blown crisis.

Finally, the period from ca. 450 CE to 700 CE, was the “Late Antique Little Ice Age,” with a further environmental impact on agricultural productivity and, therefore, food supply. And there were more pandemics to boot. The bubonic plague, in particular, basically just never entirely left after the age of Justinian, but kept circulating and periodically resurfacing well into the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. Taking advantage of the weakened peoples of the former Roman Empire, a new prophetic movement that arose in the Arabian Peninsula began its own steady path to empire by conquest.

Harper emphasizes in conclusion the young age of many infectious diseases—the human co-existence in the environment with various critters, visible and invisible, has made both evolution of old diseases and emergence of new deadly diseases possible. This is a story that he picks up in greater detail in his most recent book, Plagues Upon the Earth: Disease and the Course of Human History, which I will discuss in Part II tomorrow.