In Our America, Ken Burns keeps the pictures still—and just as piercing

Our America: A Photographic History by Ken Burns. Knopf, 2022. 352pp., $80.00

In late 2022 Knopf published Our America: A Photographic History by Ken Burns. Weighing in at 6.3 lbs in the mail, it is a weighty and beautiful book in every sense. The subjects of the photographs go beyond the mundane. Each image gets its own page and each would be worthy of being framed on its own.

When Ken Burns began making documentaries, people could not believe what he could do with a still photograph. His technique of zooming in and out while layering in narration made scenes seem to be in motion. It was revelatory to see him portray The Civil War (1990) and make the images come alive without film footage.

It is unsurprising that he has an affection for still photography. In the introduction, Burns explains his personal connections to photography through his father and through professors. He has a familiarity with famous photographers, with pictorialism, and other relevant movements and debates. But he describes his film work as “waking the dead.” The images in this book do likewise and certainly invite our attention.

At the heart of this book is the question, “Who are we? That is to say, who are these strange and complicated people who call themselves Americans?” This book is about the U.S. and it is about us. Our America continues Burns’ now seemingly lifelong quest to better understand the American story as our story. The accompanying quest seeks to grasp the ways in which the parts fit into the whole. We can see this also in his UNUM project with PBS. All of those earlier years have gone into this book. Burns writes,“I’ve needed forty-five years of telling stories in American history, of diving deep into lives and moments, places and huge events, to accrue the visual vocabulary to embark on this book.”

Each image in Our America merits its own essay. Arranged chronologically, covering each of the fifty states, the black-and-white photographs with their own pages and minimal captions are, each and every one, thought-provoking. You could spend an hour staring at almost any given one. With minimal captions, they invite the reader to ponder. Explanations and longer captions can be found in the back. The photos are beautiful, and they are largely images of people, our people. Burns writes that “It is our intention, without cloying nostalgia or unforgiving revisionism, to gather up in these images the generous and the greedy, the prurient and the puritan, the sordid and the sensational, the hideous and the human, the miserable and the miraculous.”

Ken Burns has long had a way with photographs and that is as clear as ever in this book. He has selected images, some well-known and some not, which span a range of American experiences and places. He begins in Philadelphia in 1839 and ends with John Lewis in 2016. We see all kinds of people and all kinds of settings and we see the struggles we have had in bringing our stories together. As Burns explains in the introduction, race has a primacy in our national story. This book tells it that way.

In crafting the narrative Burns has chosen not to rely on obscure images alone but to also include well-known images and figures. There are photos by unknown photographers, but others by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange and more well-regarded figures. There are also photos of the famous. We see anonymous picnickers and students and workers, but also Jack Johnson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Pearl Harbor on December 7th, and Jackie Robinson. A familiar thread about our nation is maintained through the inclusion of recognizable figures and scenes. In some ways, this book could be a welcome companion to a high school history textbook.

But there are also the images that aren’t familiar or comfortable. There is an image of Coxey’s Army. We see pictures of Arizona, Colorado, California, and Wyoming that are stunning in their natural beauty and almost foreign in black and white. There is an image of the Hopi. There is a photo of a lynching, too distant to see some of the details but too chilling to be comfortable. We see a typical family in New Mexico beside a photo of Orville Wright in the air. We see children working in factories. Though the book does not significantly depart from a conventional narrative, the images are not all expected and none are unremarkable.

This book is not a departure from Ken Burns’ filmography but a continuation of his vision of American history. We can see connections between these images and nearly all of his films. There are images of early baseball and of the Civil War, of the Dust Bowl, of Johnny Cash, of Teddy Roosevelt, of Hemingway, of Muhammad Ali, of Prohibition, of one of the Central Park Five, and even Horatio Nelson. In this way the book is a companion to his films, as it weaves together all of those narratives into a metanarrative of the nation. It is Burns doubling down on how he has told our story.

Our America is a classic Burns narrative, but it is not a film: It is a book of still photographs. It succeeds in reminding us of the ways in which photography is so different from other ways of encountering the past. When we read history books or other written narratives, some people and types of people loom so large. Women and children, minorities—they are often less visible. But in photography, especially with minimal captions, every person represented is equally present. Children who never dominate historical narratives are just as real as their teachers. Black Civil War soldiers are just as self-defining in how they stare into the camera as any of their white counterparts. To some extent, images communicate what words can obscure. Someone looks into our eyes from the past. Words cannot hide that and we cannot look away. There are no interviews, only our own introspection to accompany what we see.

Our America does not break with typical interpretations of our past. Nor does the book present images in a confusing or cryptic way. But that does not mean it has nothing to say to us. You can recognize John Brown and still be caught in his steely gaze. You can stare at the photo of the Japanese-American baseball team and wonder about each individual member. You can be moved to learn, looking at an image of two older women, that they are attending a Former Slave Convention. You can smile with the girls from North Carolina smoking cigarettes in 1909. Burns has succeeded in showing us our life from many different angles. He invites us to consider who we are and who we have been. What more could we ask?

Elizabeth Stice is Associate Professor of History at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Her essays have appeared at Front Porch Republic, History News Network, and Mere Orthodoxy.

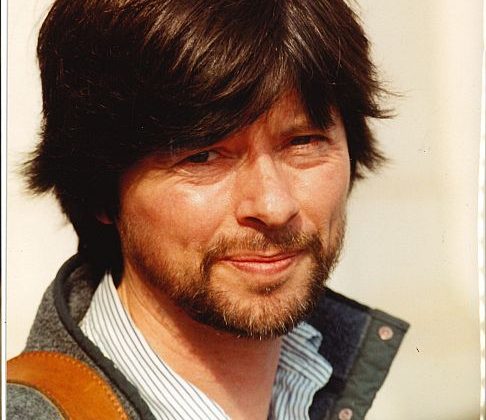

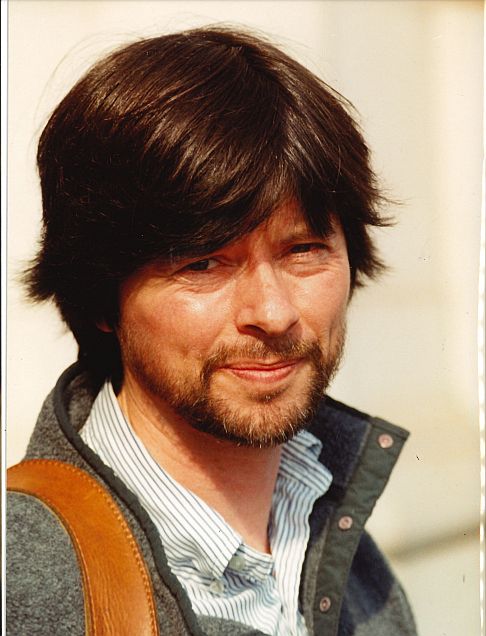

Photo: Wikimedia Commons