“Dead trees are as important to the forest as living trees. Indeed, they are even more important.”

In Book Marks, an occasional feature at Current, we take fresh cuttings from old books (or about old books). They may often be about books, writing, education, communication, and the life of the mind generally, though we reserve the right to snap a sprig of greenery that simply tickles the fancy. (This time, as you’ll see, I mean that almost literally.)

Why look at old books? Because there’s a slat loose in the fence they’ve got us penned up in, and we can jiggle it free to see better what’s going on out there.

With each extended quotation we offer an orienting comment, but that’s not where the action is. The question is whether the words of those who have gone before may speak to you.

*

Carved in stone inside the old Deering Library at Northwestern University is the Latin motto, Inter folia fructus non multa sed bona, a play on words seizing on the fact that both trees and books have leaves. I’d paraphrase it somewhat freely as, “Among the leaves there is fruit, not necessarily abundant, but excellent.” The kind of wisdom cultivated in libraries doesn’t typically capture maximum market share, but nonetheless we may look upon it and see that it is good.

Indeed, the more cultivation that goes on in the library, the more cultivation can go on there. Readers reading often become writers writing, in due course spawning a next round of readers reading, themselves enriched to become writers writing, and so on. The world of books is a biosphere that both sustains and positively generates habitats for still more life, all the way from the subsoil to the canopy. The tree that towers in one generation eventually is laid low while the fungi digest it and its own seedlings rise to fill its place with new forms.

So for this installment of Book Marks, please allow me to snap off one of those sprigs of greenery that isn’t literally about books or the life of the mind—but is laden with metaphorical fertility right under the surface. The German forester Peter Wohlleben collaborated with his longtime translator Jane Billinghurst to create a natively North American edition of his book Gebrauchsanweisung für den Wald (“A User’s Manual for the Forest,” isn’t that a great title?), and it’s a gem. Early on there’s a passage that may make you want to go out walking in the woods, but bear with me and think of it too as a description of “the bibliosphere,” that complex ecosystem of authors, readers, publishers, bookstores, and libraries.

Just like forests, the bibliosphere needs tending. Let’s treat it—and one another, its inhabitants—with gentle, loving care.

Hear what they have to say:

When I talk of the forest, I’m talking about a community. In a forest left to its own devices, trees of different ages and different species grow in the places they choose and that suit them best. Huge mother trees provide their children with the conditions they need to grow up slowly, which leads to strong, healthy individuals. Trees may live for hundreds (even thousands) of years before they finally die and fall to the forest floor.

Dead trees are as important to the forest as living trees. Indeed, they are even more important. Standing dead trees provide homes for woodpeckers first, then the owls and other birds and animals that move in after the woodpeckers move out. Soil exposed when a great tree tips over provides an open space for seeds to land and start to grow, and the massive root structure offers hiding places for small manuals. Finally, an army of decomposers breaks the wood of the fallen tree down into nutrients for the next generation. The clean-up crew’s task is not complete until the last remnants of wood have rotted away. Then, the remains of the trees and the creatures that processed then slip deep into the earth, taking their stores of carbon with them and locking then safely away.

The forest is so closely linked to place that the trees themselves begin to shape the soil, the climate, the frequency of fire, and the path taken by water in the surrounding landscape. . . . The trees, both living and dead, are actively creating the cool, shady, moist conditions they most enjoy.

—Peter Wohlleben & Jane Billinghurst, Forest Walking: Discovering the Trees and Woodlands of North America (Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2022), pp. 4-6

*

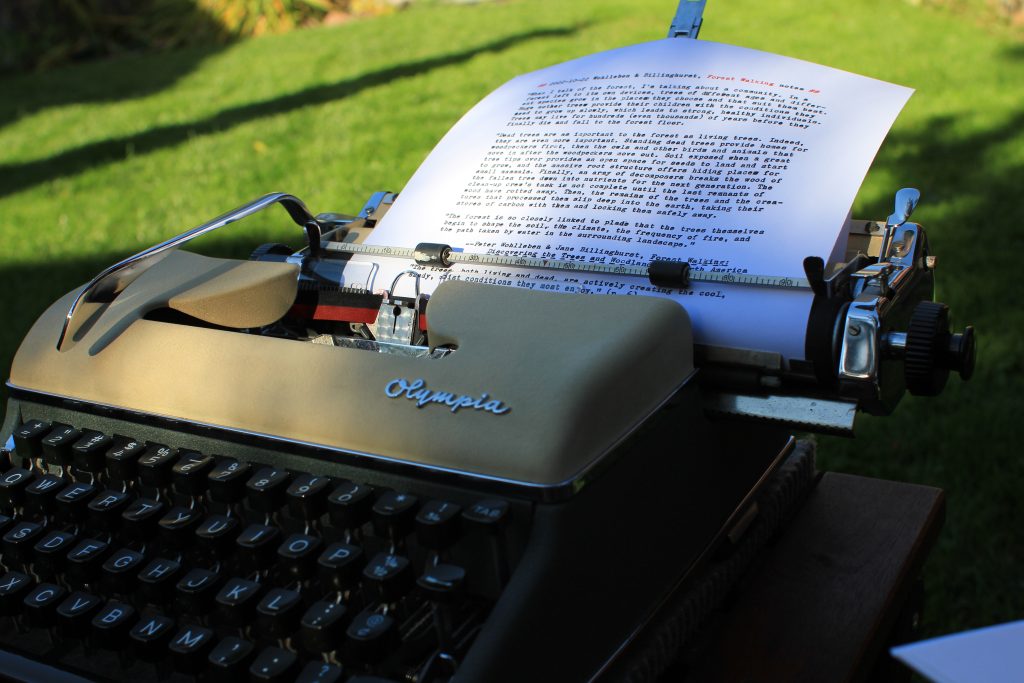

Jon Boyd is keeper of Book Marks at Current. He is associate publisher and academic editorial director at InterVarsity Press, the saxophonist in an improvisational rock band, a user of mechanical typewriters and postage stamps, and (with his wife and daughters) a resident of the City of Chicago.