When you see an Antichrist climbing toward heaven, look out. Then look in.

I swear to God I don’t think I want to know what this piece of writing is actually about. For as many avenues down which I’ve driven thinking about it without arriving anywhere, I can say, at least, that it’s about something. Something sinister, actually. A dark little revelation that I haven’t been willing to, as of yet, completely digest. It scares me. I’m sitting at my keyboard writing this, and I’m scared.

Back when I was in grad school we had a residency in Santa Fe and we had a free day. A free day anywhere in New Mexico is a merciless taunt because an infinite number of free days in New Mexico aren’t enough to mine the depths of the latent, wild adventure by which every stone in the state is cobbled together. Nonetheless, one free day in New Mexico on the continuum of forever is better than none. A few of us decided to follow somebody’s advice and drive the High Road from Santa Fe, up through the jagged landscape into the Sangre de Cristos to Taos Pueblo.

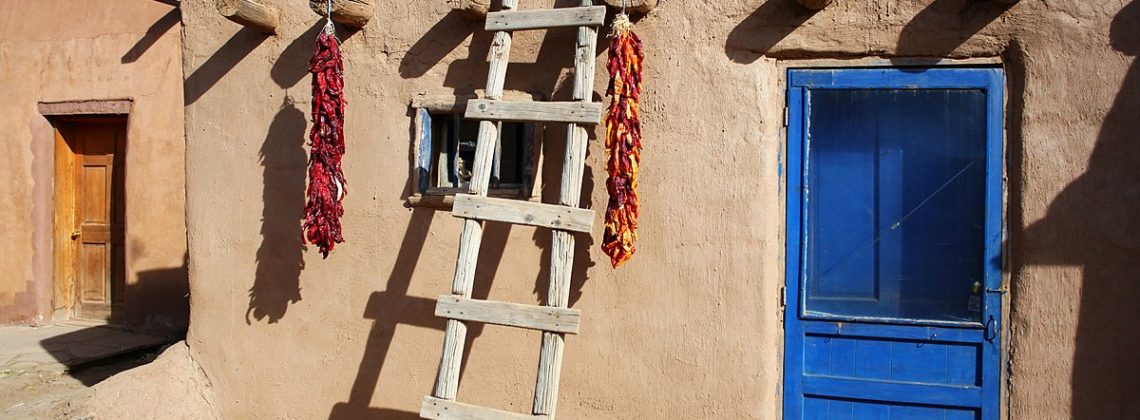

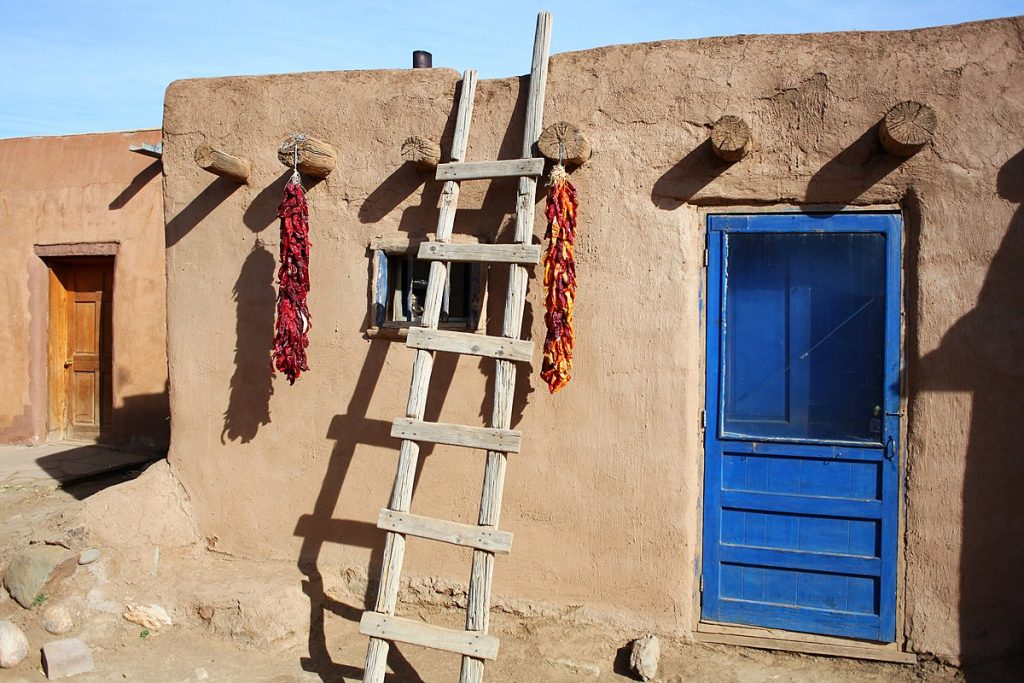

I barely knew about Taos Pueblo, and that only from Ansel Adams’ photographs. Boxy, adobe habitations with versatile roofs and ladders like vertical sidewalks. All backdropped by a particularly ancient sky that God tacked to the universe with the silver-headed roofing nail we usually call the moon. The moon is common, but in the Southwestern sky it invites veneration. All that reflects its reflected light seems to radiate holiness.

People live in Taos Pueblo. It is one of the relatively few UNESCO World Heritage sites in the United States. Puebloan Native Americans, called the Red Willow People, have lived there since long before conquistadors booted the land in the name of God, and they live there now. Not in quasi-historic mock-up tableaus that George Saunders would skewer. Real people in real homes, with their families, where they eat and argue and love and curse and sleep. There, they get bored. There, they have ideas. There, they decide what to make for dinner every night. The busloads of tourist-types, like my pals and me, show up in what I can best describe as the only waves that arid landscape will ever see.

Unmissable in Taos Pueblo is the signage prohibiting the tourist-types from the off-limits areas of the community. One of these collective areas includes the ladders by which residents can climb to the usable roofs of their homes. The signs preventing anybody but residents from ladder climbing—again, all over Taos Pueblo—read something like: DO NOT CLIMB THE LADDERS. There are no lawns, driveways, nor any other pieces of “home” recognizable to Euro-descendant Americans that differentiate, simply via social norms, these reserved parts of the community. The signs are both a courtesy and a necessity.

At the end of our visit a commotion broke out across a courtyard. A tourist-type, a white man, evident less by the color of his skin than by the gall of his white-ish behavior, had begun to climb one of the ladders and he climbed like he was the only person in the world who knew what ladders were. He climbed like the ladder he was climbing hadn’t been ascended and descended in the centuries that had come and gone before he was born. He climbed like a Bar-Adam, this phony first man on the land of real first people. He climbed like an Antichrist who’d been called home to an exclusive heaven. The residents and, thankfully, a number of the other tourist-types, hollered at him to come down. But he didn’t. Wouldn’t.

For our part, my friends and I toed the gravel and called him an evil bastard and a gutless piece of shit.

And all this would be a succinct exemplification of the still-extant maltreatment running from white America to Native Americans. But, about half an hour before we saw the man climb the ladder, my friends and I had found ourselves in a corner of Taos Pueblo with a high fence through which we could not see. Like the ladders, whatever was beyond it was off limits to anybody but the residents of Taos Pueblo. If I recall correctly, it was an area for religious practices, but even if that weren’t the case, even if it was just a junk piece of land whose only purpose was to exist without me, they’d told me I couldn’t see it.

They’d told me I couldn’t see it. A wrath leapt in my chest, up my windpipe, high as my eye teeth. A bleak reaction that appeared in my heart and then disappeared, all in about a quarter of a second. But in that pinned instant: I can’t see it? I can’t have it? Yes I can yes I can yes I can yes I can see anything I want to see and I can have it too and I can have anything and I can have everything and I can have your land behind this fence and I will take it and it will be mine and I will kill you and I will possess the land and I will lord over what once belonged to you like a king on a throne made of skulls.

It’s the instinct that propels every evil act, from the innocuous to the cataclysmic, the genesis of all evil and the justification of all evil, which is itself a great evil, and, good God, it’s inside me. I slunk from the fence with my friends like nothing had happened, and then expressed my sincere disgust for the man on the ladder like he and I had nothing in common, and now, years on, I wonder about the eternal ramifications for the God who nailed the moon to the sky, and for the god of destruction sitting at his keyboard right now, writing this.

Paul Luikart is the author of the short story collections Animal Heart (Hyperborea Publishing, 2016), Brief Instructions (Ghostbird Press, 2017), Metropolia (Ghostbird Press, 2021) and The Museum of Heartache (Pski’s Porch Publishing, 2021.) He serves as an adjunct professor of fiction writing at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia and lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee.