Suspicion of a text is easy. Trusting is hard.

Art in Doubt: Tolstoy, Nabokov, and the Problem of Other Minds by Tatyana Gershkovich. Northwestern University Press, 2022. 240 pp., $32.

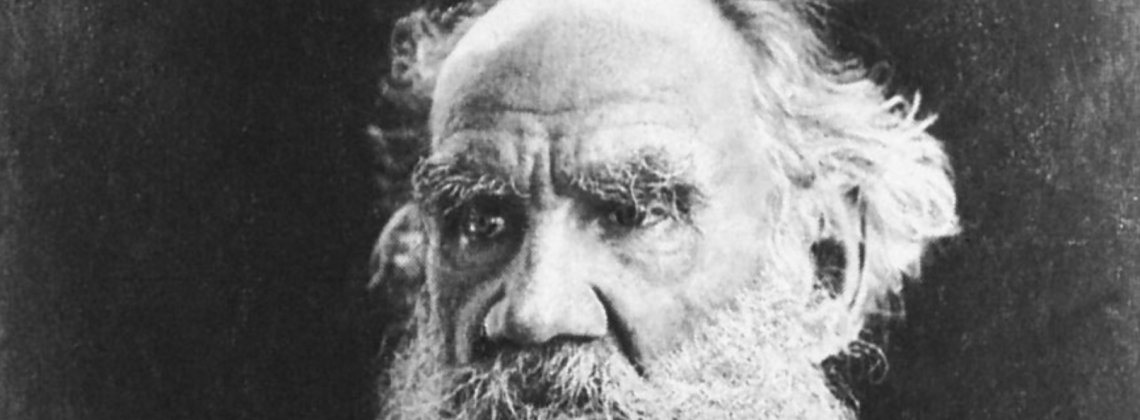

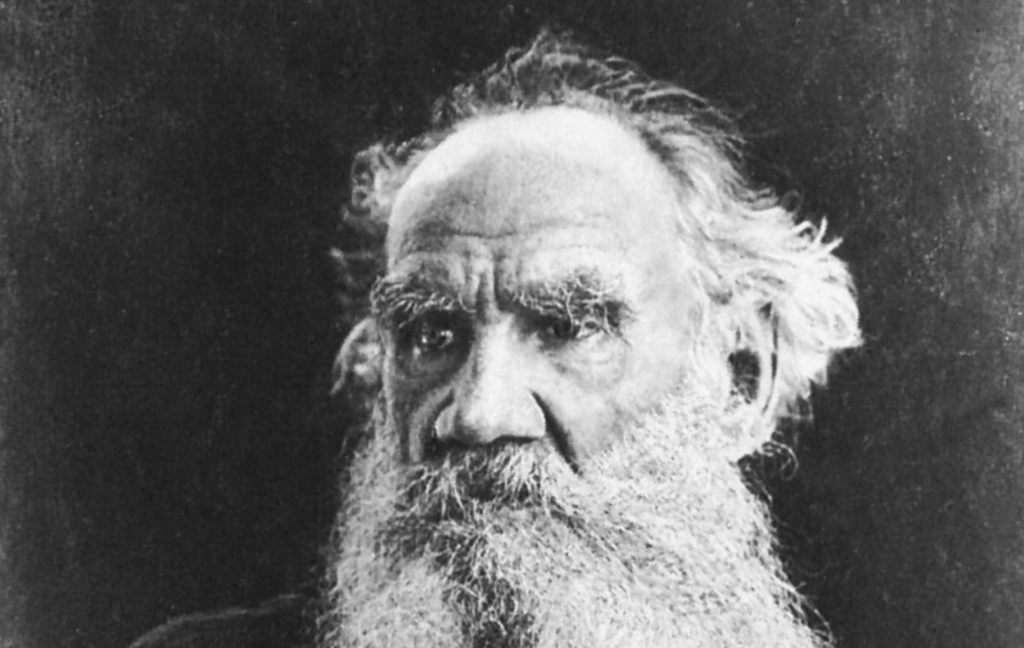

One of my first exposures to the integration of faith and wisdom was through Philip Yancey’s Soul Survivor. In a chapter on the great Russian novelists Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy, Yancey surveys their influence on the big philosophical and theological questions of the past century. Novelists like Tolstoy—or, later on, Kafka and Beckett—offered probing narratives that in turn have equipped philosophers to communicate their own ideas.

Gershkovich’s aim in this book is to consider the role of literature in the shadow of the philosophical school of suspicion—with Marx, Nietzsche and Freud as the poster children. Part of the Studies in Russian Literature and Theory series at Northwestern University Press, the book builds on the author’s dissertation “Held Captive: Tolstoy, Nabokov, and the Aesthetics of Constraint.” She ranges over modern Russian and American literature and theory, with special focus on the writings of Tolstoy and Nabokov (yes, the Nabokov of Lolita fame, even though there is not much about that book in this study).

At the heart of this volume is a consideration of two styles of literature: in the author’s terms, “Tolstoy’s simplicity, Nabokov’s complexity.” Gershkovich asks the same sort of questions of both. Can the author’s message be communicated to the reader? Does one’s consciousness speak to another’s?

Although scholars see Tolstoy and Nabokov as part of the modern philosophical tradition of skepticism that began with Descartes’ radical doubt, the very fact that they write at all illustrates their desire to be read and comprehended. Both consider skepticism a real problem, but each in his own way thinks that his literary art can overcome it. Gershkovich writes that “Tolstoy and Nabokov help us see that approaching the text with suspicion is easy; trusting it is hard.” This is an important message in our time, when mass information is at the tip of our fingertips yet misinformation runs rampant.

A reader with previous background in Tolstoy’s and Nabokov’s novels and short stories might be best prepared for reading this book. However, after reading Gershkovich’s focused analysis of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina or Nabokov’s The Gift, even a reader without significant previous experience with these writers may be inspired to finally tackle these novels.

For instance, discussions of art and beauty—and aesthetics in general—are present in the descriptions of multiple characters in Anna Karenina. It is Anna’s stunning physical beauty that Tolstoy seems to insist will grab everyone’s attention. He bypasses aesthetic theory to simply frame Anna’s beauty as something that is empirically evident to all, establishing that there are just some things or people that are universally beautiful.

As for Nabokov, the quintessential literary artist: He does not merely take issue with the lazy general reader or take offense at someone who sees literature as sheer entertainment—he is also alarmed by the reader who uses literature merely as a means for studying history or politics. In fact, he is more concerned about the experts who still cannot comprehend him, no matter what theoretical lens they apply, than about the lazy reader. But for all of his unease about his readers, the mere fact of his concern still illustrates Nabokov’s insistence that someone out there in the world can comprehend him.

The works of Tolstoy and Nabokov continue to entice the bibliophile. Reading their works today in our own world of ubiquitous media technology suggests the contribution the bibliophile might make to our growing post-literary society. Absorbing books slowly and carefully in order to listen to another person—a gaze focused on their words—is just what our society of speedy mass information and constant distraction needs. Books, especially long books, offer us a chance to take our time to slowly climb the literary mountain, page after page, intentionally receptive to what the author is trying to communicate to us.

Even the older Tolstoy took the time to painstakingly collect words of wisdom from the great books of history for his compilation Circle of Reading. One wonders why. On the one hand, what better way is there to be seized by words than through the sayings of religious, political and literary giants? On the other hand, these pearls seem as artificial as the sayings on an inspirational calendar. And maybe that is the point. For some readers, it takes a daily inspirational message to make them receptive to a voice that is not their own. In Gershkovich’s narrative, Tolstoy the artist, selecting and recording the sayings, joins Tolstoy the reader, waiting to be moved by these same words.

One of the highlights of the book is the examination of Tolstoy’s novella The Kreutzer Sonata, whose “killer-philosophizer” narrator later reappears as Nabokov’s “suffering individual” in his unpublished “Pozdnyshev’s Address.” In both cases the narrator’s egoism is under criticism, illustrating “the idea that brutality is born of unrelenting self-absorption fortified by distrust.”

There is a form of cruelty in self-contained subjectivity—especially of the hyper-skeptical type. The refusal to hear from another is a form of narcissism. Perhaps as critical thinkers we tend to promote doubt so much that even basic examples of trust come across as naïve. With so many options to grab our attention, we have forgotten how to intentionally trust.

In fact, the philosophical insights I gained from reading Gershkovich make me recall the reaction I’ve recently had to reading Karl Ove Knausgaard. Knausgaard has the audacity to be transparent to himself and the reader—dismissing, for instance, Marx, Nietzsche and Freud—the master trio at the core of the hermeneutics of suspicion—and their postmodern children with a wave of a hand. I find this audacity refreshing.

In their own way, Tolstoy and Nabokov narrate stories that attempt to produce empathy. They do this sometimes by having their characters learn from their experiences of encountering others. At other times their subject fails to gain empathy, so it is up to the reader to learn from this experience. Empathy answers the question, Why do we read? Many of us read so we can intentionally listen to someone other than ourselves. It is not the only reason for literature, but it should be significant.

And yet, in her book How to Read Now, Elaine Castillo points out that the manufacturing of the empathy machine for literature is often reserved only for some books. She asks stirring questions. Why are some books merely for universal aesthetic tastes while others are meant for the reader to learn something new about oneself and the marginalized Other? What does it mean for me as a reader that I need a work of fiction to awaken empathy within myself?

What is helpful in Gershkovich’s study is that she has taken two writers usually canonized as part of a universal literary aesthetic Mt. Rushmore and demonstrated that no matter how profound or simple the artists, the basic point is that they want to be read. Even Tolstoy and Nabokov, who wrestled with the elitist ideal of true literary art, agonized over simply being read. Making the case for readability, Gershkovich concludes that there is nothing more depressing than the lonely skeptical reader. Having a critical eye is fine—but not at the cost of segregating oneself on a literary island, marooned with one’s own thoughts.

Michael Jimenez is associate professor of history at Vanguard University. He is the author of Remembering Lived Lives: A Historiography from the Underside of Modernity (Cascade Books, 2017). He is currently researching the influence of Cesar Chavez’s nonviolent activism and the recent history of Costa Rica.