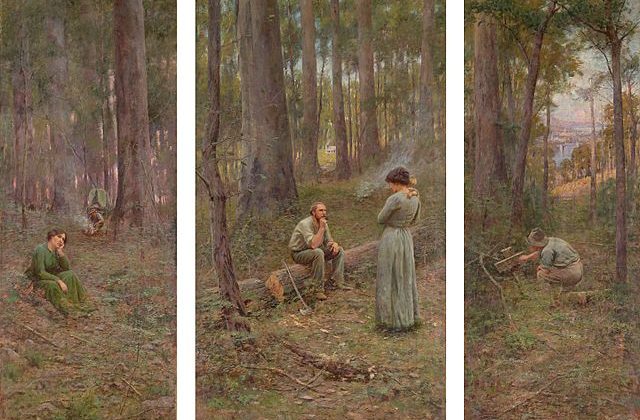

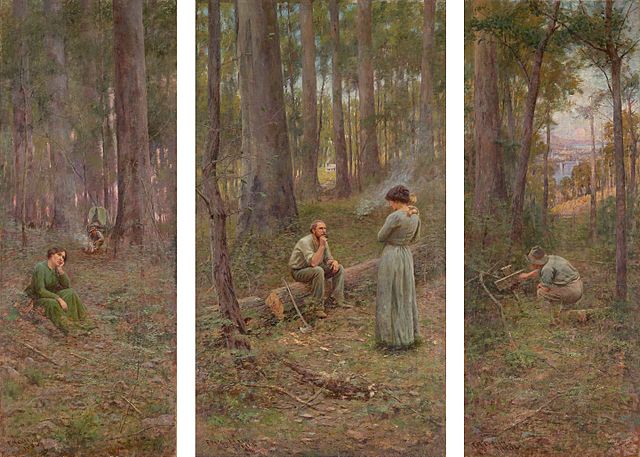

Marriage roles are hotly contested in our society. Wrapped up as they are not just in the deeply important work of the family but also in debates over conceptions of biological sex itself, these roles are difficult to define. Efforts to attach inflexible “shoulds” to being a husband or wife often prove inadequate when applied to two real people, and yet there are natural and cultural reasons that do place real limits on the division of labor. Which parts of our cultural expectations about womanhood and manhood in marriage are and ought to be flexible, and which are not? How do we divide the work of family life in ways that are practical but also fitted to the particularities of a particular couple?

As a historian, I am particularly interested in thinking about how our concepts of “traditional” roles match up against what we actually know about American marriage over time, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries. Lately, I have been enjoying exploring this question in part through a handful of books (mostly fiction) by the mid-century American author Janice Holt Giles. Giles’s characters speak to the complicated question of how womanhood, manhood, and division of labor actually played out in marriages over time. These are books that paint realistic pictures of how unique personalities and contexts affect marriage without denying the biological and social differences between men and women.

Take Giles’s masterpiece,Hannah Fowler, for starters. After the title character travels over the mountains to Kentucky during the Revolutionary War, she quickly enters into a marriage of convenience that is also one of unexpected attraction.

Hannah Fowler is tall, physically strong, and homely. She was raised by her widowed father and likes to hunt and track, though she also cooks and sews. When Hannah’s husband is gone for a few days and she’s done all the housework and tended the baby and put the supper on, for example, she figures she might as well make some ax handles out of the spare hickory logs in the yard. She hasn’t got anything else to do, and she enjoys it, and is good at it, too. And when the baby cries in her cradle while Hannah prepares to go the barn, Hannah tells her to holler away if she feels like it: Mama simply must go feed the stock.

What a relief that would be for a modern mother, who is so often beset by shame and impossible expectations on all sides! To not feel that you have to somehow find a way to safely carry the baby through the figurative snowstorm to the figurative barn and then also somehow keep her safe and happy there while you work with the figurative dangerous pitchfork and animals?

We modern mothers who complain of not even getting to go to the bathroom alone clearly have a thing or two to learn from Hannah Fowler, who cares for her baby tenderly but does not agonize over doing what must be done. Furthermore, we see from Hannah that if a woman needs to make ax handles in order for her family to have them, then, by golly, that is a womanly thing to do.

The tradition of helping one another is deeper than the tradition of separating tasks by sex.

Following Hannah Fowler, Giles went on to write about Hannah’s descendants in several more books. The fourth of the series is The Believers, a strikingly unique story about a married couple who, by the husband’s choice alone, join the Shakers.

They join the Shakers. How could this book no be fascinating? The tale follows Rebecca (Fowler) and Richard Cooper’s from their early, mostly happy marriage through to the sex-separated lives they must live when in the Shaker community, and finally to their heart-wrenching struggle over what each owes the other in marriage. At the center of the story is Rebecca’s dilemma over whether or not to make her final promise to the Shakers, which she does not wish to do but without which her fanatical husband cannot make his own. Unsurprisingly, given this, possession of other human beings is also a theme, with a sometimes simplistic and uncomfortable side story about how the couple manages their slaves.

If you are interested in reading more about hardship in marriage, especially between mismatched partners, I would also recommend Giles’s unexpectedly dark novel The Plum Thicket, in which a grandmother’s interior repressions and mental illness and a grandfather’s lack of responsibility end in tragedy. I am still pondering the mysteries of this marriage weeks after my first reading of the book, but I don’t want to give too much away here.

Yet while Giles recognizes the hardship that can accompany even a generally happy marriage, she is also a master of humor when discussing married life. Her description of one of the early years of her marriage to Henry Giles in 40 Acres and No Mule exposes the steep learning curve that new spouses face, but it also shows a deep appreciation of living and working together as a couple and seperately in their own spheres. I have never read a funnier book than this story of the marriage of two writers making do on a hardscrabble Appalachian tobacco farm. It’s like Betty MacDonald’s The Egg and I of Ma and Pa Kettle fame, only even better.

The four Giles works I mention here deserve to be on every thoughtful reader’s shelf, especially if he or she is interested in contemplating the many facets of American marriage and family life. Still, I can’t say that I love everything Giles has written. In particular, Giles’s racial sensibilities, though common to her time and background, represent an inaccurate point of view of enslaved people that endorse infuriating and damaging myths. They are, however, historically interesting and remind us of how different racial common sense was even in the mid-twentieth century. Some Christian readers will also disagree with Giles’s conclusions on divorce in some of her books, although all will nevertheless sympathize with the difficulties of the cases she puts forward.

But the point here is that these very different marriages, while honoring certain biological realities and cultural traditions, also offer examples of how circumstance, context, and personality also affect marriage roles. Hannah Fowler is feminine even though she is rough in her ways. She is also confident in her motherhood and in the goal she shares with her husband of putting helping their family first, even if that means sometimes adjusting their roles. Rebecca Cooper believes that she has a duty to her husband and yet also recognizes her own primary spiritual duties, even when they are in conflict with his. The Plum Thicket shows what goes wrong when spouses are insufficient unto each other, and 40 Acres guffaws at some very typical male-female interactions while also showing the power of marital unity in supporting the dreams of each spouse.

So perhaps there is more to learn about marriage from the American past (and its literature) than initially meets the eye. We may, of course, look at American marriage mores before 1963 or so and think glibly either, Aha! Oppression! Or, Aha! Perfection! But then we would miss out on learning that marriage is first and foremost comprised of people in relationship. and that each such relationship will always differ at least in some small way from every other. We are men and women in marriage, yes; but our marriage roles are there not to divide or oppose us, but to unite us in support for each other.

Or at least, so suggests Janice Holt Giles; and I am inclined to agree with her.