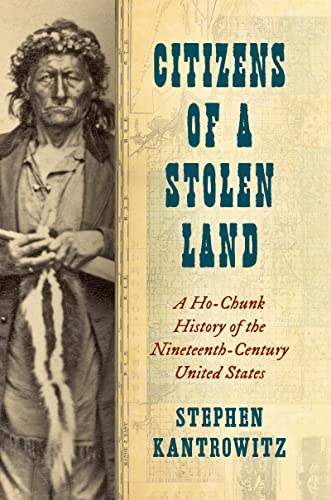

Stephen Kantrowitz is Plaenert-Bascom and Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This interview is based on his new book, Citizens of a Stolen Land: A Ho-Chunk History of the Nineteenth-Century United States (University of North Carolina Press, 2023).

JF: What led you to write Citizens of a Stolen Land?

SK: I wrote Citizens of a Stolen Land because, even though I have a Ph.D. in 19th-century American history and have taught in Wisconsin since 1995, I had lived here for fifteen years before I really thought about the fact that every square foot of my adopted city—like every square foot of the continent!—was, not very long ago, someone else’s homeland. Since that lightbulb went off, I have been turning my attention to who lived here, how this place became part of the United States, and what happened to the people who lived here.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Citizens of a Stolen Land?

SK: Citizens of a Stolen Land brings together two stories we normally tell separately: the crisis of the United States during the Civil War era, and the actions of Native people and Native nations during that era. It does this by exploring how one group of Native people—the Ho-Chunk—encountered the American idea and policy “citizenship,” deduced the threat it posed to their integrity and autonomy as a people, and finally turned it to their advantage as a way to remain in their ancestral homeland despite laws and policies that demanded their exile.

JF: Why do we need to read Citizens of a Stolen Land?

SK: Citizens of a Stolen Land asks readers to reconsider the relationship between Native American history and U.S. history, and to think about the ways that citizenship, an idea we are used to thinking of in egalitarian, aspirational, and heroic terms, could also be a coercive and destructive force.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

SK: I became an American historian in college, when I began to see that the questions I was most interested in—especially the ways racism has structured American political and social life—could only be answered by closely examining the past. I was lucky to have inspiring teachers—lecturers like Edmund Morgan and David Montgomery, and discussion leaders like Susan Johnson—whose example made graduate school seem like a good idea.

JF: What is your next project?

SK: I’m still exhaling from this book, but at the moment I’m very interested in what happens when people have the “lightbulb moment” I describe above, and begin to explore the Native past and present of the place they call home. I plan to do some further research and writing about the two places I have called home—Madison, Wisconsin and Brookline, Massachusetts—while teaching a research seminar for undergraduates that explores the sources and methods available for such histories.

JF: Thanks, Stephen!