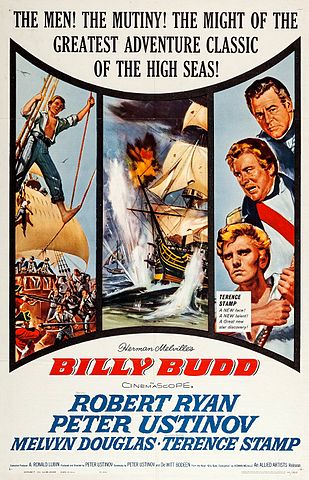

Billy Budd is one of Herman Melville’s most enigmatic writings. It involves an inexplicable animosity toward a handsome sailor, an accidental death, and a verdict of ambiguous justness. The captain of the ship on which the events take place is “Starry” Vere. In the story, we learn several things about him, including his taste in books:

“He had a marked leaning toward everything intellectual. He loved books, never going to sea without a newly replenished library, compact but of the best. The isolated leisure, in some cases so wearisome, falling at intervals to commanders even during a war-cruise, never was tedious to Captain Vere. With nothing of that literary taste which less heeds the thing conveyed than the vehicle, his bias was toward those books to which every serious mind of superior order, occupying any active post of authority in the world, naturally inclines; books treating of actual men and events, no matter of what era—history, biography, and unconventional writers who, free from cant and convention, like Montaigne, honestly, and in the spirit of common sense, philosophise upon realities.”

In our own moment, reading is, fortunately, considered somewhat popular. However, many of the most popular books are somewhat “light” reads. They are not necessarily challenging. In other arenas, such as fitness, we are encouraged to push our limits. With regard to life, Steve Magness has a good, recent book called Do Hard Things. In Billy Budd, Captain Vere might be considered an argument for reading the hard things. Serious books for serious people. Something that cannot be consumed on a cross-country flight.

The point is not to shame anyone for their reading choices or to limit them to “classics,” but to encourage us all to expand our palettes. The things we read provide us with narrative resources for whatever we face in life. Hard times can sometimes be made easier with harder books.

One of the remarkable things about the British experience of the Great War is what the men were reading in the trenches. Yes, men read magazines and the penny press, but they also read all kinds of literary classics. Young officers, especially, comforted themselves with poetry and literature. In Some Desperate Glory, Edwin Campion Vaughan makes frequent reference to his copy of Palgrave’s Treasury, which he took everywhere. Siegfried Sassoon was happy to have Thomas Hardy on hand. Many men also wrote poetry and memoirs during the war.

You might think that the harshest conditions would create a desire for the lightest literature, but it isn’t always so. In The Worst Journey in the World, Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s account of the failed Robert Falcon Scott South Pole expedition, he recounts the importance of poetry and literature, referencing the books that he and others used and treasured. “Bleak House was the most successful book I ever took away sledging, though a volume of poetry was useful, because it gave one something to learn by heart and repeat during the blank hours of the daily march, when the idle mind is all too apt to think of food in times of hunger, or possibly of purely imaginary grievances, which may become distorted into real foundations of discord under the abnormal strain of living for months in the unrelieved company of three other men.” Yes, apparently—in a hut at the South Pole, living on seal meat, caring for dying mules, sitting through months of darkness, or sledging in freezing temperatures—poetry is useful.

Reading great books will not automatically make us great people in trying circumstances. In Billy Budd, Captain Vere becomes seemingly irrational when confronted with Claggart’s accidental death. The surgeon wonders if Vere has been “suddenly affected in his mind.” Vere hurries along a trial, which could have been done by the admiralty, and pressures the jury to accept a verdict he decided before they convened. It is beyond the scope of this essay to resolve the psychological drama of Billy Budd, but hopefully it can point out that it is precisely such complicated texts which can be an aid to us when we are in complicated situations.

Easy reading can be a genuine comfort. Cherry-Garrard concedes that when preparing for sleep in Winter Quarters, you may want a book which will “take you into the frivolous fripperies of modern social life which you may not know and may never wish to know, but which it is often pleasant to read about, and never so much so as when its charms are so remote as to be entirely tantalizing.” But easy reading is unlikely to aid us in processing uneasy times. If we have only a few plots and shallow characters to draw from, we will be poorer for it. What phrases will come to mind in a situation? What examples will we have to draw from? What possibilities can we envision for moving the plot forward?

When sledging, the hardest part of the journey at the South Pole, Cherry-Garrard did not want frivolous fripperies. “Most of us managed to find room in our personal gear when sledging for some book which did not weigh much and yet would last.” What kind of book? He recommends “one which will offer a wide field of thought and discussion.” It is worth it to read hard things, because we will face hard times. When we are in the thick of it, complex characters and plots and challenging ideas will be good mental company. As we sledge through life, let’s sometimes read like Starry Vere.