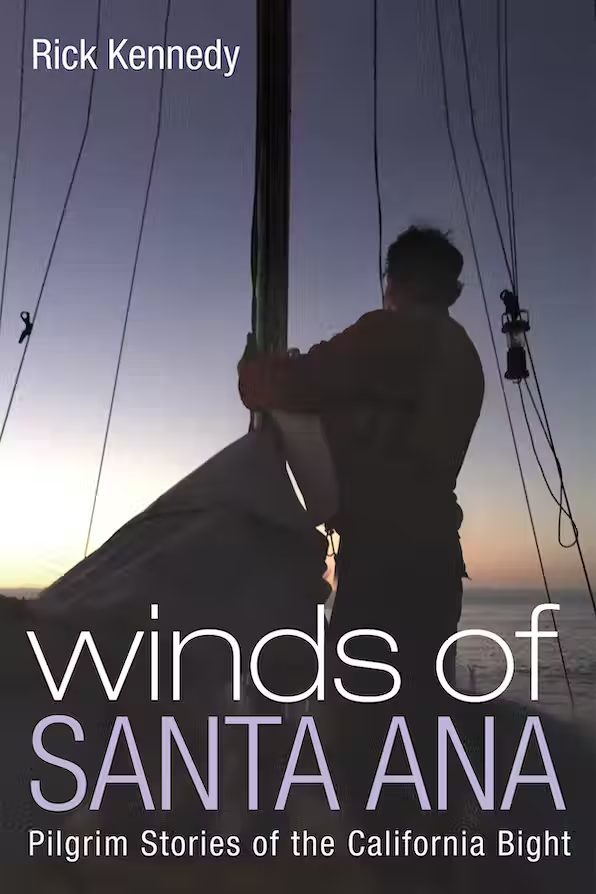

Winds of Santa Ana: Pilgrim Stories of the California Bight by Rick Kennedy. Wipf and Stock, 2022. 206 pp., $25.00.

It is a time-tested truism of the academic profession that the best adventuring is of the armchair variety. But every now and then, some of this tweed-wearing tribe do break the mold. One particularly well-known example is the Norwegian ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl. An academic by training, Heyerdahl was not your usual college professor. Fascinated with the idea of mobility of ancient civilizations across the globe, he tested his theories in action, resorting to what we might term today experimental archaeology.

In the Kon-Tiki experiment, he set out to prove that the inhabitants of Polynesia had arrived there originally on basalt tree rafts from South America. And so, together with a crew of five other like-minded adventurers, he constructed a raft using what he believed, based on his research, were the most authentic materials and technologies possible, and successfully made the voyage that he had theorized was possible.

Scientists today take issue with Heyerdahl’s theory of Polynesian origins in South America. And yet, both the Kon-Tiki expedition and the subsequent Ra expeditions, in which Heyerdahl undertook a trans-Atlantic voyage in a papyrus reed boat, modeled on those depicted in Egyptian pyramids, showed the intriguing possibility of much greater degree of seafaring mobility of ancient peoples than generally theorized. Technological snobs that we moderns are, after all, it is difficult to believe that people could cross an ocean on, well, a raft.

Still, just because Heyerdahl proved that this was possible doesn’t mean that it actually happened. Scientific findings aside, Heyerdahl’s accounts reveal his love of much more than just science and the desire to prove his theories true. He was, first and foremost, a man who loved the sea, sailing, and everything about the adventure of it all.

Heyerdal’s spirit of seafaring adventuring came to mind while reading Rick Kennedy’s truly fun recent book, Winds of Santa Ana: Pilgrim Stories of the California Bight. Like Heyerdahl, Kennedy is a life-long adventurer with a passion for both history and sailing. But their similarities, perhaps, end there. Unlike Heyerdahl, who was eager to traverse the globe on his experimental creations, Kennedy has spent almost his entire lifetime sailing one area—the California Bight.

This book is an attempt to take all of these experiences of a lifetime and bottle them up in book form. Highly readable yet well-researched, it is a sort of journal documenting Kennedy’s reflections—historical, spiritual and theological, and personal—of these decades of voyages in the region and his concomitant intellectual voyages of reading widely across world history and the history of modern evangelicalism. The result is a beautiful love letter to the region he calls home. But this love letter still sees the historical flaws and shortcomings that the region has witnessed, all while celebrating the Bight’s glories, both natural and man-made.

The timing of the book in this stage of Kennedy’s career is not accidental, in fact. It really is the sort of book that one could only write after decades of deep reflection and prayer about the topics involved. As Kennedy himself notes about the project: “For many years I have been a pilgrim on this pilgrim coast. I think of myself as created, in part, by the California Bight. I have long taught the history of this place at one of its little colleges. I am nearing retirement and need to assess what this place has made of me and gather together what I think this place says about itself.” He adds, further connecting the themes of travel and pilgrimage, both on the water and within one’s mind: “Pilgrims, as I understand the role, are not explorers. Pilgrims are not cynics. Pilgrims go where others before them have gone and believe what others before them have believed.”

For Kennedy, just as it was for his intellectual role models, such as Augustine and Boethius, history and theology are inseparable. Furthermore, Kennedy sees history and theology in concert with nature in the very process of sailing the California Bight. He poetically notes in opening the book, “It is hard to be an atheist here. Notions of purposelessness have to struggle to survive in a place so beautiful. The California Bight is distinctly revelatory, sacramental, and hopeful.”

Sailing, Kennedy is convinced, a spiritual practice. A life-long intellectual and historian, every action for him is also one of continuous historical reflection and discovery. In particular, both sailing and historical reflection are acts of spiritual pilgrimage. This is important in cultivating the virtue that sailing perhaps teaches more than others: humility. After all, one is never truly in full control when sailing. This humility, of course, is also essential for historians, who are sometimes fooled inadvertently into thinking that they are in greater control of their intellectual journey than they really are.

Over the course of the book, Kennedy takes the reader along on sailing voyages to all nooks and crannies of the Bight on the Boethius, his long-time boat. And just like the original Boethius, Kennedy imagines that Philosophia, the spirit of philosophy, joins them on these voyages, offering her own reflections and words of wisdom. Her presence reminds an important truth. For a lover of books and the spiritual world, solitude does not mean the same thing that it does to other people. A thinker, especially one who is a historian, is never truly alone.

In the process of documenting these voyages, Kennedy brings up important methodological questions about how Christian historians should approach their craft. Can the reading and writing of history be a spiritual practice? Many early Christian thinkers clearly thought so. But in our modern post-Enlightenment sophistication, we try so hard at times to distance ourselves from such, well, unsophisticated attitude. The modern historical profession, after all, is firmly unspiritual—and often rather un-inspiring—in scope.

And so, Kennedy’s modeling of spiritual, geographical, and historical pilgrimage in this book as inextricably connected is a valuable reminder that as Christian thinkers, we are not just bodies. Nor are we just walking brains. As embodied believers and thinkers, we live in the here-and-now, with all the attendant historical implications of this reality, including the need for repentance for historic sins of our forebears. But as Christians, we also have the assurance that this world is not all that there is. Connecting these themes, Kennedy appropriately closes the book with one of the prayers that Boethius’ Philosophia offered a millennium and a half ago:

“What brings all things to order,

Governing earth and sea and sky,

Is love…

O happy race of men,

If the love that rules the stars

May also rule your hearts.”

I initially ignored this because I’m a Midwesterner with no interest in sailing. I admire the work of both Kennedy and Williams, however, so eventually I did decide to read it. I was so enchanted I’m now ordering the book.