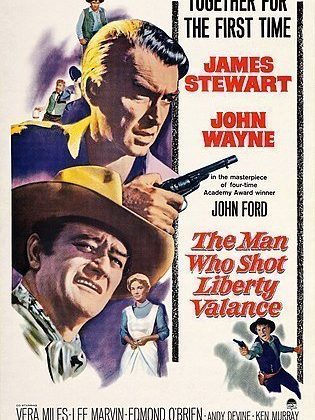

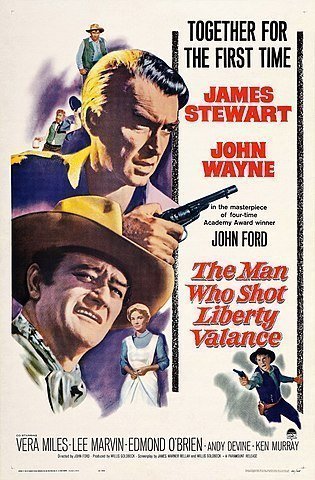

A mark of a truly great work of art is the ability to go back time and again to the work and still find something new. As a homeschooling father I recently took command of my children’s education and introduced them to a great work of art—John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. I am among those who think that Liberty Valance is the quintessential Western, the finest rendition of that classic film genre.

Liberty Valance is great in part due to casting. It features, of course, the Michelangelo’s David of Western stars, John Wayne, as well as perhaps the twentieth century’s greatest male actor, James Stewart. Both excel in bringing to life their character’s central feature. In Wayne’s case, it is the (dare I say it) true grit and toughness of Tom Doniphon. For Stewart, it is the naïve earnestness of lawyer Ransom Stoddard. Lee Marvin’s turn as the eponymous Liberty Valance is a masterclass in his portrayal of a violent, vicious, cruel criminal and hired gun. The tough but tender Haley is prevented from being a female caricature by a feisty Vera Miles. Andy Devine as the buffoonish sheriff Link Appleyard and Edmund O’Brien’s portrayal of the eloquent drunk, Dutton Peabody, proprietor of the Shinbone Star newspaper, provide needed comic relief without becoming clowns.

Westerns have a fairly consistent story line. There is a hero, proficient in violence. He has a counterpart in a villain. Both of them reside outside of town. There is a town full of common citizens trying to build civilizations. For one reason or another, the villain and his cohorts oppose civilization. They are willing to use their proficiency in violence to run off the townspeople or small farmers, who are not skilled in violent gunplay. Along comes the hero. Matching the villain’s proficiency, he is able to apply the violence necessary to save civilization. He defeats the villain only to “ride off into the sunset.” Neither the hero nor the villain, remnants of a more violent, less civilized era, are fit for modern enlightened life. His job complete, making the town safe for shops, schools (and schoolmarms), and churches, the hero leaves the stage a tragic figure, the instrument of his own obsolescence.

One sees these themes quite consciously depicted in films such as My Darling Clementine, Shane, and The Searchers. But nowhere, I believe, are these archetypes so obviously and skillfully deployed than in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

We first encounter Liberty outside of town. He appears to have no home, making a living as a thief and as a hired gun of the large cattle interests. Doniphon also lives outside of town, running his own cattle and horse operation. It is Stoddard, an early victim of Liberty’s violence, who resides in town. He is not only a lawyer, a man of law and education, but he also starts a school. In this sense, Stoddard’s lack of proficiency in violence, comically demonstrated and mocked by Doniphon, is heightened by having him taking on the traditional female role of school teacher. To add to this characterization, he also does dishes at the boarding house restaurant to earn his room and board.

It is the underlying plot of the film to which I want to direct our attention. In classic Western storytelling, the basic conflict of the film is the fact that the unnamed territory in which the people reside (Arizona?) is aiming for statehood. The large cattle interests are resisting statehood, as they know it will mean law and order, as well as railroads and towns, ending their dominance over territorial life. The townspeople, for just these reasons, support statehood. One of Liberty Valance’s jobs is to use violence to frighten the townspeople into refraining from pushing for statehood.

Here is the new theme I found on this most recent viewing of Liberty Valance. The film makes a strong defense of what mid-19th century advocates would have called free labor ideology. Drawing from an editorial by newsman Peabody, Stoddard tells his school children that statehood will promote the interests of small homesteaders and “small shopkeepers” against large cattle interests. (You can watch this scene here).

Similarly, near the film’s end, at the convention to elect a territorial delegate to Washington, the debate is between cattlemen and townsfolk. Peabody, speaking for the townsfolk and for the nomination of Stoddard, says, “The cattlemen seized the wide open range for their own personal domain and their law was the law of the hired gun.” But their time has passed. Now is the age of railroads, bringing people, “steady, hardworking citizens.” These are “the homesteader, the shopkeeper, the builder of cities.”

We can illustrate this mindset in American history through the thought of Abraham Lincoln. Most directly in a speech in Wisconsin in 1859, Lincoln defended the concept of free labor. To do so he distinguished free labor from slave and wage labor. Slave labor, of course, is unjust. But Lincoln also sees wage labor as a deficient condition for a worker. While wage labor is not wicked, as is slave labor, it should not be a permanent condition. There is something in hired labor that partakes of dependence.

Lincoln rejects the distinction between the owner of capital and the worker. Most laborers, he says, are in neither condition. They are neither “hirers nor hired.” What are they, then? Most people, says Lincoln, “work for themselves, on their farms, in their houses and in their shops.” Someone may start as a hired laborer, but through saving of money and learning of useful skills, he goes to work for himself. Lincoln himself illustrated this path. He held various jobs as a young man. He eventually apprenticed in the law, working under a more senior lawyer, later going on his own to run his own practice.

In his 1861 Annual Message as president, Lincoln calls this the “just, and generous, and prosperous system” that allows for the right to rise. Daniel Walker Howe argues that Lincoln’s “objective…was to defend and extend the kind of free society he had known in Springfield. This was a society of small entrepreneurs, market-oriented farmers, young men working for others until they could save enough to set up for themselves, and striving professionals like himself.”

This is the society defended by Ransom Stoddard and Dutton Peabody in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The big cattlemen are a stand-in for big business, using its power to crush smaller competitors. The rule of law exists to defend what Anti-Federalist Melancton Smith referred to as “the middling class” that forms that backbone of a free people. Lincoln opines that a society of small farmers and entrepreneurs is “independent of crowned-kings, money-kings, and land-kings.” In the battle cry of the Free Soil party, “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, Free Men.” What would Lincoln and the Free Soilers think of today’s America in which most of us labor for a wage? Are we really free? Or are we in some limbo between freedom and slavery? If we are not free laborers, what could we do to encourage a more vital free labor as defined by Lincoln?

Of course, the underlying theme of the movie is that some form of pre-civilizational violence is necessary to secure this independence and freedom. Society must retain a threat of violence to defend the peaceful, commodious life of civilization. That’s why, as the film’s last line says, “Nothing is too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance.”