In Abigail Favale’s view, our wholeness as individuals and communities is at stake

The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory by Abigail Favale. Ignatius Press, 2022. 248 pp., $16.16

More authors should emulate Abigail Favale’s approach to writing philosophy. The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory is a philosophy of sex, and sex is always interesting. But a certain type of philosophizing about it can do its darnedest to challenge that truism. Another type of philosophizing about it can just make us cringe. Favale avoids the latter pitfall by treating the topics of sexuality, the body, and gender identity with the exact level of specificity needed for her argument and no more. Her ability to avoid the former pitfall is why this book really shines: Favale takes the reader alongside as she narrates her journey of philosophical discovery in a way that reads like a story. She holds a PhD in literature, so she knows how to write. The book is compelling from the start.

Favale’s approach adds the human element that can too often go missing from theoretical expositions of sensitive topics. In conversation with both contemporary gender theorists and Catholic theologians, she seeks to articulate a meaning for our sexed human existence. Sex and gender are central to many people’s sense of personhood, but landmines abound. Favale models how to cross this field with as much care as possible while still actually getting somewhere: She clearly states her views and how she came to them, while also acknowledging where she has felt tension along the way.

Crucially, Favale narrates conversations she has had with people who disagree with her. She lets them tell their stories and make their case. She notes where she can’t entirely answer them. By listening in on these conversations, readers grasp the real-world implications of debates over the meaning of sex and gender identity, regardless of where we land. As she tells her story, Favale does not allow us to forget that the conclusions we reach affect real people—and that the ways we talk about people affect them.

Favale’s own winding journey took her from evangelical Protestant complementarianism—the belief that the Bible teaches that men lead in church and home—to evangelical feminism, to secular feminism, and ultimately to Catholicism. Fortunately, she retains sympathy for her former selves, and this attitude makes her conclusions worth reading. Unlike “anti-woke” authors, Favale continues to acknowledge great good in the contemporary feminist movement that she in part critiques.

Bracketing ordination—which she does not discuss in this book—Favale advocates egalitarianism. She wants women and men to flourish in every arena of life, and argues that discriminatory barriers remain to this flourishing, particularly for women. She does not believe men should be heads of households or sole occupiers of certain vocational spaces, or that women and men should conform to different sets of character or personality traits. Simultaneously, she believes maleness and femaleness have theological significance. Favale credits the seed of her belief in what we might call sexual difference egalitarianism to a brief encounter in college with the writings of medieval mystic Hildegard of Bingen.

To understand the theory of gender Favale proposes, we need to define some terms. In casual conversation we use the words “sex” and “gender” interchangeably to refer to male or female identity. In contemporary gender theory, however, these terms have technical meanings. To explain this distinction and its nuances, Favale takes us on a tour of the evolution of gender theory, engaging thinkers from Simone de Beauvoir to Judith Butler to Luce Irigaray. In a particularly Catholic twist, she also considers the role played by the popularization of hormonal birth control.

In brief, sex is what’s on your driver’s license. Gender, by contrast, is the expression of that identity in a particular culture or subculture. For instance, a skirt on a Scottish man means something different from a skirt on an American man. Likewise, different characteristics and abilities are valued for men and women at different times and places. Thus—although this was not the original focus of the linguistic split—in the most extreme cases you find people with a body sexed male at birth and a female gender identity, or vice versa. This is “gender dysphoria”—when one’s sense of self does not match one’s body. There are a range of potential responses to this experience. The most aggressive is sexual transition surgery. Favale calls this conceptual split between sex and gender “the gender paradigm,” and she believes it is wholly bad.

Here a Protestant complementarian might cheer, but we need to remember that, unlike Protestant complementarians, Favale does not believe that sexed bodies determine roles, careers, or personality traits. Indeed, she argues that the belief that they do is precisely what causes at least some of the psychological distress in individuals with gender dysphoria. Some people feel that they do not match the stereotypes or expectations attached to someone with their body. Rather, they match the stereotypes attached to someone with a different body.

Favale acknowledges that deep-rooted and complex cases of gender dysphoria, often apparent from childhood, exist and require sensitive psychological counseling to help the individual find a way of life that alleviates that distress. She wonders, though, if the empirically new phenomenon of widespread “rapid onset gender dysphoria” among teenagers is at least in part (and perhaps in large part) the result of the prevalence of the gender paradigm: It leads teenagers to give that name to the awkward sense of not fitting into one’s body—or simply not fitting in—that is common to that stage.

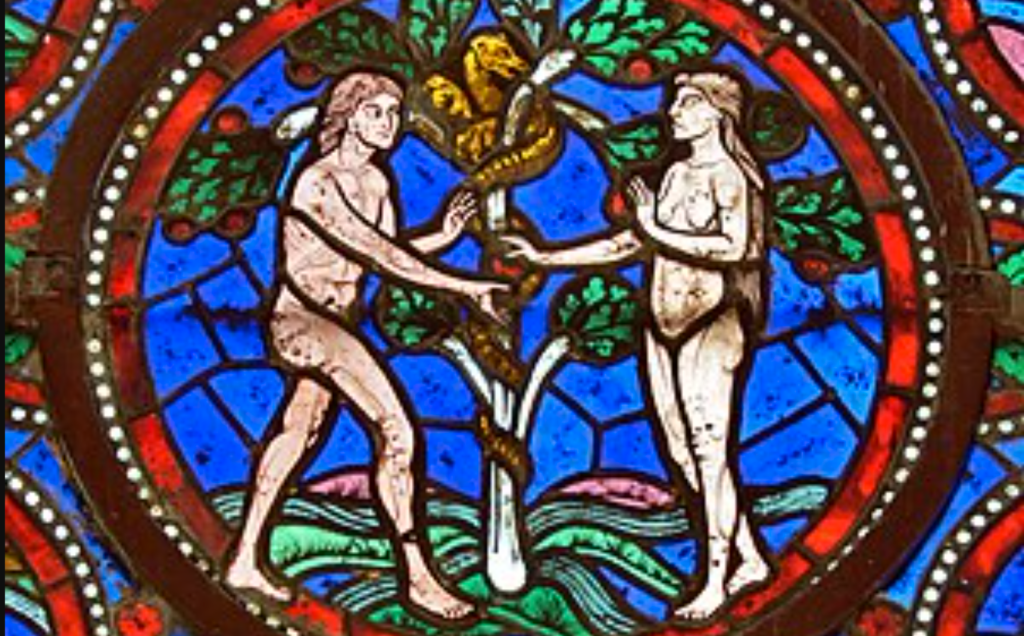

Favale draws on Catholic theology to give a reading of the significance of sexed bodies distinct from both secular gender theorists and Protestant complementarians. She argues in theological detail that in the Genesis narrative God intended men and women to bring together their combination of similarities and differences as they jointly governed creation in a partnership without hierarchy.

Sin then introduced the domination of men over women, because that’s what sin does with power. Here Favale draws on Pope John Paul II, who argued that our complementary bodies are a sign of their purpose to be given as mutual gift in marriage. Men’s greater physical power and freedom from the burdens of pregnancy and nursing mean that, as the Pontiff puts it, “the man has a special responsibility as ‘guardian of the reciprocity of the gift.’” Spider-Man and Lord Acton together sum up the fallen relationship between the sexes: With great power comes great responsibility. But power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Finally, Favale disagrees both with Protestant complementarians who see masculinity and femininity as roles or traits, and with gender theorists in the line of Judith Butler, who see them as mere performance. She argues for seeing masculinity and femininity as symbol, as Catholic sacramental theology does. Men’s and women’s respective bodies tell the story of the relationship between God and humans. As imaged by men, God transmits new life outside himself. As imaged by women, humans have the freedom of consent and can choose to actively cooperate with God in enabling new life to develop within us.

Crucially, Favale clarifies that bodies are the first, last, and only way that men and women image this reality: “Men do not have some shared capacity, skill, or accomplishment that women do not and vice versa—no, their bodies simply point toward different spiritual realities. . . . Bodily sex is not made purposeful through mandated tasks, restrictive temporal roles, or fashionable aesthetics.”

Therefore, we do not have to try to be masculine or feminine; we just are. “Masculine” and “feminine” are wonderfully diverse categories that encompass the entire range of experiences of inhabiting male or female bodies. Favale refers to this as “sex-lived-out.” Experiencing life in one type of body or the other will automatically give us unique perspectives we could have no other way, and automatically communicates the goodness of God’s design both materially and spiritually.

Favale deals carefully with the implications of these conclusions for single, infertile, or intersex individuals. For the first two groups, she contends that it is not the actual ability to generate new human life that brings meaning to the human body, but rather the mere fact that our bodies are ordered to that end. Even if particular people cannot or do not parent, their bodies symbolize the same truth.

To the vexed question of individuals labeled intersex, she notes that there has been no documented case of genuine human hermaphroditism—meaning, we know of no human who has produced both ova and sperm. We should view the rare variations from the dichotomous norm of chromosomes, genitalia, gonads, or hormones as part of the diversity within the categories of male and female.

There is something in this book for everyone to love and something for everyone to hate. The same person is fairly unlikely to agree with Favale on all of the following: hormonal birth control does violence to women; the hierarchy of men over women is wrong; butch lesbian style constitutes one of many appropriate expressions of womanhood; and intersectionality is a useful concept, but not too useful.

As I read along, points like this last one jumped out at me. I share a lot in common with Favale—we are both sacramentally-oriented Christian PhDs who advocate sexual difference egalitarianism. We have both taught about gender theories in the context of our respective disciplines, literature in her case and history in mine. We both see strengths and weaknesses in those theories. But I found myself comparatively more sympathetic, perhaps because my twenties and thirties were less spiritually tumultuous: I first encountered gender theory from a more settled place, so I simultaneously adopted and rejected portions from the get-go.

But by far Favale’s most controversial position for some readers will be her clear opposition to sex transition. Because of her sacramental theology, she believes that we are our bodies. Favale sees each person as a body-soul fusion. “We” are not our interior sense of self alone. “We” are embodied interior selves. She therefore argues that we cannot achieve wholeness through rejecting who we essentially are. Many people who identify as transgender, or who know and love a transgender person, will reject her argument.

And yet, the most moving part of the book for me was the section in which Favale has the humility to share at length the story and perspective of a transgender person she knows and loves, and who is a devout Christian. In telling the story of Addy, “who identifies as a trans-woman,” Favale uses Addy’s chosen name and avoids any pronouns at all. In this way, and by voicing Addy’s viewpoint, Favale seeks to model a way for someone with her perspective to combine integrity and love.

In Favale’s choice to avoid pronouns we have an irreducible difference for many people, precisely the type that would involve the sort of mutual forbearance that she herself demonstrates. Some of Favale’s theory of gender can be profitably adapted by people who do not share her religious outlook. For example, she discourages pigeonholing women and men into stereotypical traits but also insists that experiencing life in female or male bodies gives each sex a different, complementary vantagepoint.

But in the end Favale advocates “A Christian Theory,” as her subtitle declares. She rejects the secular postmodern assumption that material reality has no intrinsic meaning and that we therefore inscribe our own meaning on our bodies through our speech and actions. From the secular postmodern perspective, to fail to respect people’s self-naming of their own bodies is a power play—and even a form of violence, as it constitutes an attempt to impose your version of the universe on someone else. From Favale’s sacramental perspective, by contrast, bodies are “given” by God as a unit with spirits; taking part in separating them is what constitutes the violent act.

For Favale, we can only find our own wholeness and our unique contribution to the whole by receiving as gift our unique set of experiences and material realities, and by encountering God within them. Whatever our response to her theory, may we follow Favale in honoring one another’s unique and precious worth.

Andrea L. Turpin is Associate Professor of History at Baylor University and author of A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education, 1817-1917 (Cornell, 2016). She is a recipient of a 2022 Louisville Institute Sabbatical Grant for Researchers for work on a book manuscript about how Protestant women’s organizations navigated the fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the early twentieth century.