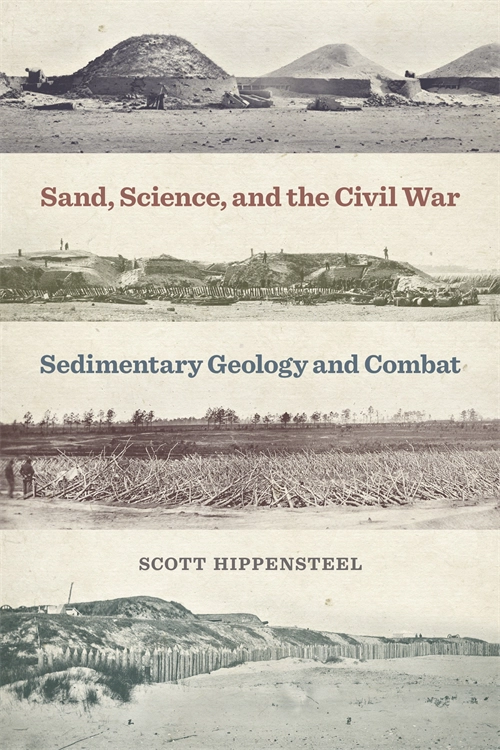

Scott Hippensteel is Associate Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. This interview is based on his new book, Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press, 2023).

JF: What led you to write Sand, Science, and the Civil War?

SH: I grew up near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and spent many days as a teenager hiking around the battlefield and studying the fascinating terrain. When I went to graduate school I choose natural history (geology, paleontology) over military history for my teaching career. During my twenty years at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte I’ve written many journal articles about how microfossils can be used to solve environmental and archaeological problems, and this led me to join the research team associated with the Civil War submarine H.L. Hunley. This allowed me to use science, and specifically sedimentary geology and micropaleontology, to help solve an important mystery from the Civil War – why the crew members’ bodies were so incredibly well preserved after resting on the ocean floor for more than 150 years.

While I was working on the sediments and fossils from the submarine, I took my family to visit the Stones River National Battlefield. We happened to be visiting on the 155th anniversary of the battle and it was the first occasion ever that the National Park Service allowed reenactors on the actual battleground. While I watched men pretending to fight and taking cover in the natural limestone trenches at the center of the Union line, it occurred to me just how much geology benefited the federal defenders. Sedimentary geology was a force multiplier, and this was true for nearly every other battlefield I considered, and especially for those along the coastlines and rivers.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Sand, Science, and the Civil War?

SH: Historians have vastly underrated the influence of sedimentary geology on the fighting of the Civil War. Sediment influenced the strategy, tactics, and combat of the war on multiple scales, from the formidable Confederate sand fortifications guarding southern ports to the cobbles thrown when ammunition ran out, sedimentary geology played an important role.

JF: Why do we need to read Sand, Science, and the Civil War?

SH: I’ll quote one of my reviewers to start my answer to this question: Kenneth Noe, author of the excellent book The Howling Storm: Weather, Climate, and the American Civil War, summed up my book as such: “Sand, Science, and the Civil War is a wholly original work. . . . As a Civil War historian I was often fascinated with his insights and conclusions. It’s the best thing I’ve read on coastal fortifications, and fascinating points crop up throughout.”

A second reason to read the book relates to historical interpretation of military events. For example, many of your readers will be familiar with the award winning 1989 film Glory, starring Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick. Near the conclusion of the movie, their unit, the 54th Massachusetts, attacks a sand fortification outside of Charleston named Battery Wagner. The fight, which has been very well documented in our history books, was a bloodbath. What isn’t as well known is how much sedimentary geology, and specifically sand, had to do with this disaster. For example, the Union officer in charge of the operation, Quincy Gillmore, ordered that more than 10,000 heavy artillery round be fired into the Confederate fortification before the assault. He assumed this would disable the defensive artillery and destroy the enemy garrison. Instead, the sand absorbed the impact of the heavy shells and the left the defensive capability of the battery nearly completely intact. The ten-hour bombardment, at times raining shells at two-second intervals, had killed only eight men and wounded only twenty. Gillmore’s grand assault on Battery Wagner turned disastrous for the Union, who suffered more than 1,500 casualties during the failed assault (more than 30 percent of the attacking force). The outnumbered Confederate defenders, sheltered in the sand, lost only 222 men.

A third reason to read the book is simple – we tend to underestimate the role of sedimentary geology on military events. One needs to look no further than the Russian tanks sinking in the mud in Ukraine to see examples of military leaders failing to learn the lessons from the past about the influence of sedimentary geology on warfare.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

SH: I’m not really, my PhD is in geology. I am a scientist and I teach classes on coastal geology, paleontology, environmental geology, and sedimentology. Nevertheless, I am fascinated by the interaction between science and history and I write books about how science can be used to interpret the past. For example, my last book, Myths of the Civil War: The Fact, Fiction, and Science behind the Civil War’s Most-Told Stories, used physics, mathematics, meteorology, and geology to debunk many of the most repeated stories from the Civil War. For example, there was no such thing as a Civil War “sniper”, bullets never “fell like hail”, and the rifle musket was a vastly overrated weapon.

JF: What is your next project?

SH: I have a few projects in the works. I’m about half finished writing a book about how science can be used to interpret the fascinating black and white photographs from the Civil War. This manuscript deals with the role of Civil War photographers as the first photojournalists and asks some tough questions – Can Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner, for example, really be considered photojournalists if more than one-third of their “combat” photographs were clearly manipulated in some manner?

Another book project I’m putting together involves American military history and geology. From Bunker Hill, to the invasion of Normandy, to the Gulf War, geology — and especially sedimentary geology — has played an important, if greatly underrated, role.Another book project I’m putting together involves American military history and geology. From Bunker Hill, to the invasion of Normandy, to the Gulf War, geology — and especially sedimentary geology — has played an important, if greatly underrated, role.

JF: Thanks, Scott!