Work, marriage, and worship require more than a shrug

When I first moved to a new city a little over six months ago, I knew that in order to make friends and embed myself in a new community I had to be a “joiner.” I had to say yes to every offer of social engagement that came my way, and I had to be an active participant rather than a passive observer. For an introvert like me, this proved difficult. But it was exactly the right strategy. Although I ended up at a few parties I immediately wanted to leave (I think my shortest stint was fifteen minutes), on the whole, I developed a close circle of friends and a wider net of acquaintances. Above all, I felt like a member of a new community.

But recently I have been battling a pernicious ailment, common among young adults, that is slowly pulling me from the threads of my community: maybe-ism.

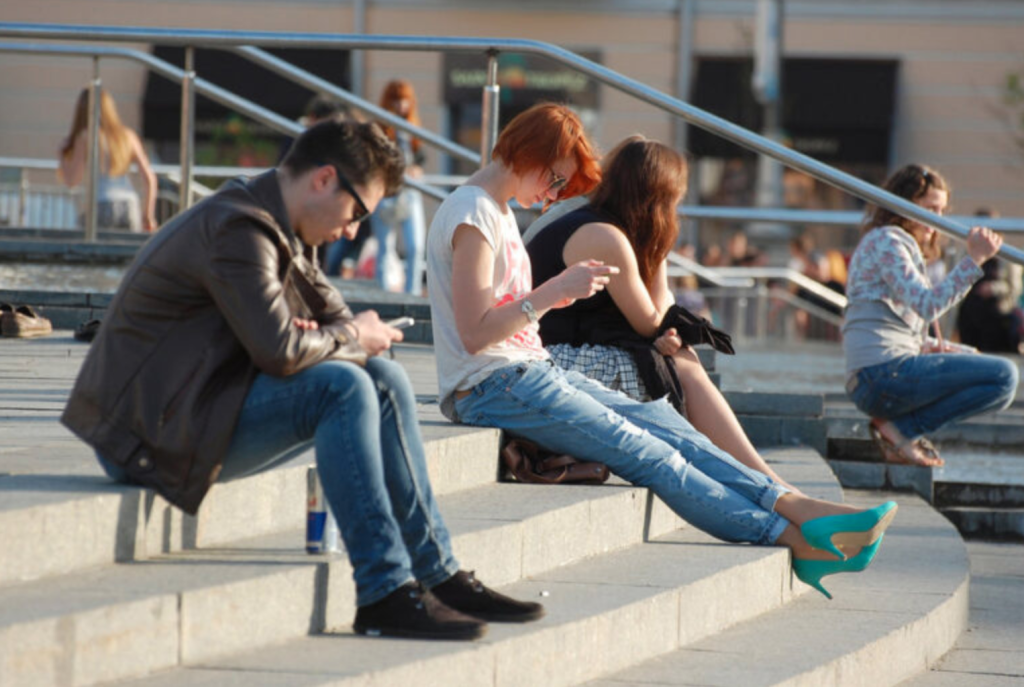

Maybe-ism is the tendency to avoid committing to social engagements—not due to competing obligations but simply because we are not sure we want to endure the effort of being a joiner that day. People typically deliver these maybes under the guise of uncertainty or some alternative responsibility, and the decision to engage in the affair in question is deferred to some future time. While maybe-ism isn’t nearly as pernicious as flake-ism (the tendency to commit to such engagements but drop out at the last moment), our collective tendency towards “maybe” prevents us from deeply embedding ourselves in friendship and community.

Maybe-ism is not all bad. Flexibility is undeniably valuable, and everyone recognizes that we cannot possibly say yes to everything. Moreover, the inner economist in all of us is prudent to push off our decision to join or withdraw until we have more information. Who knows what other social opportunities might arise? Who knows whether I will have a stockpile of social energy that day? By waiting until the last socially acceptable moment to commit, we are able to make more informed decisions about our participation in social life, maximizing our social utility.

No one should be willing to fully sacrifice their ability to say maybe—many of the considerations above are important, and free choice is sacred. But here’s the problem: While maybe-ism has some clear utility when it comes to informal social engagements, it doesn’t stop at informal socializing. Maybe-ism appears to be a driving force behind many young people’s deteriorating engagement with core social and cultural institutions—the institutions that provide us with meaning. When it comes to our decisions to work, marry, and worship, “maybe” is not a viable response.

In the sphere of work, maybe-ism is pervasive, especially among young people. For one, a smaller share of young people is working today than twenty years ago. The share of sixteen to twenty-four-year-olds that are part of the labor force has declined from sixty-five percent in 2001 to fifty-five percent today. And the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that only slightly more than half (fifty-one percent) of young adults will be in the labor force in 2031.

For those who remain part of the workforce, flexible work arrangements have become the norm. Technological advancements—such as the rise of ride sharing and food delivery apps, as well as work-from-home technology—have fundamentally changed the way we work with each other. It should come as no surprise that hybrid work environments, characterized by workers’ ability to freely choose when to come into the office and when to stay home—have become the most sought after work arrangements.

When it comes to marriage, young people display a particularly strong tendency towards maybe-ism as well. Over the past half century, men’s average age at first marriage has climbed from the early twenties to over thirty. And adults are increasingly cohabiting before marriage, the overwhelming majority of whom say that it is a sort of “test-run” for marriage.

Maybe-ism is also apparent in the worship tendencies of young Americans. Although religion has been in decline across the board for several decades, young people seem to be driving this trend. Not only are fewer young people religiously observant, they are also less likely to be regular churchgoers. Even among those who claim to be religious, only twenty-eight percent of twenty-somethings attend church weekly, compared to thirty-six percent of the rest of the Americans, according to the General Social Survey.

To be sure, maybe-ism is not all bad in these cases either. Some may argue that these examples are evidence of young people taking advantage of their freedom and autonomy—something that should be celebrated, not a cause for concern. But when you examine each domain, it becomes clear that flexibility is not always the source of happiness and meaning—it may actually work in opposition to it. For example, more and more workers are dissatisfied with their jobs, and fewer Americans feel deeply engaged with their work. Divorce and marital instability have become the norm, and those who cohabitate before marrying are less likely to be happily married. Last, some suspect that the rapid rise in depression and anxiety among young people is at least partly attributable to their withdrawal from religious institutions.

The institutions of work, marriage, and worship are the very sources of meaning in our lives, and they require an active commitment, a joiner mentality, not a propensity toward maybe. However tempting the tendency towards maybe-ism may be—and however harmless it may seem—you can’t maybe your way into meaning.

Thomas O’Rourke is a policy researcher and writer who studies anti-poverty policy, economic opportunity, and social mobility.