The life of Crassus is worth remembering—especially on the ides of March

Crassus: The First Tycoon by Peter Stothard. Yale University Press, 2022. 184 pp., $26.00

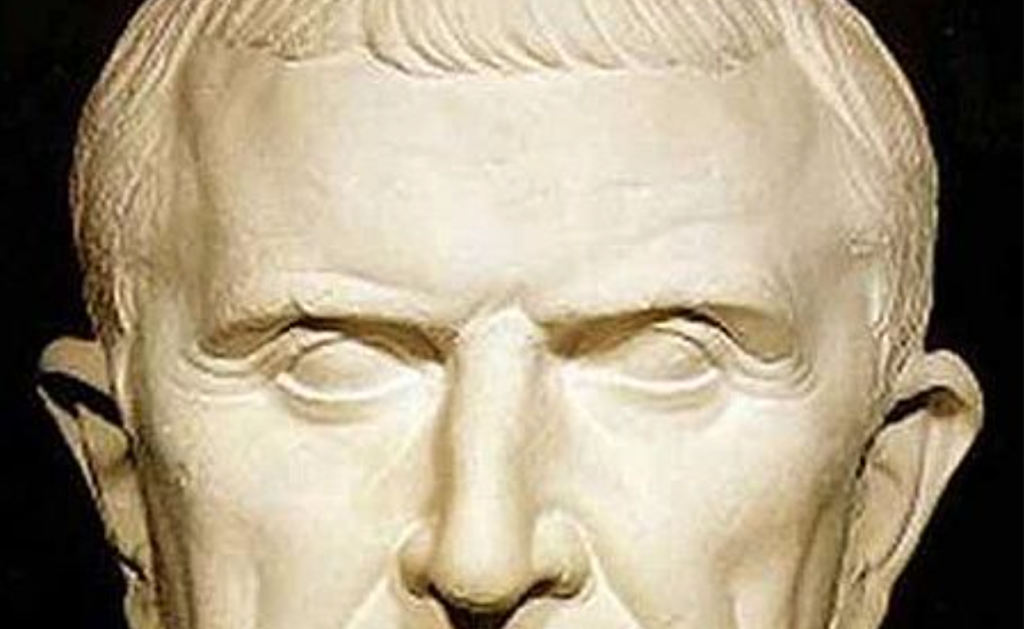

“The first tycoon of ancient Rome was also its most famous loser.” So begins Crassus: The First Tycoon, Peter Stothard’s new biography of Marcus Licinius Crassus, the Roman who defeated Spartacus, bankrolled a young Julius Caesar’s career, and lost seven legions and his life in Syria in 53 BC, four years before Caesar crossed the Rubicon. His disastrous defeat in Syria made him a failure, but according to Stothard he was “no ordinary failure, just as he had been no ordinary success—a man whose life as businessman and politician posed both immediate and lasting questions about the intertwining of money, ambition, and power.”

Stothard’s book is part of Yale University Press’s Ancient Lives series. Alongside Crassus in the series so far are lives of Cleopatra VII, Ramses II, and Demetrius I Poliorcetes (“The Besieger”). Crassus is the non-royal in the group; there was no throne that he aimed to obtain or keep. His ambitions remain obscured, and while his ancient biographer Plutarch paints avarice as Crassus’ main driver, his career and actions suggest more varied motives.

Apart from retellings of Spartacus’s revolt and occasional lists of history’s richest persons, where Crassus shares top billing with Mansa Musa, John D. Rockefeller, Carlos Slim, and Jeff Bezos, he holds no place in the popular imagination. He does not have the popularity and enduring cultural fascination of Cleopatra. Unlike Ramses, who remade Egypt with his many likenesses, there are no monuments to Crassus.

What Stothard’s Crassus offers instead is a man for the age of tech tycoons. Crassus here is an innovator and disrupter, who saw opportunities that others missed and found new ways to use money for political control. He survived the chaos and violence of the civil wars between Marius and Sulla. In the new world that followed the civil wars, Crassus made investments in land (especially of those killed in the wars), in slaves, and in other politicians. He adapted military methods to civilian enterprises and created personal fire brigades and construction crews. He made himself “the first tycoon” of a rebuilding city.

He forged a surprise alliance with a rival, Pompey, and a former protégé, Caesar, that shook Roman politics in the early 50s BC. Crassus, Pompey, and Caesar were “the three-headed monster” of Rome. They used that power to gain further military commands—a source of prestige and power that was older, more durable, and riskier than Crassus’s financial innovations. As Caesar’s power and fame grew through year after year of conquest in Gaul, Crassus’s ambition to be more than just Rome’s tycoon led him to plan his own campaign—a war against the Parthian kingdom, approximately situated in modern day Iraq and Iran. The war, carefully planned, led to disaster, as Crassus and his officers proved ignorant and unprepared for Parthian military tactics.

Crassus thus offers a cautionary tale of the innovator whose ambition and venturing outside the realm of his expertise lead to ruin. Modern parallels abound. Yet a danger in biography is that in looking at another we may see only ourselves. In the case of Crassus, the temptation may be to see a Zuckerberg, Buffett, or Musk—a modern figure in ancient costume.

Thanks to his interpretive moderation and emphasis on context, Stothard avoids this hazard. He is careful not to overstate Crassus’s financial innovations. Stothard stresses that Crassus was not a banker as we understand the term: his loans were short-term and his agreements often unwritten. Crassus’s ignorance of Parthian tactics on the battlefield is set against discussion of Rome’s relative lack of familiarity with all things Parthian. “There was,” as Stothard says, “never a Parthian population at Rome, none of the guides to understanding, or even prejudiced misunderstanding, that the Romans had for Greeks, Africans, and Gauls.”

The intense violence that sporadically convulsed the period known as the Late Roman Republic (133-27 BC) sets Crassus’s story apart from those of modern tycoons. As a young man during the civil wars between rival senators Marius and Sulla, Crassus saw his father’s head fastened to the Rostra, the speakers’ platform in the Roman Forum. The same spate of violence had claimed the life of an older brother. Crassus fled with a small group of friends and slaves from Rome to Spain, where he had family connections. For months he lived secretly in a cave there and bided his time until the more competent of his enemies at Rome died.

In this civil war Crassus was lucky. Less lucky was one Marcus Gratidianus, torn apart piece by piece in a torturous murder at the tomb of a man Gratidianus had driven to suicide in an earlier spate of political violence. Less lucky were the six thousand prisoners Sulla had executed, their screams in the background drowning out business during a meeting of the Senate at the Temple of Bellona. Then too there were the tens of thousands of Italians—men, women, and children—killed by supporters of the Pontic king Mithradates VI around the Aegean in the event that triggered the Marius-Sulla civil war to begin with. The violence of the Late Republic was sporadic but intense, the threat of violence always latent.

Unlike most modern tycoons, Crassus and other politically ambitious aristocrats could expect military service. In the Roman Republic there was no clean division between military and civilian authorities. Magistrates who oversaw court cases or regulated weights in the marketplace also served as junior officers and generals against Rome’s enemies.

Crassus was better known for his business acumen, but he also had significant experience on the battlefield. At the battle of the Colline Gate in 82 BC, which decided at last the victor in the Marius-Sulla civil war, Crassus led the right wing of the Sullan line of battle. While the rest of Sulla’s line fell back under pressure, Crassus’s men held firm and won the battle.

Crassus too could claim credit for the defeat of Spartacus’s slave uprising. More infamous than this victory was its aftermath. Crassus devised an efficient and terrifying punishment for the prisoners from the campaign against Spartacus. Crassus’s soldiers marched the 6000 prisoners along the Appian Way from Capua to Rome. Every thirty yards the march paused, and the last man in line was crucified.

For Crassus and his fellow citizens, the violence of the Late Republic was both expected—the Roman state was rarely not at war—and unexpected. After all, the scale of the violence of Marius-Sulla civil war had no precedent in Roman memory. The civil war created new opportunities for Crassus. The deaths of his father and older brother made him the head of the family, while the property of other murdered owners made for profitable if risky investments. Political murders opened up political competition for the survivors, and Crassus made investments in a wide net of political aspirants—”the next generation of dice throwers who might destroy everything.” It is in Crassus’s wide net that we find the figures who turned to political violence and played their part in ending the Roman Republic: Caesar, Catiline, Clodius, and Cassius, Caesar’s future assassin. Throughout Crassus’s life, disruption carried with it the seeds of future destruction.

For all the violence, money, and intrigue that surrounded him, Crassus was generous to the common people and unostentatious in his daily life. According to his biographer Plutarch, he lived simply. While other senators had multiple villas throughout Italy, for Crassus one house was enough. He opened both his house and his loans to all. He entertained non-elites at his home, and meals there were modest and cheerful affairs. When Cicero, Caesar, or Pompey were unwilling to act as an advocate for someone in court, Crassus would step in and meticulously prepare the case. Plutarch also tells us that he always returned a greeting in public, no matter how poor or insignificant the person.

This Crassus, as likely to greet a potter in the street as have a tenth of his own forces clubbed to death by their comrades as punishment for cowardice, was a puzzle to Plutarch and later writers. The way Crassus operated, behind the scenes in dealings that left few traces, certainly did no service to later historians. This scarcity of sources thus poses special challenges to potential biographers. Fortunately, in this brisk, lively, and accessible volume, Stothard presents a compelling portrait of Crassus in all his seeming contradictions.

Here Crassus is a man of the old world—a world where honor, military glory, and family pride were paramount. At the same time, he is creating a new one—a world where a tycoon could exert power through money and human capital. Crassus: The First Tycoon likewise serves both as a look into a violent, honor-bound, and largely alien past and as a strikingly relevant examination of how money, innovation, and power operate in times of rapid change.

Carolynn Roncaglia is Associate Professor of Classics at Santa Clara University. She is the author of Northern Italy in the Roman World: From the Bronze Age to Late Antiquity (Johns Hopkins, 2018).