As the Roman Republic was facing its death throes and he himself was only months away from ignominious death, the legendary Roman politician and orator Cicero wrote what would become one of his most influential essays since antiquity: On Friendship. It seems apt that feeling abandoned by those he had considered his life-long friends, Cicero indeed questioned whether he had any friends left at all.

It appears, at the end, that perhaps he did not. His execution in the proscriptions that followed the assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March 44 BCE was an act of revenge, directly ordered by Marc Antony, who took personally (imagine that!) the extraordinarily acerbic fourteen Philippics that Cicero composed against him. There is a lesson here, by the way: chances are, if you write fourteen brilliant orations denouncing someone, they will really not want to be your friend after that, not appreciating the brilliance of said orations. In fact, they might be really happy to sign an order for your execution, should they have the power to do so.

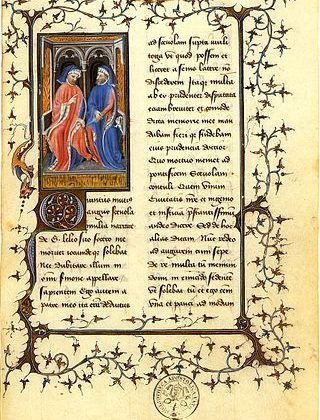

Like so many of Cicero’s writings, his essay “On Friendship” received much more love than its author both in antiquity and beyond. Followed up by such later figures as the French sixteenth-century essayist Michel de Montaigne, who wrote his own version of an essay on this topic, the various treatises on friendship have focused on a very particular type of friendship – that of intellectual men with other intellectual men.

Such friendships invariably involved a fellowship of ideas. And because a deep understanding of another person’s ideas is difficult to achieve, Montaigne in particular insisted that true friendship was exceedingly rare. Montaigne’s argument that he himself had only one true friend in his life—a notion that echoes the unique bond of marriage—brings to the fore an implied aspect of true friendship that often goes unrecognized. Like marriage, true friendship is based on vows. But unlike marriage, these vows remain unspoken, even if assumed by close friends who have known each other for years.

In such deep friendships, these vows presume the question that Jesus asked Peter three times in John 21: do you love me? Even if we do not need to ask our friends this question, we know deep within that the answer is a resounding yes, and that yes has implications about which Jesus reminds to Peter in that same conversation. Our loving unspoken vows to our closest friends assume a friendship that is embodied and service-minded, rather than entirely intellectual.

In other words, friends do not only want to understand each other’s ideas—although this is an essential starting point—but display care for each other in word and deed. The concrete shape of that care will vary, but you always know a true friend. As the Roman poet Ennius quipped in the often-quoted-out-of-context line—indeed, Cicero himself quoted it in his essay on friendship—”amicus certus in re incerta cernitur” (a true friend is proven in challenging times).

Indeed, it is right for me to reflect on true friendship right now for two reasons. First, it was exactly three years ago this week that the entire nation went into lockdown to slow down the spread of COVID-19. That lockdown disrupted friendships, but also forced people to figure out different ways to show care for friends, near and far. And second, around this time a little over four years ago (it was in January), I was expecting my third child. We live far from family, and I was worried about potentially going into labor at a time when no one else might be available to come watch my two older children.

A kind friend from church, unasked, offered to help. For the full two weeks that I went past my due date, she drove everywhere with a packed overnight bag in her car, just so she could be ready to drop everything and come to my house the minute I called her. On the night when I finally went into labor and called my friend, it was just after midnight. Carol, whose house is located fifteen minutes away from mine, arrived in ten minutes, breaking land-speed records to come and help. Ennius was right.

To me, this is a concrete example of distinctly Christian friendship. It reflects care—a care manifest in prayer, as I know that this friend and many others were praying for me and for my baby. But also, this is a friendship that displays practical embodied forethought of the kind that, perhaps, Cicero or Montaigne, immersed fully in their thoughts as they so often were, would not have understood. And this practical element, I would argue, is also distinctively Christian, even if it has been inherited and absorbed by the secular ideals of friendship in our own world. Who wouldn’t want a friend like Carol, after all?

Reading pastoral works of early Christian bishops, it is clear that networks of friendship and care overlapped regularly. Christian friendship recognized not just a fellowship of disembodied minds, but the need to care for each other in a world that did not have any such networks of genuine care—the Roman Empire. Networks of care, after all, assume a valuing of every human being as precious and valuable. This view did not exist in the pagan world, where the worth of every person was determined by his or her social, economic, and health status.

I think about this in our own world, as networks of friendship and care have been strained by the crisis of the pandemic. There was the dreadful fear at first, as the world was figuring out the nature of the disease, that by showing care for someone, we might inadvertently infect and kill. And then there was the disruption of in-person interactions that affected habits. The temptation to withdraw from the world is real, especially for introverts. Once re-conditioned to live within a bubble, it is harder to re-emerge from it.

But we are far from the first people in world history to deal with these temptations. The early church pushed people in the Roman world to get out of their comfort zone and befriend those whose worth they would never have acknowledged otherwise. Friendship, as Jesus’ question to Peter reminds, requires loving others in a way that is no less uncomfortable today than it was two-thousand years ago.