Books open up our lives—to ourselves, and to one another

Do you know what I miss? The stamped cards at the back of library books. As a kid who frequented libraries, I was fascinated by these records of previous readers. Reading is such a solitary activity and, like writing, it has always struck me as similar to scuba diving: We submerge ourselves in a world of words. The checkout cards showed you that there were others who had gone before.

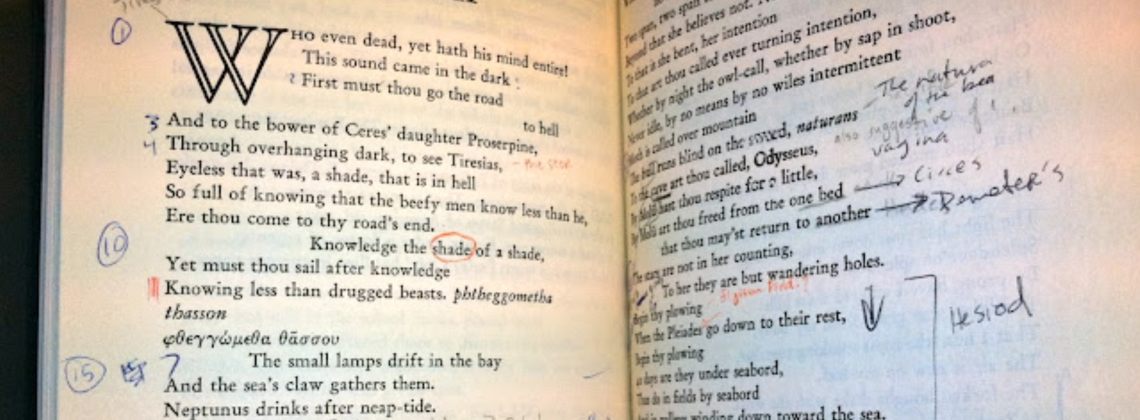

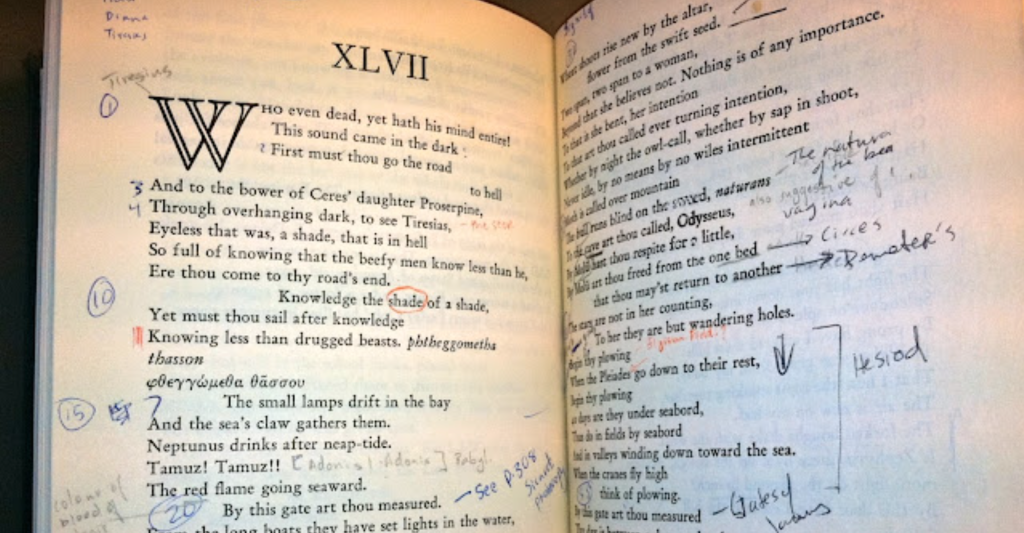

Maybe that’s why I love marginalia. Like Rebecca McClanahan says in “Book Marks,” “Studying the clues readers leave in books is one of my obsessions—tracking the evidence and guessing the lives beneath.” Marginalia reveal someone’s private reckoning with ideas, a reverie from a particular place and time.

Since college I have had an edition of Shakespeare’s plays, and the previous owner marked her name across the book’s side: “Lisa.” For over twenty years I have read poetry and plays alongside Lisa, noting her delight in the comedies, her indignity at the Christians’ treatment of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, her attention to Helena’s misery in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. With my own notes in the margins, this book is now crowded with chatty banter about the plays we both like.

At the college where I work I’m always on the lookout for marginalia, noting the students’ conversations with their books. In our library’s copy of C. V. Wedgwood’s A Coffin for King Charles, for instance, a previous reader wonders about the state of Shakespeare’s soul, not to mention modernity’s “anti-theistic hysteria.” A colleague who recently retired gave me a stack of old paperbacks, and I have his gnomic expressions—“poignant,” “we live our lives unconsciously,” and “we grieve over what is gone”—in the margins of Our Town, The Crucible, and Paradise Lost.

And of course I keep the marginalia from loved ones. I treasure these marks the most. Recognizing the angle of the cursive, the hurried hand, the careful script, I know the words by heart. With marginalia, you can recover their authors’ interests and expressions, and that’s why I save them: because I can hear their voices.

When I was sixteen my grandfather gave me a book, and while it doesn’t have marginalia, he did write an inscription to me, endorsing the contents. He was a shy man and certainly inscrutable. My grandmother said he was the smartest person she ever knew—the most interesting too. When I hold this book and read my grandfather’s handwriting, I can hear his voice. “Thought you might want to read this,” he says. Even his words on the page are terse.

Years after he gave me the book, he called me on the phone, and we talked about home and school and the weather. Days later he took his life. This last conversation was so different from how we usually spoke to one another: He asked questions, laughed, and ended the conversation by telling me he loved me. I was dumbstruck.

You’d think that maybe, just maybe, I might have recognized what was really happening, that I could have better imagined my way into his situation, could have seen the gesture for what it was, a valediction.

People are mysteries to me—loved ones especially. In many ways, my study of literature is about trying to understand people—making sense of who they are, what they think and feel, what counts for reliable evidence, and how to love them. The stakes of getting it right bring to mind my grandfather, someone I’ve thought about for almost twenty years now.

And what about the book he gave me? It is the story of a grandfather who goes on adventures with his grandson and teaches him about the world. It’s difficult not to see this story as my grandfather’s wish for the two of us—something he never accomplished, was incapable of doing, debilitated as he was with shyness and depression, but that he wanted nonetheless. God help me, I don’t even remember reading the book when he gave it to me. It’s a lesson in how the page can hold our deepest desires. And what if I had read that note better, that last conversation too, and had loved him better, crossing the distance from my world to his?

Prompted by questions like these, you might think my grandfather’s tragic end eclipsed everything else about him, and for a while it did. But what has emerged over time is love. The thing I keep, that I carry with me, is the recognition of his efforts to reach out in the midst of tremendous pain. He gave me a book he wished were true. He called to say goodbye as best he could, to say he loved me. These gestures are as legible as his inscription, and I’ll be reading and re-reading them for the rest of my life.

Robert Erle Barham is Associate Professor of English at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, GA. He is the deputy editor of Current.