College is an interesting time. You get constant social approval for Chili’s and Taco Bell. Staying up all night to read Beowulf isn’t all that weird. You worry about “printer money” and parking and what you’re doing for spring break. You can cycle through majors and every semester is different. Many people form intense attachments to their friends, a few faculty members, and a lifestyle that some will later consider their peak.

For many reasons, people look back very fondly on their time in college. Though it sometimes seems stressful, you later realize how relaxed it actually was. It is also a time of incredible self-discovery for students. Many begin to distinguish their own ideas and ambitions from those of their parents. Some people discover passions and vocations that they will pursue for the rest of their life. Many people form friendships that will see them through some of the most formative years of early adulthood.

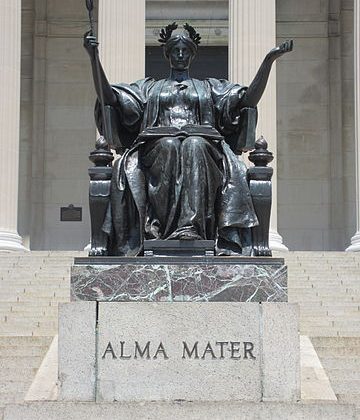

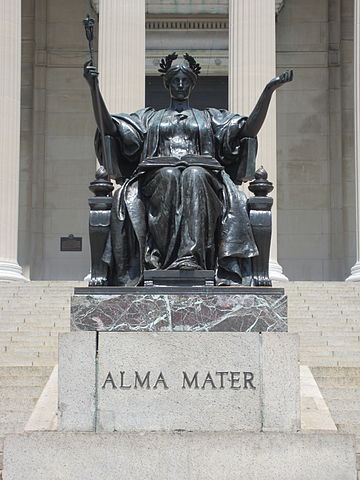

There are so many reasons for you to love your alma mater. It comes as a bit of a surprise to find out it will almost certainly let you down at some point. It is not even unusual for you to hate it sometimes.

For so many students, college is the pinnacle of idealism. After all, life is still mostly ahead of you. Everything is new and many things are exciting. Around you are adults who have devoted their lives to ideas and discovery and education. You are encouraged to form and hold idealistic thoughts. Many people are more purist than pragmatic when it comes to their politics, or their vision for their own career path. You have the energy of youth and the relative inexperience of it, too.

The good parts are actually what make it impossible for your school to stay on your good side at all times. The very institution that exposed you to certain ideals will fail to uphold them at some point. You will see more pragmatism than purity in university politics. You will wonder what the administration is up to anyway. Someone will take forever to get your transcript to you. Someone will forget to write your recommendation. Your dorm room will be a disappointment. It will seem like the institution isn’t running the way it should.

Once the questions begin, they can’t be stopped. How can the very place that emphasizes the life of the mind insist on all of these supplementary fees? How can they not have parking for everyone? Why aren’t there more food options for people with food allergies in the cafeteria? Who is running athletics, anyway? You may even think that these are the particular flaws of your particular university, not realizing they are essentially universal.

Alumni can be even more easily outraged. Once they graduate, some students can quickly turn to hating their alma mater. It is very easy for them to become “ashamed” of it and to “regret” their time there. We can be “disappointed” in how quickly students and alumni get “disappointed” by their alma mater, or we can try to understand what is going on.

In one way, it’s just a matter of timing. A university is one of the first immovable objects you come across as an adult. It is an institution you belong to by choice and it is consistently imperfect and seemingly unwilling to adjust to your expectations. For many people, it is also their first adult experience of forms and bureaucracy and an unfiltered taste of the patience-demanding life that will never end. You are in the “system” now and not at all in control—even though you can stay up as late as you’d like and make so many other consequential decisions. No wonder there are so many undergraduate libertarians.

College coincides with some of the highest expectations of your life and for your life. Conflict is inevitable. At no other point in your life are you likely to get so worked up about Styrofoam in the cafeteria, parking policies, two points on a midterm, the opinions of someone one year ahead of you in life, and the condition of the sidewalks. You are not altogether likely to argue metaphysics with others later in life, either.

Wrestling with your university is almost a stage of life in figuring out relationships with institutions. As we age, there are many institutions which we enter by choice. All are imperfect and hard to adjust. How can we make them better? How do we know when to leave? What is worth holding on to? Students and recent alumni are learning this in real time.

The words and experiences of a university do not always align. They can’t. College is about empowerment. But students are not nearly as powerful within the system as they would like to be. You are an adult, but the other adults around you have a considerable amount of control over your future. People can say and do things to you and you cannot respond as a child, but neither can you respond as a peer. Most students have just come of voting age, but decisions aren’t made all that democratically when you consider that students aren’t fully enfranchised in university politics.

The more you love the place and the more your life is invested in campus, the less inconsequential anything there can be. The gap between ideals and reality is even worse if the college is private, because the whole experience is built on ideals and shared community. Any disappointment seems like a betrayal. And, of course, most students are paying for this experience.

All institutions need criticism and correction, but very often students who see the problems are unable to effectively communicate about them. Students are typically unaware of existing channels for change. Other times they won’t be around long enough to see progress with the glacial pace of university change. And other times the university truly intends to just wait them out.

What can students do with their frustrations? What can they do when they identify genuine problems? When they are unable to use existing channels for change, or are unaware of them, student idealism can lead to unrealistic expectations and sometimes extreme rhetoric in seeking administrative responses. This often causes them to be ignored, which does not make them more effective but does make them more disillusioned.

What is to be done? Universities are good at teaching ideas and idealism. We’re good at getting people ready to go change the world. We’re not good at teaching people how to hold ideals in the real world, which will not meet their standards or change on their timeline. It’s not that we need compromisers or people without ideals. Far from it. But we do need people who can commit to change even when the process is imperfect or demands incredible patience. And we need to teach people how to discern what will be effective in changing any given institution.

Resolving your relationship with your alma mater is part of making sense of your origins. All of us are the product of complicated circumstances and environments, which do not always reflect the way we wish the world to be. Sometimes students think you can have the people and the experiences, but not the institution. The confusing truth is, the people you loved and the place that frustrates you—they fit together in some way. All of those formative professors, they were paid to inspire you. It is easy to forget that the very experiences we enjoyed came from that “problematic” place. At some point, we have to consider that even flawed institutions can provide for some human flourishing. The good times and relationships don’t excuse the flaws, but they can tell us if a place is worth fighting for and if there is something to build from.

The frustrations of students as they realize the inadequacies of their chosen institutions should be recognized and respected. But while the passion and idealism of youth are a beautiful part of the college experience, they are not enough on their own to make the world a better place. We need that energy, but we also need to learn how to channel anger into effective change. If we burn everything down, there won’t be many buildings to take shelter in when it starts raining. Can we learn to work toward the good even when we know we will not achieve the perfect? The university is certainly as good a place as any to start to figure that out.

We can think of the university as a farm. It needs to be cared for and cultivated. It genuinely needs weeding and attentive watching. When things go wrong, it can be devastating. If they go wrong enough, people go hungry. Denial does no good. How will we respond to the bad seasons? Students and alumni are sometimes better at salting the fields than tending them. You can turn your back on your university, but that won’t turn it into a better place. If it is a farm that can still produce good crops, then we have to help it back from things like drought and hail. We can hate the hail, but we also have to mend the fences and nurture the good seeds and keep the rabbits out of the garden. That takes persistence and hard work, patience and care.

Elizabeth Stice is Associate Professor of History at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Her essays have appeared at Front Porch Republic, History News Network, and Mere Orthodoxy. She is a regular contributor to Current and blogs weekly here at The Arena, where you can catch her posts every Monday.