In the face of our social silence, human kindness is an irreplaceable balm

In 1998, at the age of fourteen, I got into a minor upset at the mall with some of my friends. I don’t remember the specifics—something like someone making a lewd joke, or someone putting someone else down, or somebody talking about shoplifting but not actually doing it. It was all fine in the end, but I do remember thinking, “I probably should not tell Mom about this.”

Three years later, in 2001, I sat in my dorm room during my very first week of classes at Middlebury College, 3000 miles away from my California hometown. I was not in any sort of upset at all; I was thrilled to be starting off on my brand-new Vermont life. Then the phone rang, and I remember thinking, “Oh, yay! Maybe it’s Mom!”

In 2009, I called my father from graduate school to tell him that my boyfriend and I had just become engaged. I was on cloud nine. I remember Dad saying, “Mom and I are so happy for you!”

In 2020, I lay on the living room couch, the care of three children and a newborn weighing heavily upon me as I struggled to survive a frightening bout of severe postpartum insomnia. Should I check into the hospital? “I wish my mom could come help me,” I thought.

But my mother had died twenty-three years earlier, in 1997.

In our pain-avoidant society, long-term grief is hidden, complex, and misunderstood. Our only remaining rituals of grief surround the funeral and its immediate aftermath: two weeks, maybe six at best. Then we all move on, leaving the bereaved to manage as best they can and hoping that their grief will be relieved by someone else. We are not heartless. We simply do not know what else to do. We fear causing pain by saying the wrong thing, just as we fear expressions of grief and the terror of a “scene,” so we tend to quietly let ourselves off the hook. We offer little acknowledgment that grief comes not all at once, but over many seasons.

Although my mother died more than twenty-five years ago, her loss has continued to surprise me with new episodes and seasons of grief. Grief often strikes me unexpectedly, arriving like a thief in the night. You might think that I would especially miss my mother on my wedding day, or on the anniversary of her death, or when I saw other teenagers having lunch with their moms. But that is not the case. It is when I reach down to get a pan out of the cupboard, when I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, when I hear a southern accent, or when the phone rings and I forget that she is dead.

Sometimes such an experience is a harbinger of a longer period of grief, of days or weeks of renewed processing to come. At times the grief is sweet and helps me remember the beautiful gift of a mother who loved me unconditionally. Oh, how well she loved me! But at other times the grief is so crushing as to take my breath away. My body shudders and my heart breaks and sometimes I even swoon a little, all because the motion of tying a child’s shoelace, or the smell of vanilla, or a particular sort of warm breeze has reminded me of the staggering vulnerability that is loss.

My current community, a highly religious, tight-knit town in rural Virginia, is an exemplar of excellent immediate support for the grieving. Funerals are packed, and fundraisers for the bereaved exceed their goals by thousands of dollars. Meal schedules overflow in the first weeks. Yet once the funeral is over, what remains? Only whatever support is given in secret. I am sure that some families receive meals and calls and cards and continued help for months and even years to come. And I am also sure that others do not.

Once I sent an email to some acquaintances to invite them to come pick from my flower garden. One woman shared with me that she planned to bring the bouquet she was picking to a relative’s grave, and then she apologized, afraid she had overstepped by speaking of loss. But it was only this small faux pas that made it possible for us to discover what we shared. If we had followed the rules, we would have remained disconnected, never knowing that a deep and understanding fellowship was only one broken boundary away.

Such stifling mores, intended to smooth over pain so that we can continue to function, form the foundation of how we handle long-term grief in our society. Our delayed experiences of grief are anything but public, anything but understood. Just as a young adult thinks he or she understands parenting before having children, we think we understand grieving before we experience a major loss. Since we have no rituals or customs for supporting long-term grief and since talking about death is taboo, we do not realize that the long-bereaved still need our help.

The truth is that long-term, seasonal, repeated grief from a single loss is common, especially when the loss occurs during childhood. While healthy grieving eventually results in a sort of peaceful remembrance, even the best grief will still bring renewed pain in seasons to come. And although speaking to a friend or neighbor about their grief or ours may elicit discomfort or rejection, it also may cause a strengthening of bonds and a renewal of honesty. There is no way around grief, but going through it is easier when the light is on, and often it takes a friend to flip the switch—it is too much for the bereaved to have to broach the matter him- or herself.

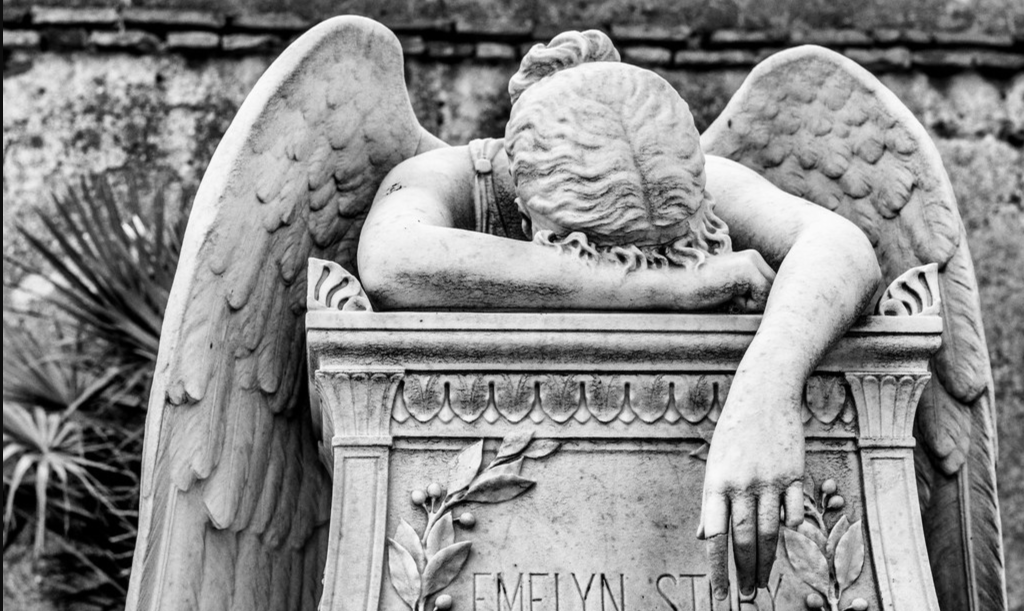

During my most recent season of grief, I took long walks as a form of relief. One afternoon, unable to visit my mother’s own grave, I walked a good three miles to a hilltop cemetery across town instead. There, lying in the winter sunshine near the Civil War veterans and the miscarried babies and the mothers and fathers of the past, I felt comforted and connected. The community of grief is real; it is just hidden, whether behind the great veil of death or just behind modern social silence.

That same day, I reached out to a friend who had lost her mother the year before. We don’t always know what to say to each other about our pain, my friend and I. But we can be together in it, and knowing each other’s grief makes all the difference.

So let us not fail to speak of grief any longer, our own or that of others. Are we really so rudderless as to let pain turn us away from each other? For simple human kindness is the great enemy of distress, and grief can only really harm us when we are alone.

Dixie Dillon Lane is an American historian, teacher, and essayist who writes frequently for Hearth & Field and Front Porch Republic as well as other publications, including her website, TheHollow.Substack.com. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Notre Dame.

I am grateful that you are willing to speak about these realities. I too have found that it is small moments that catch me out.

I’m glad the essay spoke to you, Timothy. I’m very sorry for your loss.