A new biography of Hilma af Klint forces a question: What is the purpose of art?

Hilma af Klint: A Biography by Julia Voss. University of Chicago Press, 2022. 440 pp., $45.00.

In practical life one will hardly find a person who, if he wants to go to Berlin, gets off the train in Regensburg. In spiritual life, getting off the train in Regensburg is a rather usual thing. Sometimes even the engineer does not want to go any further, and all of the passengers get off in Regensburg. How many, who sought God, finally remained standing before a carved figure! How many, who sought art, became caught on a form which an artist had used for his own purposes, be it Giotto, Raphael, Dürer, or Van Gogh!

Kandinsky “On the Question of Form” 1912

About halfway through her biography of the Swedish artist, Hilma af Klint, Julia Voss turns to Kandinsky’s words to draw a parallel between the aims of af Klint, a heretofore virtually unknown abstract artist, and her exact contemporary, the well-known Kandinsky—known in part for his claim to have painted the first modern, non-representational image. For Kandinsky, any attachment to naturalism in art is the equivalent of “disembarking at Regensburg,” a city actually quite far from the goal of “Berlin”: fully abstract—and therefore fully spiritual—art. This also, Voss argues, is true for af Klint.

Kandinsky’s ghost haunts the pages of Voss’s biography. He shows up in the chronology of af Klint’s life that opens the book. He’s named on page one and again in the very last pages, and on many pages in between. If there is one point Voss wants to make, it’s that the history of abstract art needs to be re-written. In this newer, truer version, Hilma af Klint and her circle should play a pivotal role.

Hilma af Klint (Hilma’s family was ennobled in the late 18th century; “af” is the Swedish equivalent of the German “von,” indicating aristocratic status) is indeed a remarkable person and a remarkable painter. Born in 1862 into an unusually liberal, naval family, she was among the second generation of women allowed to attend the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm. As a young artist, she won prizes for her work and exhibited history paintings, landscapes, and portraits.

Not unusually for the time, af Klint was also interested in spiritualism. After her first art teacher, Bertha Valerius, introduced her to like-minded people, she began attending seances around the age of seventeen. Valerius, herself a medium, received many messages during the mid-1880s from “Eon,” predicting a future in which a higher form of inspiration would result in completely different expressions of art. In 1886 af Klint received, via a different medium, a message from “Lorenz,” her “guardian spirit,” who told her she had a special mission. Unfortunately, “Lorenz” provided no further details.

In 1891 af Klint received her first direct communication from the spirit world. Using a “psychograph” (the forerunner of the ouija board) she was given instruction to “Go calmly on your way thorough life.” Later that year, the spirits told her she would “receive a great gift, if she never forgets the power of the highest.” Voss’s biography is the well-told, well-contextualized tale of af Klint’s calm perseverance in pursuit of her gift.

That same year, 1891, af Klint won a study grant from the Royal Academy, demonstrating that she continued to be part of Stockholm’s artistic community. Voss notes that “[d]ocuments from Hilma’s early years as a professional artist are extremely scarce and offer only fragmentary impressions.” By the end of the century af Klint, evidently short of artistic opportunities, was working as a seamstress. The turn of the century found her, along with her art school and spiritualist friend Anna Cassel, accepting a commission from John Vennerholm, the director of Stockholm’s veterinary school, for a series of anatomical drawings of horses for inclusion in his book on equine surgery. In 1901 and 1902 she provided illustrations for children’s books. A 1903 newspaper article mentions the sale of nine watercolors. As Voss notes, “none of this suggests resounding professional success.”

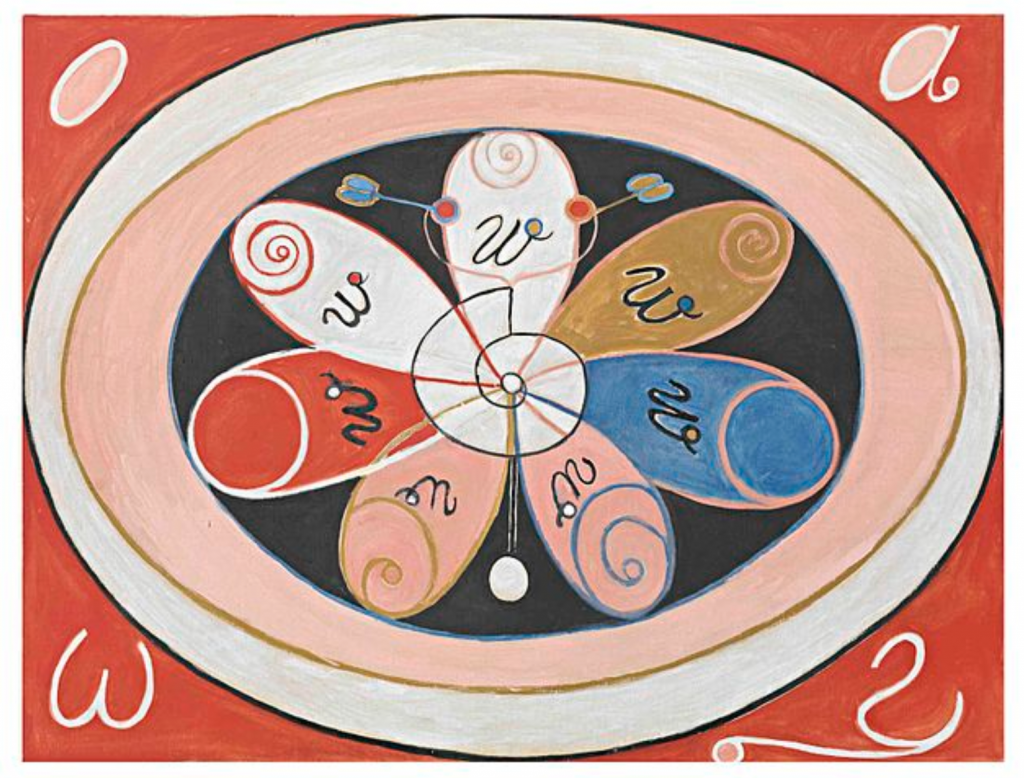

1904 was Hilma’s watershed year, the year in which her identity as an artist began to merge with her spiritualism. From this point onward af Klint’s vocation would be to realize “astral paintings.” These were images derived from spiritual communications from a variety of “higher ones” bearing names like Ananda, Gregor, Georg, and Amaliel. She did not do this in isolation. Receiving these spiritual messages and working out their visual implications was a communal endeavor that she pursued in small, shifting associations of like-minded women. Interestingly, a number of af Klint’s companions in this work were also trained artists. All of them were convinced of the importance of her work; none of them, including af Klint herself, had a clear understanding of its ultimate meaning.

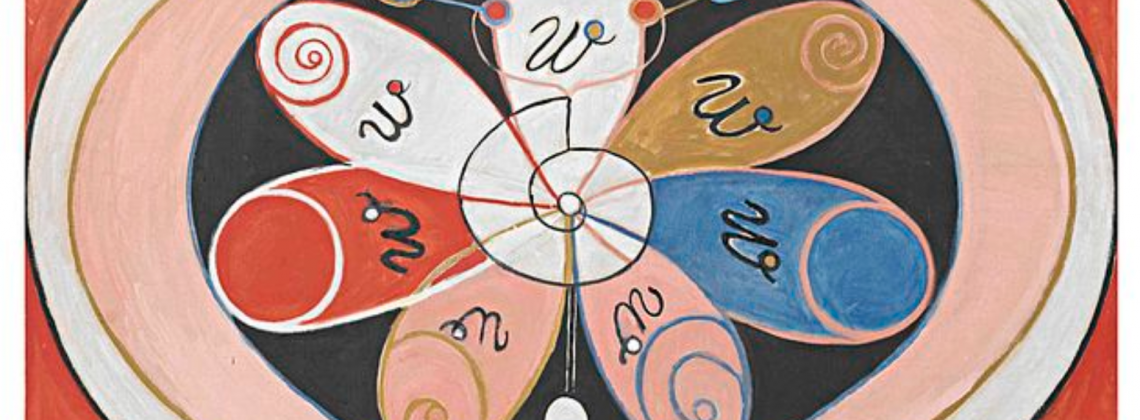

Over the next twenty years or so af Klint created well over a thousand paintings in upwards of eight series. Some panels measured seven by ten feet. She also filled thousands of pages of notebooks with the messages she received from the spirits and with her own attempts to decipher the meaning of these messages. The reproductions in Voss book cannot do justice to the power and presence of af Klint’s paintings. Curious readers will want to watch the 2019 documentary Beyond the Visible: Hilma af Klint, (which draws extensively on Voss’s study) for a clearer sense of the scale and scope of her imagery.

Throughout these years af Klint still accepted the occasional commission for a portrait. She exhibited the odd landscape here and there, but her life’s mission, to which she remained faithful to her dying day, was to offer her astral paintings to the world. And in this she failed. At least during her lifetime.

But not for lack of trying. Voss’s heroic work in af Klint’s large archive details the lengths the artist pursued attempting to exhibit or even gift her work to the circles she thought should be most receptive. She approached spiritualist, theosophical, and anthroposophical societies not just in Sweden but in Germany, the Netherlands, and England as well. She actively pursued contact with Rudolf Steiner and other leading lights of the spiritualist world. She found occasional willing collaborators in Holland, London, and Sweden. But none of these efforts bore long-lasting fruit.

In 1932, at the age of seventy, after nearly thirty years of faithful striving on behalf of the “higher ones,” af Klint came to a remarkable conclusion. “She didn’t doubt her work, but she doubted her contemporaries.” She decided to prohibit the exhibition or study of the vast majority of her work until twenty years after her death. With this, “she locked her work in a time capsule and hurled it into the future.” In fact, it would take over fifty years after her 1944 death for af Klint’s artistic output to receive any positive recognition. That finally came in 2018, with a massively popular show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Voss’s biography offers a salutary corrective to the history of art. But the fate of af Klint, her work, and her legacy illuminates more than just the inner workings of the discipline of art history. It exposes the formative power of two deeply ingrained and intertwined assumptions of our modern, western, post-enlightenment art world. Re-writing the history of abstraction with Hilma at its core cannot ignore these assumptions without seriously distorting af Klint’s own sense of the value of her work.

One assumption, inherited from Immanuel Kant’s notion of disinterestedness, is that “art” as such can have only one purpose, and that is to be regarded as “art,” displaying some sort of intrinsic excellence apart from any kind of interest, whether that interest be in its creator, its ability to convey a message, its monetary value, its ability to coordinate nicely with one’s sofa, or even its actual, physical existence. Granting af Klint entry into the hallowed halls of “art” on these terms would betray her own conviction that these pictures are more than “art.” They are revelations. Moreover, they are revelations in urgent need of a larger, spiritualist interpretive community.

The year before her death, af Klint decisively rejected a generous overture to display all her work in a dedicated facility and be given studio space, living quarters, and medical care. “Despite your interest in what I produced,” she responded to her would-be benefactor, “you still didn’t understand its higher origins.” That said, af Klint’s work would not be the first to be stripped of its higher origins upon entry to the temple of art. A stroll through most art museums will yield hundreds of objects, pre-modern and non-western, that have been similarly evacuated of all significance save their aesthetically expressive forms.

In his 2001 book, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, philosopher Larry Shiner elucidates the origins of our modern notion of “art” in the eighteenth century, its consolidation in the 1830s, and the ways in which this new understanding radically reorganized how the west valued, understood, and encountered “art.” Were Shiner to evaluate af Klint’s work, he would probably place her paintings alongside those generated by other “resisters” to the idea of purely aesthetic “art”—resisters like the early nineteenth-century German Nazarenes and the mid-nineteenth-century English Pre-Raphaelites. Both groups understood art to have a higher purpose than just being aesthetically pleasing. For them, art should give shape to moral values and direction to communal aspirations. Art should function in service to a particular, religiously organized community, as they imagined that it did during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance.

The question of community brings us to the second assumption that shapes our modern, western notion of “art.” George Dickie describes this in his “New Institutional Theory of Art.” He characterizes our art world as a social compact, a set of tacit, interlocking, learned agreements between makers and viewers, that certain kinds of artifacts, presented in certain settings under certain conditions, get to count as “Art.” “Art” is a social practice.

This claim clarifies to some extent why MoMA declined to include af Klint in its 2013 show “Inventing Abstraction.” The curator for that show, when questioned about the omission, noted that af Klint “painted in isolation and did not exhibit her works, nor did she participate in public discussions of that time. . . . [I] am not even sure she saw her paintings as art works.” Though Voss amply demonstrates that af Klint did not paint in isolation—her work was carried out in the context of one spiritualist community or another—and that she actively sought to exhibit her work to her fellow spiritualists, it’s equally clear that af Klint did not consider her images merely “art,” and she never sought to present them to an “artworld public.” Rather, what she sought in vain for thirty years was a public of like-minded co-religionists. And when she couldn’t find that, she “hurled her work into the future,” trusting that at some point, that audience would exist.

What would Hilma af Klint of 1944 have made of her popularity today? Would she have been gratified by the attention and pleased by the crowds pouring in to enjoy her colorful, energetic abstractions? Or would she have been disappointed to see her revelations transformed into “art”? When Kandinsky, the ostensible originator of abstraction, accused most people of “disembarking at Regensburg” he was castigating the shortsightedness of those who prized naturalistic representation as the aim of art, thus failing to understand that the real destination of art was “Berlin”—the unleashed power and intrinsic spirituality of pure color, shape, and line, untethered from any representational burden.

While superficially Kandinsky and af Klint are both abstract painters, for Kandinsky and his art world, the painting was the end in itself. Not so for Hilma af Klint. I wonder if she would not have seen Kandinsky and all of us today, who mistake the image as the end of art rather than the otherworldly vision it reveals, as the ones disembarking at Regensburg.

Lisa J. DeBoer teaches the history of art at Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California. She is the author of The Visual Arts in the Worshiping Church (Eerdmans, 2016), which was awarded the Arlin G. Meyer Prize for academic non-fiction by the Lilly Fellows Program in the Arts and Humanities.