Ernest L. Boyer’s vision for Christian higher education is on the verge of collapse

When people I meet learn that I teach at Messiah University they often have questions: “What kind of school is Messiah?” “Is it anything like Liberty University?” “Is it a Bible school?” “Why do you teach there?” When I get these questions I remind my inquisitors that all Christian colleges are not the same. And then I invoke Ernie Boyer.

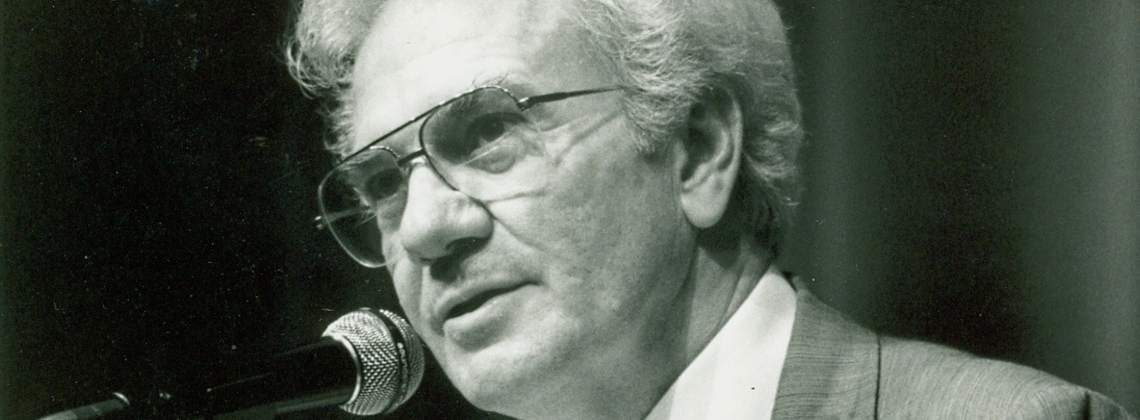

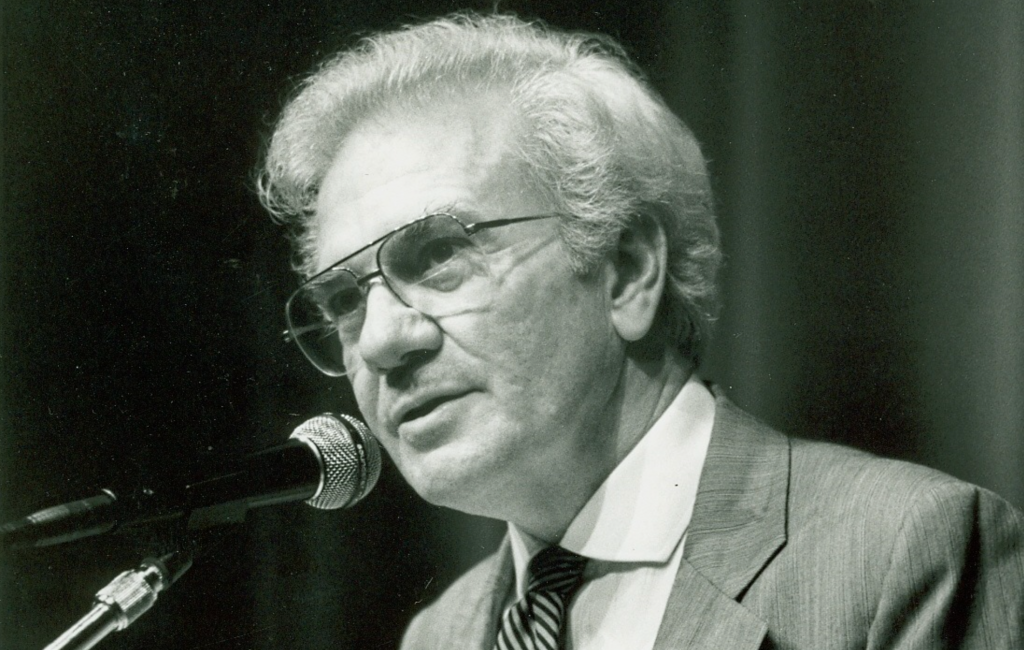

Ernest L. Boyer (1928-1995) was one the twentieth-century’s great educators. Over the course of his career he served as the first executive dean and second chancellor of the State University of New York (SUNY) system. He was Jimmy Carter’s U.S. Commissioner of Education (before the cabinet position Secretary of Education was created), and the president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. He is also Messiah University’s most distinguished graduate. On weekdays during the academic year you can often find me in my office on the second floor of Boyer Hall.

Boyer’s work focused heavily on providing education for the economically disadvantaged, creating national service programs that offered opportunities for students to do meaningful work in their communities, and promoting general education programs that helped students connect their schoolwork to their lives after graduation. Much of his educational vision stemmed from his upbringing in the Brethren in Christ, a Protestant denomination rooted in the Anabaptist, Pietist, and Wesleyan traditions. (Dwight D. Eisenhower is the most famous American with a connection to the Brethren in Christ Church.)

While much of his career was spent in the secular world, Boyer was deeply interested in Christian higher education. In his 1984 Messiah College convocation speech, “Retaining the Legacy of Messiah College,” he expounded on his vision for church-related colleges and universities. Boyer identified four virtues that “shaped the quality and character of Messiah College,” but added that “in each regard countless colleges and universities across America would be well served by following the model so effectively engaged on this campus.” Much of his work on this front is worth considering today, especially for those of us who teach in faith-based schools.

First, Boyer called for a robust liberal arts curriculum, one that cultivates “connectedness” across disciplines. “Unity, not fragmentation,” Boyer wrote, “must be the aim of education, and most especially what one calls Christian education.” He added: “In the Christian worldview the so-called secular and sacred are distinctions without meaning since all truth should ultimately be considered sacred.” A Christian liberal arts college is not a Bible college or a place where students only focus on specialized skills. It is rather a place where a serious general education curriculum offers students a breadth of knowledge about the world and their place within it. If God is the source of all truth and beauty, then the study of science, history, psychology, sociology, anthropology, literature, art, philosophy, politics, and language are all ways of exploring God’s created order and ultimately worshiping Him. There are no subjects or ideas of which to fear.

Second, Boyer argued that community is an essential part of a Christian college experience. College is a place where students learn how to be dependent upon one another—where education is less about individual ambition and more about learning and growing into what John Henry Newman once described as a “congregation of intellect.” Students should pursue their education, and ultimately, their callings, in conversation with educators, staff, and, of course, their fellow students. “If education is to exercise a moral force in society,” Boyer wrote, “the process must take place in a moral context. It must occur in communities that are held together not by pressure or coercion, not by the accident of history, but by shared purposes and goals, by simple acts of kindness, and by the respect group members have for one another.”

Third, Boyer believed that teaching is at the center of Christian college identity. Such institutions provide opportunities for excellent and engaging classroom discussion coupled with opportunities to build relationships—even friendships—with professors and mentors. This is what Boyer called the “human spirit” in the classroom. While the administration should encourage faculty to conduct research in their chosen disciplines, teaching is always central to the academic life of a Christian college or university. In fact, Boyer defined “scholarship” in a broad enough way to include pedagogy (“the scholarship of teaching”) in both formal academic settings and beyond the classroom.

Fourth, Boyer wanted students to find “connections between what they learn and how they live.” The cultivation of the mind is essential to Christian learning, but Boyer reminded us that good Christian thinking always leads to service. “It is urgently important,” he wrote, “that students seek connections between the classroom and the needs of people. . . . The tragedy of life is to die with convictions undeclared, and service unfulfilled.” Today, when Messiah University graduates walk across the stage at their graduation ceremony they receive a diploma and towel. Jesus washed the feet of his disciples and alumni of a Christian university should pursue similar forms of humble and selfless service to the people they will meet in the world.

Whenever I talk to students about Boyer’s vision of a Christian college or university we wonder together whether it is still viable today. What happens to the liberal arts, and the connectedness that such disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning offers, in an age when small colleges need more and more specialized majors to keep the doors open? How is community cultivated on campus in an age of online learning, in which many colleges have become accredited diploma mills with programs created for the purpose of making a quick buck? How have courses on ZOOM or course offerings with very little student-to-student or faculty-to-student interaction hurt college teaching? How do colleges connect service—a mantra in higher education these days—with deeply liberal, humanistic learning? What happens when faculty prepared to keep such questions alive retire, and in their stead come more professional programs or new and expensive sports teams?

I realize there are a lot of good thinkers out there trying to address these questions. But one wonders just how long Boyer’s vision will last. Places like Messiah University, and church-related schools like it, are trying to hold the line, but we live in a society where market demand drives everything. Liberal and humanistic education—the pursuit of the true, the good, and the beautiful—always contributes to a thriving and flourishing community, whether in a democracy or a church. But too often first things get swallowed up by personal ambition and economic acquisitiveness, the kinds of passions that serve and sustain our capitalist economy.

I wonder what Ernie Boyer would think about it all.

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current

During my 2018 spring sabbatical, I read and studied many of Ernest Boyer’s works. His four “scholarships” captivated my attention as they resonated with my educator’s value of teaching, interdisciplinarity, and connectedness. In addition to traditional disciplinary scholarship (what he calls “scholarship of discovery”), he offers the scholarship of teaching and learning (known as SoTL), the scholarship of integration (interdisciplinary learning), and the scholarship of application (connectedness to life-what we think of as the professions). The PowerPoint linked here from Eastern University adds digital scholarship, an area which we cannot ignore. As I ponder John Fea’s question here about whether Ernie’s vision will last and what Ernie would say, I would offer several thoughts. First, though inroads have been made at many small liberal arts colleges (and even others), the three types of scholarship beyond the traditional “scholarship of discovery” have not produced substantial changes in the reward structures and resource priorities of most colleges and universities. I advocate for a renewed focus on teaching and learning to enhance the other types of scholarships, not to compete with them. Second, while interdisciplinary majors and departments have increased, skepticism remains about their value, and they often end up as a choice for those who simply never settled on a chosen major and need to graduate. Let’s rethink interdisciplinarity as a fresh way of examining the world, its peoples, and our understanding of how to be and work in a global society. What if the disciplinary boundaries are more permeable than we have realized? Christians especially have a mandate to consider this since we believe that God created the cosmos in Christ, and it is united through Christ and the triune God as creator. Finally, with respect to the “scholarship of application”, or applied work (including the professions), I suggest we creatively investigate new ways to understand these pursuits as complementary to and not in conflict with traditional liberal arts. The synergy experienced in a vibrant, integral, connected course of study that weaves animating questions from the traditions with powerful ideas and issues we face today, all undertaken in a living community of learners, has the potential to reinvigorate both student and faculty. A carefully designed and intentional “core curriculum” can accomplish this while preparing students to work in the world in all aspects of their callings. Let’s go!