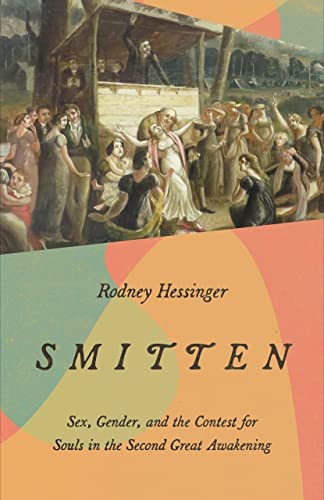

Rodney Hessinger is Professor of History and Associate Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences at John Carroll University. This interview is based on his new book, Smitten: Sex, Gender, and the Contest for Souls in the Second Great Awakening (Cornell University Press, 2022).

JF: What led you to write Smitten?

RH: I had long been fascinated by the social and religious experimentation yielded by the Second Great Awakening in early nineteenth-century America. This was a time when some groups were introducing polygamy, while others were adopting communal marriage. Yet others were committing followers to complete celibacy. This bold spirit was not just limited to new religious movements, such as the Shakers and Mormons, but also more mainstream churches such as the Baptists and Methodists. In such larger denominations, there was no disavowal of monogamy, but there was a serious reshuffling of gender expectations, with women being given much greater attention and even authority in shaping religion.

When I first discovered the “Hogan Schism” in the Catholic Church in Philadelphia, witnessing some of the same gender dynamics symptomatic of evangelical religion and new religious movements, I knew a larger story had to be told. I wanted to look together at how “new religious movements” and established churches had been thrown on the same field of competition during the Second Great Awakening. All were forced to make concessions to the desires of the people as a means to win new followers. Looking to court converts, they preached to the heart. They also opened their own hearts to dramatic new revelations, producing radical new forms of gender and sexuality. I wanted to show how enthusiastic religion could reshape society, not just play Durkheim’s function of “society worship.”

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Smitten?

RH: Competition during the Second Great Awakening encouraged churches to experiment with the ways they courted converts, including introducing innovations in sex and gender practices. Smitten reveals the sexual disruptions of religious enthusiasm, revealing also how a subsequent backlash domesticated religion in nineteenth-century America.

JF: Why do we need to read Smitten?

RH: At least since the publication of Whitney Cross’s The Burned-Over District in 1950, the Second Great Awakening has held the attention of American historians. While my book focuses particularly on sex and gender dynamics, ultimately I want to tell a larger story about the rise and fall of religious enthusiasm. As backlash swelled in response to sex and gender disorder, churches had important choices to make. Should religion accommodate and even sacralize the status quo? Or should it follow inspiration to challenge and change wider society? Those groups who were most committed to preserving their unique visions were often forced to find sanctuary in isolation. I want people to reflect on the way modern churches navigate these same types of choices and tensions.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

RH: I was converted (pun intended) to American history by my late mentor, C. Dallett Hemphill. Just recently, I had the distinct pleasure of helping bring her final book, Philadelphia Stories: People and Places in Early America to print. I had my first history class with Dallett in my freshman year of college. At the time, I had every intention of majoring in political science and going on to be a lawyer. But I discovered that the debates were so much more vital, and the purview of inquiry so much broader, in my history classes. By the time I graduated, I had been smitten with American history. I went on to graduate school at Temple University and have never looked back.

JF: What is your next project?

RH: I want to study the perception of religious prophecy as a symptom of madness. In studying John Humphrey Noyes, the founder of the Oneida commune, I noticed how he tried to clear himself of sexual scandal by distancing himself from the Philadelphia free-love prophet Theophilus Gates. Noyes insisted that Gates was deranged, a rhetoric I found that religious skeptics had leveled at Noyes himself. This episode tugs at larger questions: when one “hears voices,” how does society decide whether to view it as inspiration or insanity?

JF: Thanks, Rodney!