Writing on the day (December 5) that marks the ratification of the 21st Amendment in 1933, political scientist Mark Lawrence Schrad wants us to think about what the movement to end the manufacture, transportation and sale of liquor in the United States accomplished. In a piece at Politico he asks us to “remember that the war against alcohol was ultimately a war against political corruption and unbridled capitalism.”

Here is a taste:

In reality, the key to understanding prohibition is to recognize that temperance advocates of a century ago were not fighting against alcohol — the liquid in a bottle — per se. Instead, they hoped to destroy “the liquor traffic:” the predatory booze manufacturers and unregulated saloons that made money hand over fist from the drunken misery, addiction and pauperism of their customers. As historian K. Austin Kerr noted, the most important prohibitionist group was called “the Anti-Saloon League, not the Anti-Liquor or Anti-Beer League.” It was the unregulated, profit-maximizing trade that was the problem, not the booze itself.

This isn’t semantic sleight-of-hand or coy revisionism — prohibitionists were very clear about their goals. In introducing a prohibition amendment to the Constitution in 1914, Texas Sen. Morris Sheppard plainly said: “I am fighting the liquor traffic. I am against the saloon, I am not in any sense aiming to prevent the personal use of drink.” This is the reason why the 18th Amendment doesn’t forbid consuming alcohol, but rather “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” — the focus was the traffic.

So judging prohibition by personal-consumption statistics misses the point. A more reasonable comparison would be between the “liquor traffic” before and after prohibition — and it was objectively awful before prohibition.

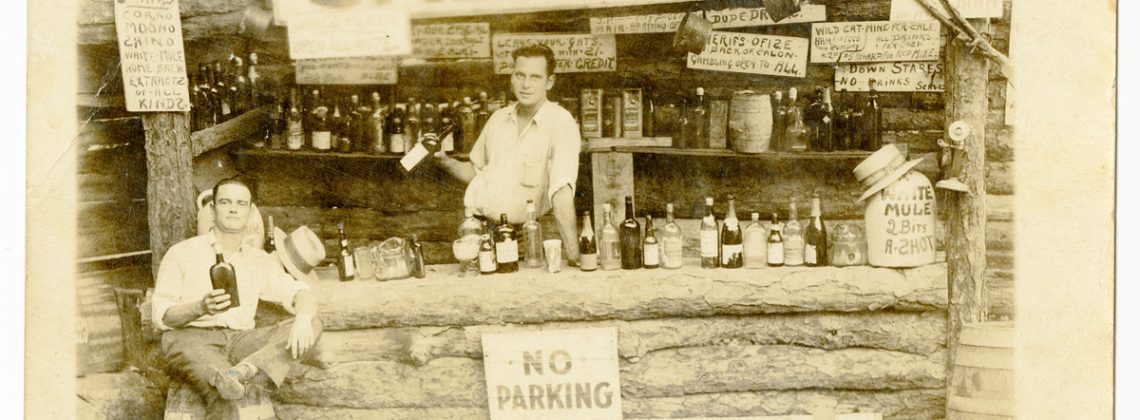

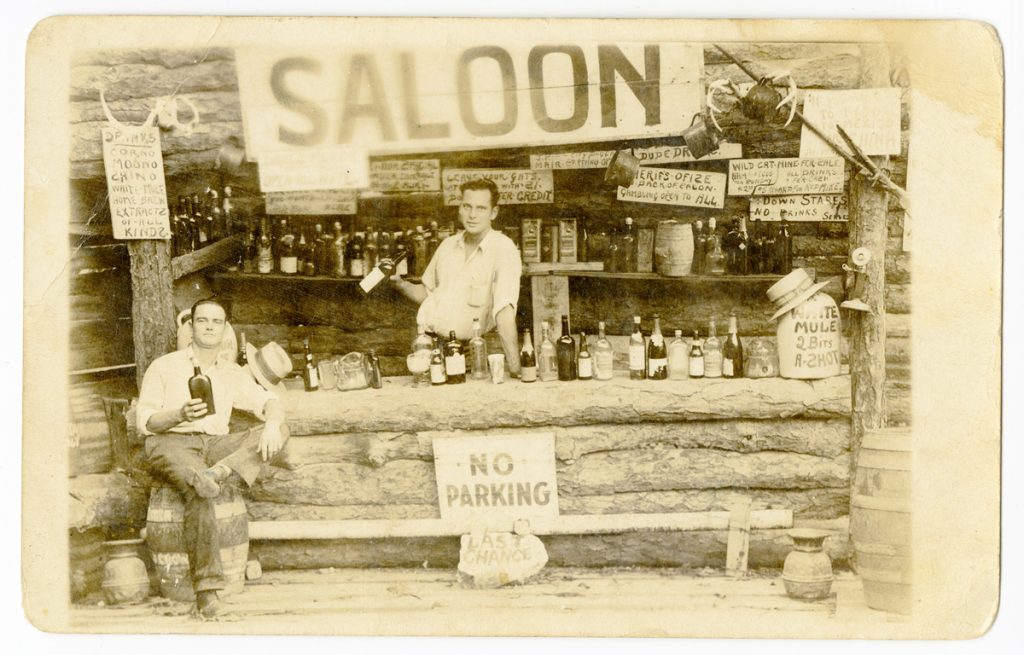

Nowadays, the word “saloon” evokes nostalgic Wild West motifs: cowboys, spittoons and swinging doors. But in reality, the saloon was the scourge of the local community. The saloonkeeper was not your friend, he was there to make as much money off you as possible. A drunkard sent home was profit lost. Better to keep an addict all night until his last penny was spent, and then sell him more on credit, barter or pawn, so that he remains in your debt. Many saloonkeepers also trafficked prostitutes upstairs and ran illegal gambling dens in back, while his pickpockets and grifters fleeced the drunks at the rail — and all with the corrupt acquiescence of police and politicians. The saloon wasn’t like Cheers and the saloonkeeper was no Sam Malone.

This is why the oft-parroted claim that prohibition caused organized crime and political corruption — while wagging a finger at Al Capone — is shortsighted to say the least. In the 19th century, every community large and small had their own Tammany Hall-style corrupt political machines, and everywhere the liquor traffic was at its core. Ironically, prohibition was envisioned as a way to purge liquor-traffic corruption from American governance, when what it did was just push it further underground.

For instance, when an aspiring young police commissioner named Theodore Roosevelt took on the corrupt New York liquor machine in 1894 — a generation before Capone — it was well-known that saloonkeepers could pay a bribe of $5 per month to sell booze illegally on Sundays, $25 to pimp out prostitutes and another $25 to run a gambling den. These tributes were collected by Tammany Hall gangsters, ward heelers and skull-crackers to be spread among the politicians. Every saloon contributed another $6.50 monthly to the Retail Liquor Dealer’s Association to buy off the local cops. Everyone was on the take. Everyone knew the game, especially since it was the saloonkeepers who got those politicians elected in the first place, by getting the men drunk to the hilt and marching them off to the polls to select the “correct” candidate, often multiple times over.

Or take The Jungle — Upton Sinclair’s classic muckraking novel of poverty and corruption in Chicago’s stockyards that prompted Roosevelt’s administration to sign both the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act (1906). Sinclair describes how on Election Day, hundreds of gangsters and ward heelers would go out from the saloons to deliver the required votes, “all with big wads of money in their pockets and free drinks at every saloon in the district. That was another thing, the men said — all the saloon-keepers had to . . . put up on demand, otherwise they could not do business on Sundays, nor have any gambling at all.” Sinclair was clear: In Chicago as in New York and American cities big and small, saloons were pure nests of political corruption.

What was true of the corruption of local politics was replicated at the state and national levels. A 1904 grand jury investigation found that the New York State Liquor Dealer’s Association wielded a sizable slush fund to keep state legislators “in good humor.”

Read the entire piece here.