The liberal order Green advocates has never been particularly liberal. It requires measured resistance.

With Rondall Reynoso’s essay we begin a series of responses to Jay Green’s feature published on Monday, November 28: “The New Shape of Christian Public Discourse.” Reynoso, a professor at Lee University, responded to the original version of Green’s essay, a paper delivered at the annual Lee Symposium this past October. What follows is a modified version of that response.

*

The last time Jay Green and I interacted professionally was at the 2014 biennial of the Conference of Faith and History, where he moderated a panel in which I presented a paper entitled “Artists, Art Historians, Nudity, and the Evangelical Audience.” So how did the art & religion guy get invited to be a respondent in a forum on Christian public intellectual discourse?

At Lee University we take seriously the idea of “calling,” even if varying members of our community nuance the concept differently. In my capstone class I often tell students, all of whom are art majors, that I don’t view my calling as specifically art but more broadly as promoting human flourishing. In this I honor my Thomistic training and approach it through the transcendentals of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful, all of which I engage personally and vocationally.

Growing out of these commitments, I run a website called Faith on View where we write and share news, commentary, and essays. We have a consonance with Current; however, we tend to exist on the center-left while I see Current as occupying the center-right. Or to use the proposed formulation, we would be Emancipatory Maximalists while Current is Emancipatory Minimalists. So while in the proposed system we may not be as problematic as the Civilizational Maximalist (a.k.a. Trumpism or Christian nationalists), we are, for Green, nonetheless problematic.

First, I would like to affirm the importance of this discussion. The liberal-conservative binary is increasingly unhelpful, and it is good to see efforts to further nuance these discussions. This binary has felt creaky my entire life.

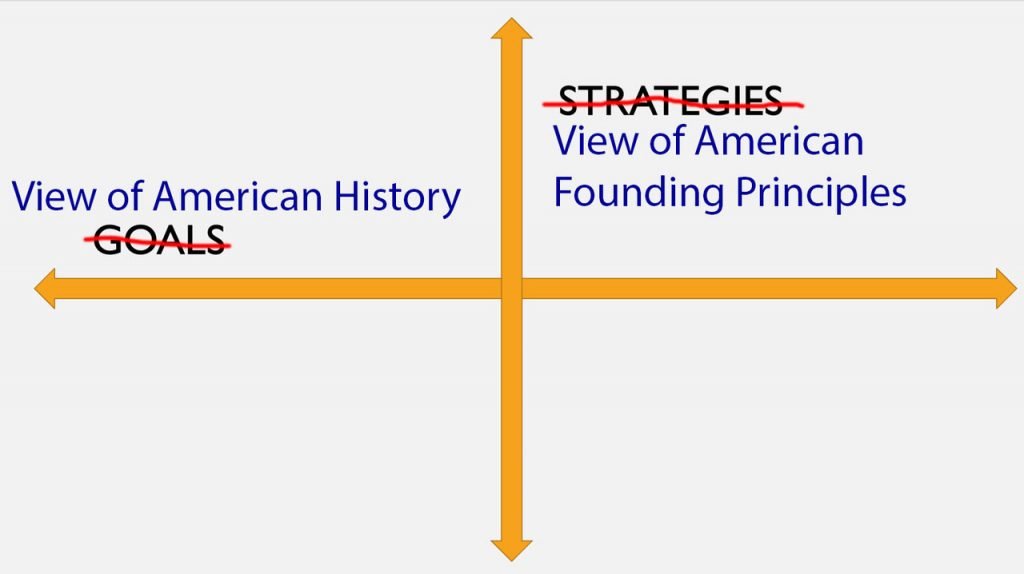

For me, one of the failings of the proposed mapping is that, while it provides relatively nuanced distinctions of perspectives that would typically be labeled conservative, it does not do the same for those positions that would be considered liberal or progressive. The vast majority of Never Trumpers would map onto the Emancipatory Minimalist section, putting them diametrically opposed to Trumpism, which is located in the Civilizational Maximalist region. Likewise, the traditional conservative perspective of Civilizational Minimalists maps opposite of all progressives, who are categorized as Emancipatory Maximalists. This formulation creates greater nuance for conservative perspectives but fails to provide illumination for any ideological stances that are not considered conservative.

The x-axis purports to represent the ends and the y-axis the means. The Civilizationist side seeks to establish a Christian society while the Emancipationist side wants an America that provides “liberation and harmony among all people.”.

However, the heart of Green’s discussion about the x-axis centers on one’s view of history rather than one’s aspirations for our nation. The Civilizationists believe that our “once proud country” has been “hijacked,” while the Emancipationist believes that “[s]ocial and structural hurdles planted in America’s past . . . [function] as barriers to human flourishing.” These two seem inexorably connected. However, the distinguishing element actually centers on one’s view of American history rather than the goal of developing a Christian nation. Should America strive to reclaim the Edenic ethos of the American founding? Or should it seek to remake this nation that “historically disadvantaged and systematically marginalized” entire peoples? Does the United States boast a long-term trajectory moving toward “expanding civil rights and liberties”? Or are the “values of this American civilization . . . endangered” and in need of “renewing” and “revitalizing”?

Green presents the y-axis as a measure of “means.” But he also claims that for those in the Minimalist camp “[l]iberalism isn’t simply a means. It is also a goal.” With this statement he admits that the axial system he proposes does not in fact consist of one axis representing the goal and the other the means. He also claims that the gulf between the Maximalist and the Minimalist on the y-axis is broader than the distance between the Civilizationist and the Emancipationist positions on the x-axis. I, however, am not convinced that disagreements over the means are greater than the difference between those who imagine a mythical American history rooted in devotion to God and those who see the founding of America as a bigoted, genocidal, colonial, power grab rotten from its foundation. Possibly the chasm between the Civilizational Maximalist and the Emancipatory Minimalist seems so great to some because prior to 2016 they believed each other to be in unity, or at the least allied.

I tend to see Green’s vertical axis not as a reflection of means but rather of attitudes toward American founding principles, with liberal democracy on the bottom and authoritarianism on the top. This seems to be less an axial system where individuals can float anywhere along the x- or y-axis and more of a U-shaped continuum moving from the Alt-Right in the upper right, to the traditional conservative below that, to the moderate conservative on the bottom left, and finally to the top left where all forms of progressivism reside. It reminds me of a system suggested by Adam Joyce, who is critical of both conservative centrists and liberal centrists for prioritizing “a sanctified process of politics over seeking liberation and justice”—a very Emancipatory Maximalist statement. For Joyce, this commitment to a process of politics is insufficient and eventually collapses into an “acquiescence to the oppressive status quo.” So clearly, Joyce would be a Maximalist in the construction here. This serves to underscores that this is not a dynamic axial system.

A U-shaped continuum, on the other hand, places the Civilizational Maximalists and the Emancipatory Maximalists at the two extremes. This makes sense: the Alt-Right, Christian Nationalists on one side with the progressives and most of the Democratic party on the other. There really is very little if any movement along the x-axis between these two without dipping into the bottom half of our map.

From my perspective, the discussion of Emancipatory Maximalists is the most problematic part of this conceptual mapping, since it collapses all nuance on the left into one small quadrant. I began this response by calling myself an Emancipatory Maximalist. I did so not because I reject the liberal order but because its advocates often distort it into something it never was.

For example, he sees free markets as a tenant of the liberal order apparently on the same level as free speech and individual rights. Yet the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes, while part of the liberal tradition and affirming of free markets, have long been castigated as socialistic redistribution of wealth by the right’s political messaging. We limit the liberal economic tradition to “classical” or Smithian economics but distort it into something Adam Smith would not recognize. Smith was critical of corporations in the eighteenth century, and he likely would be today. His Invisible Hand relied on an open market with no barriers to entry, no individual seller or buyer large enough to move prices, and truthfulness of information across markets. Smith also warned against “People of the same trade . . . [committing] a conspiracy against the public . . . to raise prices.” When it comes to stockbrokers and those who make their living off the markets, he warned that they are people “whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have.” In today’s system, these foundational conditions of the free market require regulation to maintain.

Further, Smith believed that taxation was not theft and that the citizenry “ought to contribute towards the support of the government . . . in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state.” This protection included not just defense but also justice, which he defined, in part, as “protecting, as far as possible, every member of the society from the injustice or oppression of every other member of it.” Smith also believed that some public works “are always better maintained by a local or provincial revenue, under the management of a local and provincial administration.” Taxes, he believed, should also cover public institutions, such as education, and even the “Dignity of the Sovereign.”

This Smithian conception of free markets is at odds with current conceptions and explains why we struggle to understand that Washington and Jefferson were comfortable with Virginia being able to set prices on private transactions such as the price of an inn. Or how Thomas Paine could propose a universal basic income as a matter of justice, arguing that “rich” and “poor” are arbitrary rather than divine divisions.

Green accuses Emancipatory Maximalists of abandoning the “procedural niceties of liberalism in exchange for a hardened vision of identity politics.” Are we referencing procedural niceties such as dumping tea into the Boston harbor or the burning of Peggy Stewart? True, these were a part of the civil unrest leading to the Revolutionary War. But they were spurred by liberal ideals. Once in power, most Founding Fathers rejected such civil unrest (excepting Jefferson, who stood alone in this perspective). While most in power rejected such behavior, that does not change the history of the fight for civil rights, which often turned violent under liberal ideals both prior to the founding and after. Further, was the hardened identity politics of the abolitionist movement or of women’s suffrage at odds with “the procedural niceties of liberalism”? Or the identity politics of the civil rights movement? Or the farm workers movement?

I can’t shake the feeling that if this system were applied to ancient Israel many of the prophets who saw the brokenness in Israel and eschewed the niceties of discourse would fall in the Emancipatory Maximalist quadrant.

In a policy analysis for the Cato Institute, political scientist Patrick Porter reminds us that the twentieth-century liberal order was never free of the vulgarities of Realpolitik. Our Pollyanna nostalgia for the liberal order creates a “fictitious and demanding historical standard . . . A pernicious byproduct of such nostalgia is reductionism.” Further, “Endless recall of the ‘liberal order’ is not only ahistorical. It is harmful.” The y-axis in this system seems to further this mythology.

I affirm the liberal principles of civil discourse, open inquiry, open debate, free speech, tolerance of difference, the illuminating power of dissent, the hope of reform through persuasion and compromise, fairness, due process, individual rights, and the free market (so long as we don’t polemicize it to exclude Keynesian ideas or even Adam Smith). Yet I believe we tend to romanticize liberal principles and mold them into something very different.

From my perspective, Kristin Kobes Du Mez, Jemar Tisby, and Beth Allison Barr all fit within the liberal tradition. I would add to the list Robert Chao Romero, author of Brown Church. Their devotion to justice for particular identities through civil discourse and the illuminating power of dissent does not put them at odds with the liberal tradition but instead squarely within it. The conception of “traditional liberalism” in this system is too small.

Most concerning to me, though, is the conflation of the liberal tradition with Christianity. To bind Christianity to an Enlightenment philosophical construct is, from my perspective, dangerous. Is there consonance between liberalism and Christianity? I can accept that. I can even accept the suggestion of considerable consonance. The explicit Minimalist claim, however, is that “liberalism is a basic tenet of Christianity itself.” That is too far. Our political and moral philosophies should be informed by our faith. If done well there will be great consonance between the two. But they are not the same. Refusal to affirm the tenets of liberal political philosophy does not equal denial of the suffering savior who laid down His life for humanity.

The discourse of Christian intellectuals in the United States today should be relevant to American public discourse. But it should at the same time transcend our national identity. Christianity and Christian political engagement existed before the advent of liberalism or our nation.

Both of these axes are rooted in one’s relationship to the United States. The x-axis is tied to one’s understanding of American History. Is the U.S. a righteous nation blessed by God? Or is it an abomination built on oppression and murder? Or is it somewhere on the spectrum between? The y-axis reflects one’s commitment to founding American ideals—the rejection or acceptance of liberalism. These axes neither transcend our national identity nor are rooted in our faith.

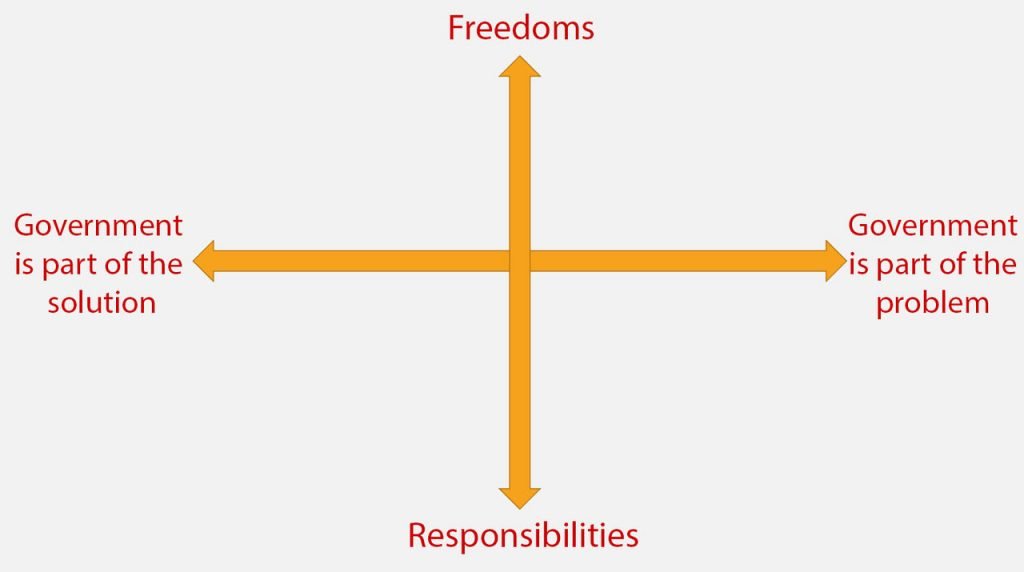

Let me briefly propose alternate axes that I believe transcend our national identity, are rooted in our faith, and that provide a lens that can illuminate our circumstance while remaining fundamentally distinct from the left-right binary.

Consider an x-axis representing the spectrum of our dispositions toward government. On the far left, government is seen as good, even a sacred tool provided by God. On the far right, government is bad, the problem not the solution, a broken immoral tool.

Then consider a y-axis that charts our focus. Those on the top are focused on their freedoms and the individual good; those at the bottom are focused on the individual’s responsibility to others, the common good. Let me suggest that those on the bottom left who view government as a tool for good and are focused on their responsibility to the common good have, whether liberal or conservative, a great deal in common. Likewise, those on the top right who are focused on their individual good and view government as bad and broken, while seemingly at the most radical ends of a left-right spectrum, are very similar. Both are ready to burn it all down in pursuit of their individual good.

Thankfully, my project here is not to explore this proposal in more detail and open myself up to what I am sure are obvious flaws. Still, there may be virtue in totally reimagining how we approach our political discourse.

Rondall Reynoso is an artist, scholar, and Assistant Professor at Lee University exploring the confluence of the good, the true, and the beautiful. He is also the founder and Executive Editor at Faith on View.

What a learned, thoughtful, and thought-provoking response. I hope _Current_ will remind us in advance when the Lee Symposium is coming around again so that we can consider attending it – I am starting to suspect that Lee University most be a leading venue for a robust, Christian intellectual culture in higher education.

Thanks, Tim. We were happy to post it.

As for Lee University, I had a great experience there several years ago as a speaker at this symposium. There is a nice community of Christian thinkers in the Chattanooga area.

Timothy,

Thank you for your kind words. The Lee Symposium is in October every year and does provide for some great discussions. Lee University like everywhere has its strengths and weaknesses but for me the symposium is an annual highlight.

Rondall