“Seeing that these young ones have enough to eat is a great hindrance to one’s reading.”

In Book Marks, an occasional feature at Current, we take fresh cuttings from old books (or about old books). They may be about writing, education, communication, and the life of the mind generally, though we reserve the right to snap a sprig of greenery that simply tickles the fancy.

Why look at old books? Because there’s a slat loose in the fence they’ve got us penned up in, and we can jiggle it free to see better what’s going on out there.

With each extended quotation we offer an orienting comment, but that’s not where the action is. The question is whether the words of those who have gone before may speak to you.

*

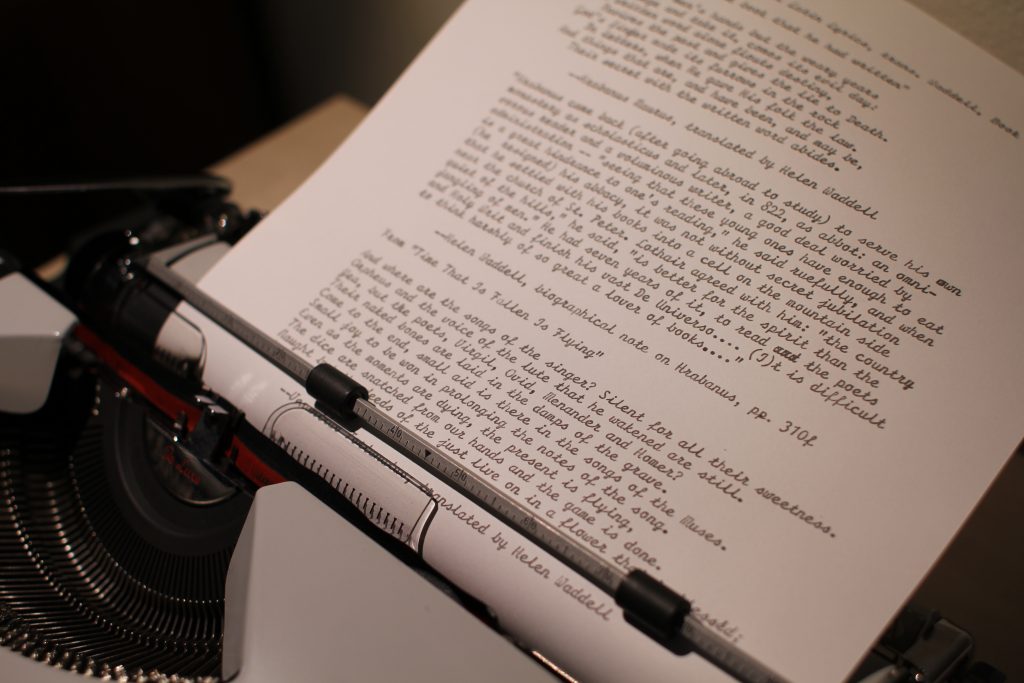

The Japanese-born Irish poet Helen Waddell published a bilingual volume of medieval Latin lyric poetry during the years between the World Wars that gives us flashes of insight into how precious books were before the movable-type printing press—while at the same time demonstrating how bibliophilia is actually pretty timeless.

The first poem below congratulates a colleague on his book launch (well, maybe that’s putting it anachronistically . . . ). By the way, have you reached out to an author lately to thank them for their work? Doing so can give great satisfaction all around.

My Latin isn’t nearly good enough to comment on whether Waddell’s poems are faithful translations—but they certainly are faithful to the love of books and the complicated feelings they engender.

Hear what she has to say:

“To Eigilus, on the book that he had written,” by Hrabanus Maurus (776–856 CE)

No work of men’s hands but the weary years

Besiege and take it, comes its evil day:

The written word alone flouts destiny,

Revives the past and gives the lie to Death.

God’s finger made its furrows in the rock

In letters, when He gave His folk the law.

And things that are, and have been, and may be,

Their secret with the written word abides.

Waddell’s biographical note on Hrabanus contains further charming book notes:

Hrabanus came back [from studying abroad] to serve his own monastery as scholasticus and later, in 822, as abbot: an omnivorous reader and a voluminous writer, a good deal worried by administration—”seeing that these young ones have enough to eat is a great hindrance to one’s reading,” he said ruefully, and when [he resigned] his abbacy, it was not without secret jubilation that he settled with his books into a cell on the mountain side. . . . Lothair agreed with him: “the country quiet of the hills,” he said, “is better for the spirit than the jangling of men.” He had seven years of it, to read the poets and Holy Writ and finish his vast De Universo. . . . [I]t is difficult to think harshly of so great a lover of books. . . .

.But another poem in Waddell’s collection takes a somewhat opposing point of view:

From “Time That Is Fallen Is Flying,” by Venantius Fortunatus (c. 530–c. 603 CE)

And where are the songs of the singer? Silent for all their sweetness.

Orpheus and the voice of the lute that he wakened are still.

Yea, but the poets, Virgil, Ovid, Menander and Homer?

Their naked bones are laid in the damps of the grave.

Come to the end, small aid is there in the songs of the Muses.

Small joy to be won in prolonging the notes of the song.

Even as the moments are dying, the present is flying,

The dice are snatched from our hands and the game is done.

Naught but the deeds of the just live on in a flower that is blessèd;

Sweetness comes from the grave where a good man lieth dead.

—Helen Waddell, trans., Mediæval Latin Lyrics (1929; repr. New York: W. W. Norton, 1977), pp. 107, 310f, and 67

*

Jon Boyd is keeper of Book Marks at Current. He is associate publisher and academic editorial director at InterVarsity Press, the saxophonist in an improvisational rock band, a user of mechanical typewriters and postage stamps, and (with his wife and daughters) a resident of the City of Chicago.