Our default optimism runs counter to our deepest wisdom

When a book’s title proclaims what already should be obvious, we probably should drop everything and figure out the misunderstanding that requires us to be told this thing again. A full review of MIT philosopher Kieran Setiya’s Life Is Hard: How Philosophy Can Help Us Find Our Way deserves more reflection on its own terms than this moment, with crises on every side, may allow. But our moment needs this book.

Setiya’s insight echoes an old story that made the rounds in the vicinity of MIT a couple hundred years ago, when a student at 1600s Harvard recorded something remarkable that he heard from the college president. This is the story, in the student’s own words: a nurse was holding a baby who suddenly “spake these words, (This is an hard world.): the nurse when she had recovered herselfe a little from her trembling, & amazement at the Extrardinariness of the thing, said, Why deare child, thou hast not known it: the Child after a pause, replied, But it will be an hard world & you shall know it.”

I get a laugh out of that story every time. The baby gets credit for noticing early what we all figure out. Now, one could argue that a sunny outlook—it’s morning in America, don’t sweat the small stuff—sets a person up for success. But when we rosily assume Life is Good®, hard things come as a rude surprise. When we take for granted that normal life is comfortable and predictable, optimizable and shareable on Instagram, we are underprepared for adversity.

If we instead get up in the morning assuming the day will be hard in ways known and unpredictable, with the likelihood of loss, and frustration with self and our efforts at things—things that have to be gotten through, things that won’t be fun but have to be done anyway, and all of this shadowed by the givenness of mortality: Then we are in better shape to meet what comes. We know that life is much harder for some people than others, wealth insulating many shocks. But all are prone to frailty and mortality.

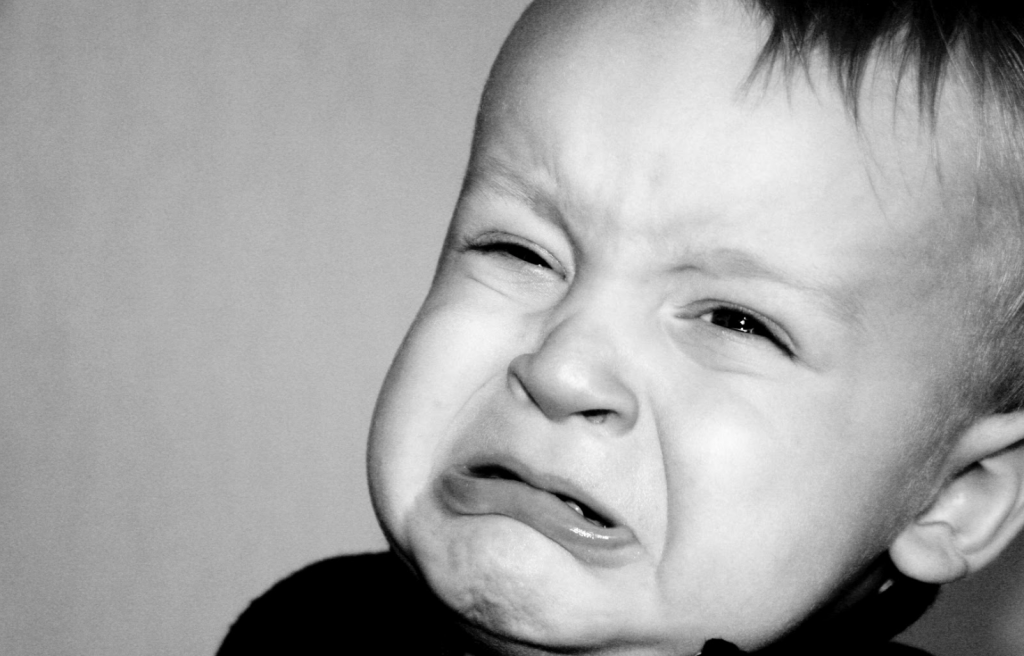

To say that life is hard does not mean it isn’t also good, rich, and worth having. The world is full of beauty and living can bring joy, but—and the baby will back me up here—just being can be hard. Life is hard not just in the sense that awful things happen, tragedies and monstrosities. They do, but the problem is more basic than that. Since wisdom occasionally comes from the mouth of babes, look to another one for an apt metaphor: a baby crying on an airplane. That’s the feeling—both of the baby and of the guy the next seat over, added together. Life is hard.

One problem with our default optimism is that when trouble comes, our common stock of language to address hardship is poor. People say things like: Don’t fret, it could be worse; don’t fret, somebody else has it even worse; don’t fret, you were never promised a rose garden; don’t fret, everything will turn out for the best; don’t fret, whatever doesn’t kill will make you stronger. The first fails by relativizing goods, sprinkling pixie dust to persuade that one ugly thing is beautiful because it sits next to a wartier toad. The second is cruel, buying our peace at the price of another’s misery. Worse, that comparative calculus of suffering tempts us to normalize disaster rather than railing, lamenting, or preventing. The third counsel convicts one of an entitlement that few really claim; most people really don’t expect all ease or to win every prize but hope, rather, that fish and bread reach our needy hands rather than snakes and stones.

Finally, the command to interpret bad things as good ones is a despicable transvaluation. It might come prettied up piously—that God works all things for the good or that suffering produces character. It does, or at least can. But a prosperity-gospel gloss—everything for a reason and pearls built from grit—claims more wisdom than it possesses. That confidence clangs like a favorite guidance-office slogan, “Easy Now, Hard Later. Hard Now, Easy Later.” If only it were so. It is nice when putting in work early situates us more comfortably later on. Most of the time the reward for doing the hard thing now is more hard things later.

Recognition that life is hard is better than weightless words of cheer. Recognition is no denial of the good of being alive. Even when we cannot resolve the hurts we identify, recognizing them offers a kind of solidarity. Setiya writes, “What we need in our affliction is acknowledgement.”

All this may sound dour. Why not look on the bright side? In fact, presupposing hardship adds value. First, knowing that life is hard makes us disinclined to make it harder, freeing us to say no to the many stupid things that market or fashion might want to impose. Second, and much more important, this mindset nurtures compassion. After all, efforts to make our own lives easier often depend on foisting difficulty on someone else, or something or someplace else. Admitting the strain of things for ourselves can give insight into the plight of others. We know that different things are hard for different people, so we might wonder what is hard for our neighbor. Even without any action, that pondering would do timely service. Imagine over the next week what would be accomplished by assuming life is hard for the guy in the next seat or lane of traffic or across the aisle. Of course we also should act on that idea. When we are aware of another’s struggle, we might learn what to do to bear with or stand alongside them. Setiya agrees: “Reflecting honestly on affliction in our own lives leads toward concern for others, not into more self-regard.”

Revisit that precocious baby. New England ministers passed around the story as a “remarkable providence,” which meant they saw something in it out of the ordinary. What made the story remarkable, and for us funny, is not that the too-young baby spoke or that the baby knew a truth crystal clear to older people, but that the woman holding the baby acted like she didn’t know. What is remarkable is that some need to be told again.

Agnes R. Howard teaches in Christ College, the honors college at Valparaiso University, and is author of Showing: What Pregnancy Tells Us about Being Human.

I am reminded of Christina Rossetti’s poem, “Uphill”

I will check it out. Thanks for the recommendation.