Here is historian Bennett Parten at Zocalo Public Square:

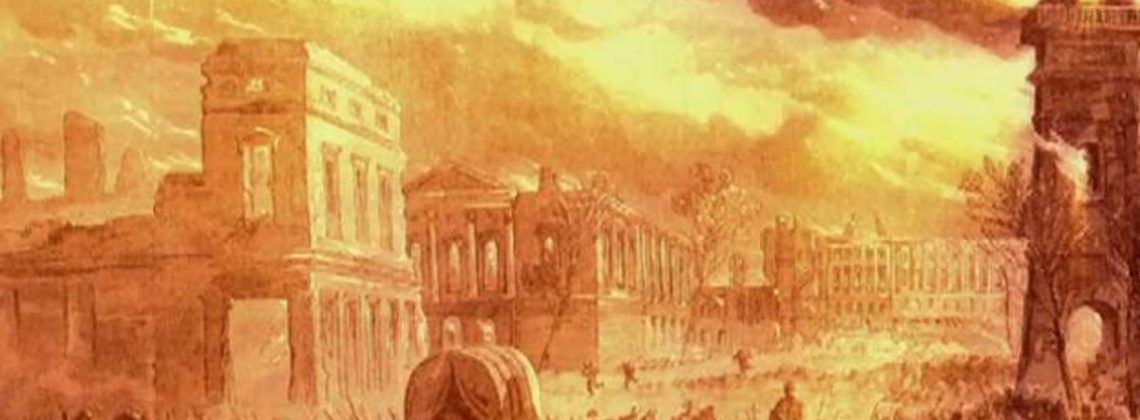

Americans get Sherman’s March all wrong. Ask anyone who’s seen Gone with the Wind, and they’ll tell you that U.S. General William T. Sherman’s roughly 250-mile march from Atlanta to Savannah marked the swan song of the Confederacy. They’ll recall the burning of Atlanta, a panoramic scene in the film that made cinematic history, and they’ll regard Sherman as most Georgians still do, as the man who laid waste to the state by slashing and burning his way to the coast.

But this story of fire and arms obscures an arguably more important story: Sherman’s famous March doubled as the largest emancipation event in American history, accomplishing on the ground what Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation could do only on paper. It broke the back of the planter class, destroyed Confederate morale, and legitimized the freedom of thousands. And it’s here, deep in Georgia, along a slow-moving body of water known as Ebenezer Creek, where the American case for reparations began. This oft-forgotten origin story is one of the lasting legacies of Sherman’s great March, even if it’s also perhaps the least understood.

From the moment Sherman moved his men out of Atlanta in November 1864, enslaved people fled plantations to meet the soldiers—arriving day and night, as families or as lone escapees. Some made long, circuitous journeys. Others met the marchers right in front of large plantation homes. All acted as a force that propelled Sherman’s army forward. They pointed the way to hidden plantation treasures; they directed soldiers down clandestine footpaths through the woods; they supplied Sherman and his scouting parties with critical pieces of military intelligence. Formerly enslaved people also worked for the army as cooks, valets, or pioneers (a military term for road builders or ditch diggers). Some even lined the roadsides and cheered on the army as it marched past.

Many of the formerly enslaved people who ran to the army went a step further: They decided to follow the army, as refugees, in an effort to make their freedom more secure. Freed refugees had attached themselves to federal armies in other theaters of war but never on a scale such as this. Sherman would later speculate that by the time his army arrived in Savannah, as many as 20,000 freed refugees from slavery followed in its wake; many thousands more may have marched along before turning back somewhere along the way. If true, this number is astounding: 20,000 nearly matched the pre-war population of Savannah, antebellum Georgia’s largest city.

Read the rest here.