Here is a taste of Katha Pollit’s recent piece at Dissent:

On the other hand, if you have open elections, with a free press and organized political parties that can compete on equal terms with the governing party, people can vote socialism out. That’s what happened in Nicaragua in 1990 and seems to be happening today with Sweden, Denmark, France, and other countries where socialist parties were once powerful. Indeed, the social democratic welfare states we admire have been shrinking for years. Sweden has downsized its social provisions to the point that the New York Times blamed cutbacks for a “wave of death” in nursing homes during the pandemic. (As we went to press, the far-right Sweden Democrats appeared likely to become the largest party in a new right-wing governing coalition, threatening to undo decades of progressive social policy.) Moreover, hostility to immigration is moving formerly progressive voters rightward all over the social democratic world. Denmark is now one of Europe’s most hostile places for immigrants—and the social democrats are as bad on that issue as the xenophobic People’s Party. Democracy doesn’t always work to the greater good.

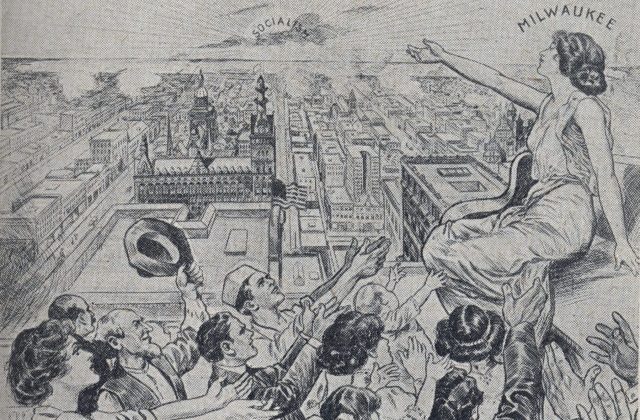

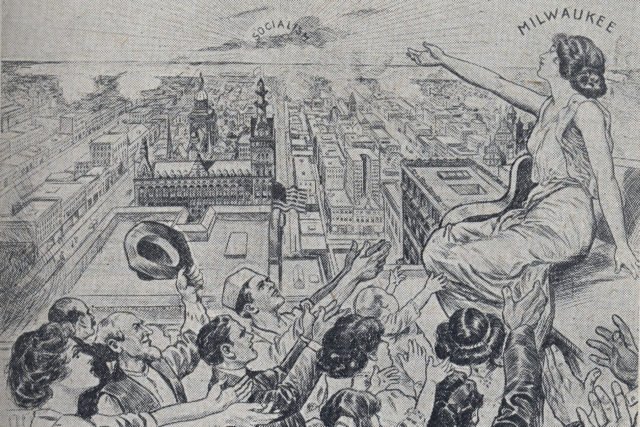

Contemporary socialists spend a lot of energy denying the relevance of self-described socialist states or the capitalist welfare states of Western Europe: they weren’t really socialist. But if those countries weren’t socialist, what does that say about the socialist idea itself? At best one has moments and glimpses—the “sewer socialism” of Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Red Vienna and Red Bologna; Kerala in India. Perhaps it is a bit like Christianity, whose believers attribute to it everything good it has done and whose detractors blame it for everything bad it has done, while nobody can actually point to a society that embodies it.

Capitalism is clearly hurtling us toward many kinds of disaster, foremost of all global warming. It’s hard to see how a system based on profit and ever-increasing consumption can safeguard natural resources at the same time it needs to exploit them to the full. People are right to reject a system based on that contradiction, and to demand an end to extreme and increasing inequality; the ill-paid labor of millions of workers, especially immigrants; and the unacknowledged and unpaid labor and subjection of women. They are right, too, to feel disenchanted with an electoral system that gives outsize power to major donors and caters to the self-interest of the rich and almost rich, and which the Republican Party is doing its best to turn into a Hungarian-style authoritarian democracy with a bit of theocracy thrown in.

Without some kind of urgent mass movement, it is hard to see how we’ll get out of the hole that’s being dug for us. And for a mass movement you need hope. I don’t feel particularly hopeful these days, but socialism is my name for the hope I still sometimes feel that we can share wealth and power and knowledge, be less selfish and cruel, and let everyone, not just the lucky few, develop their talents and have a good life. Maybe individual freedom and the common good don’t have to be opposites. How can that happen? Someone else will have to figure that out.

Read Pollit’s entire piece: “My Name for Hope”