Here is the University of Houston historian at his Insider Higher Ed blog:

No longer does the “simple advice to high schoolers to ‘go to college’” suffice. What one studies and where one studies matter greatly in terms of return on investment. Which degrees earn the most? No surprise: computers, math, health-care practice, architecture, engineering and business.

Which leaves the liberal arts, and especially the humanities, where?

If, for most students, the primary measure of an undergraduate degree is return on investment, shouldn’t our institutions double down on those high-demand, high-return fields and let the liberal arts shrink to an appropriate size?

I don’t think so.

The most distinctive feature of American higher education is the value it places on liberal education. Nor is this simply a legacy of a more elitist education in the past. Even as American colleges and universities broadened their curricula during the 19th century and embraced electives toward the end of that era, these institutions gradually and unevenly adopted gen ed requirements to ensure that all undergraduates achieved the rudiments of a liberal education.

Why did they do that? To ensure that all students acquired transferable soft skills? In part. To cultivate culturally literate graduates? In small measure. The primary purpose was more ambitious: to nurture a certain kind of person—observant, reflective, sensitive and thoughtful, but also someone who is an independent thinker.

In his account of the biblical story of Joseph and his sale into slavery by his brothers, Flavius Josephus, the Romano-Jewish historian, wrote that the captive’s Egyptian master “held him in all honor and gave him the education that befits a free man.”

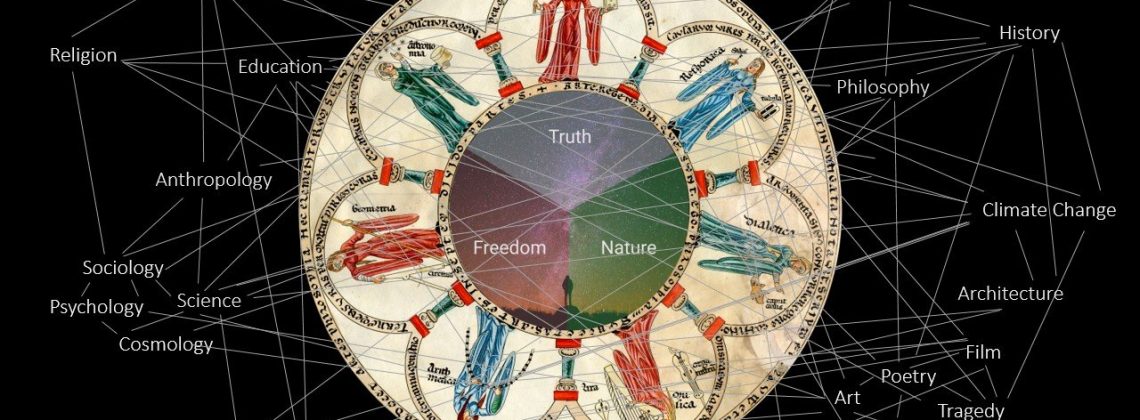

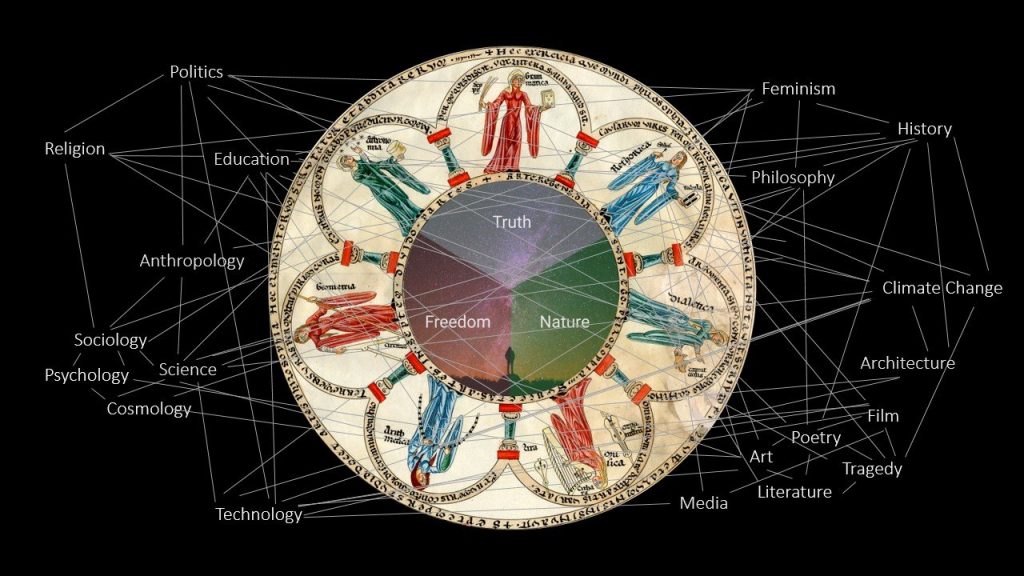

That phrase—“the education that befits a free man”—has become a synonym for a liberal education—an education that combines breadth and depth, that cultivates a capacity to engage rigorously and critically with the major issues of the day, appreciate culture in its multiple manifestations, and serve as the essential foundation for informed citizenship.

The piece also answers these questions:

- In theory, general education requirements are supposed to guarantee that all undergraduates receive a truly liberal, rounded and robust education. But do they really?

- Should we be concerned If most undergraduates do not receive that kind of a liberal education?

- Was John Dewey right: Is liberal education in practice, if not in theory, class and culture bound, backward-looking and excessively abstract?

- Should the champions of a liberal education defend it on instrumental grounds—that it provides the kind of transferable soft skills necessary in a volatile society—or on some other basis?

Read the entire piece here.