Our plight and our salvation are one

Agrarian Spirit: Cultivating Faith, Community, and the Land by Norman Wirzba. University of Notre Dame Press, 2022. 264 pp., $29

There are multiple books on the philosophy and history of American agrarianism, but Norman Wirzba provides—for the first time—a comprehensive “spirituality” of agrarian consciousness. Wirzba, the Gilbert T. Rowe Distinguished Professor of Christian Theology at Duke Divinity School, uses the work of Wendell Berry to show how a reverence for place and all its inhabitants might play out in everyday practice.

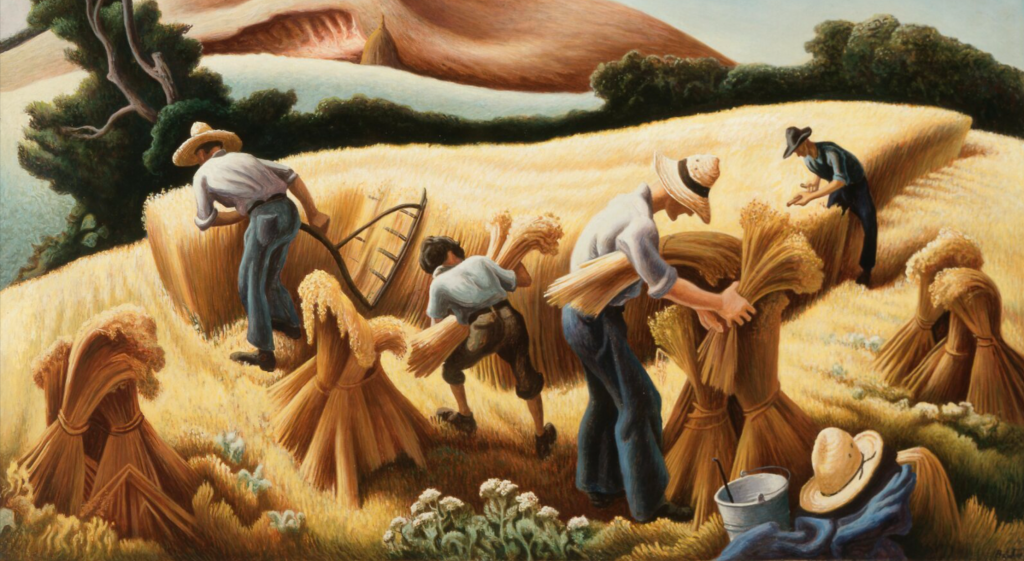

The “agrarian spirit” is about so much more than farming. It’s the way we eat, work, pray, connect, and move through the world in view of the interlocking web of soils, plants, waterways, and animals that live alongside us. It has to do with how we pay attention in a culture given to the objectifying and commodifying of everything. It asks how we express gratitude for the ways our lives are supported by myriad beings—from microorganisms inside our gut to field workers sending food to our tables.

An agrarian sensitivity insists that we are what we are only in relationship to each other. No one stands alone. To live in an interdependent world is first of all “to unseat oneself as the center or focus of the universe.”

Agrarianism, however, has often been associated with a back-to-the-land nostalgia—the naïve notion that a life of rural simplicity is inherently moral. At the University of Missouri in the early nineteenth century, for example, students who had grown up on a farm were automatically excused from having to take the required course in moral ethics.

This nostalgia was part of the Southern Agrarianism that flourished at Vanderbilt University in the 1930s. Authors like John Crowe Ransom and Robert Penn Warren celebrated the “Southern Way of Life,” styling themselves “fugitives” from the prevailing banality of modern, urban, industrialized existence. Unfortunately, their work was tinged by the myth of the Lost Cause of the American confederacy.

Aldo Leopold, on the other hand, urged a “land ethic” based not on nostalgia but on the inherent importance of every life form within an ecosystem. We can’t “suppose that breakfast comes from the grocery or heat from the furnace,” he urged, but must instead attend to the value of every part in the unfolding process.

Wirzba’s contribution is to ask what spiritual disciplines are necessary for living a life that exercises such attentiveness. He argues from Maximus the Confessor that God is always seeking to express God’s embodiment, in the whole of creation as well as the incarnation. This means that no creature is complete in itself. Our work is to see God’s love and vitality embedded in every thread of the tapestry of our lives. Ours is to stand in awe at the mutual interdependence we share, rejecting the “habit of contention” that has too often pitted us against the world, each other, and ourselves.

At the heart of this contemplative practice is what Wendell Berry describes as the mystery of the “membership” one shares in a community where roots are honored and connections maintained. Take the intertwining membership of Berry’s fictional town of Port William, Kentucky. Its members include colorful characters like Burley Coulter, as well as draft horses, river traffic, the town barber, even bacteria in the compost pile.

Burley can sit as evening comes in the hollow of an old sycamore, pondering a world so entwined that even his own being isn’t his own. “We are members of each other,” he exclaims. “All of us. Everything. The difference ain’t in who is a member and who is not, but in who knows it and who don’t.” This awareness of palpable connection to the world we occupy is a hunger shared increasingly by people today. Growing out of the displaced character of contemporary life, it’s far more than an exclusively rural phenomenon.

In Berry’s short story “Fidelity,” Burley is dying of old age. His nephew Danny takes him to the hospital, thinking something ought to be done to help him with what he’s going through. But when the medical staff connects him to machines and starts running tests, Danny knows he’s made a terrible mistake. He and his friends end up “kidnapping” the old man and taking him to a familiar hollow where he can die in peace. He rests there as a light rain falls and the place receives him. “It was as though the woods had stopped whatever it was doing to regard him as he entered, had permitted itself to be distracted by him and his burden and his task, and now that he had ceased to move it went back to its unfinished preoccupations.”

This sense of belonging to a place and being embraced by its mystery is a spiritual sensitivity endemic to the human soul. We need to be nested, to own our kinship with the earth. But in a time of severe climate change and socio-environmental crisis, this ethic is just as important for the planet. Norman Wirzba’s book comes at the right moment, pointing us to the shared vulnerability—the deep interconnectedness—that is at the same time our plight and our salvation.

Belden Lane is Professor Emeritus of Theological Studies at Saint Louis University. His books include The Solace of Fierce Landscapes and The Great Conversation: Nature and the Care of the Soul.