What I learned about the evangelical embrace of Trump from watching old news clips

I spent the better part of my summer watching television news broadcasts from the first decade of the twenty-first century. My current research project on evangelicals and politics in America required me to conduct research at Vanderbilt University’s Television News Archive, a video collection of evening newscasts that aired on NBC, CBS, ABC, CNN, and Fox. It was a pleasure watching television reruns instead of trying to decipher eighteenth-century handwriting. And it only took me a few weeks to get the voices of Dan Rather, Tom Brokaw, Peter Jennings, Anderson Cooper, Aaron Brown, Judy Woodruff, and Shepherd Smith out of my head.

Since my research was focused on the years between 1999 and 2008, all the stories I viewed covered news that happened during my adult life. I remembered most of them. Yet watching evangelicals fight the culture war at the turn of the century with the hindsight of what happened to the movement during the Trump years led me to see new things and ask new questions.

Historians always approach the past from where they sit in the present. Our contemporary milieu shapes the questions we ask of our subjects. Though the present does little to help us understand what happened in the past—we need to encounter the past on its own terms, not ours—the historian is always working to bridge time.

I came away from my experience in Nashville with a sense of just how much has changed in the first two decades of this century. Sometimes 1999 felt like 1899. For example, in 2004 nearly all the Democratic candidates for president believed marriage is a union between a man and a woman. Many leading evangelicals believed Mitt Romney was unfit to serve as President of the United States because he was a Mormon. One could find members of the Republican Party who defended a woman’s right to choose. Richard Cizik, the vice-president of the National Association of Evangelicals, almost lost his job when he suggested that evangelicals should address climate change.

I watched Christian Right leaders criticize Bill Clinton for his failures of character during the impeachment trial. I observed Southern Baptist spokesperson Richard Land explain to CBS News’s Byron Pitts why evangelicals would not support the 2007 presidential candidacy of former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani: “He’s in his third marriage. White evangelicals are much more tolerant of divorce than they used to be, but three wives is one too many for most evangelical voters.” These jeremiads on presidential character take on new meaning when examined from the so-called “Age of Trump.” As I argued in Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump, these same spiritual leaders defended one of the most morally flawed presidents in American history in 2016. Did the moral standards that the Christian Right expected of its leaders in the late 1990s and 2007 change over time? Or were they just a bunch of hypocrites who had one set of moral standards for Democrats and another for Republicans? So many questions.

But at the same time, I also saw signs of continuity between the past and the present during my research. Now that I look back from my seat in the present I am able to draw direct lines between evangelical engagement in 1999 and evangelical engagement in 2022.

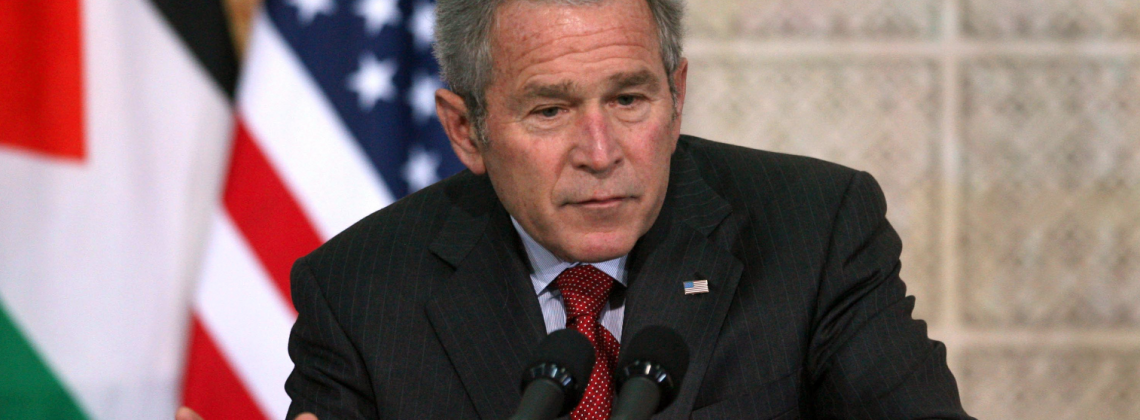

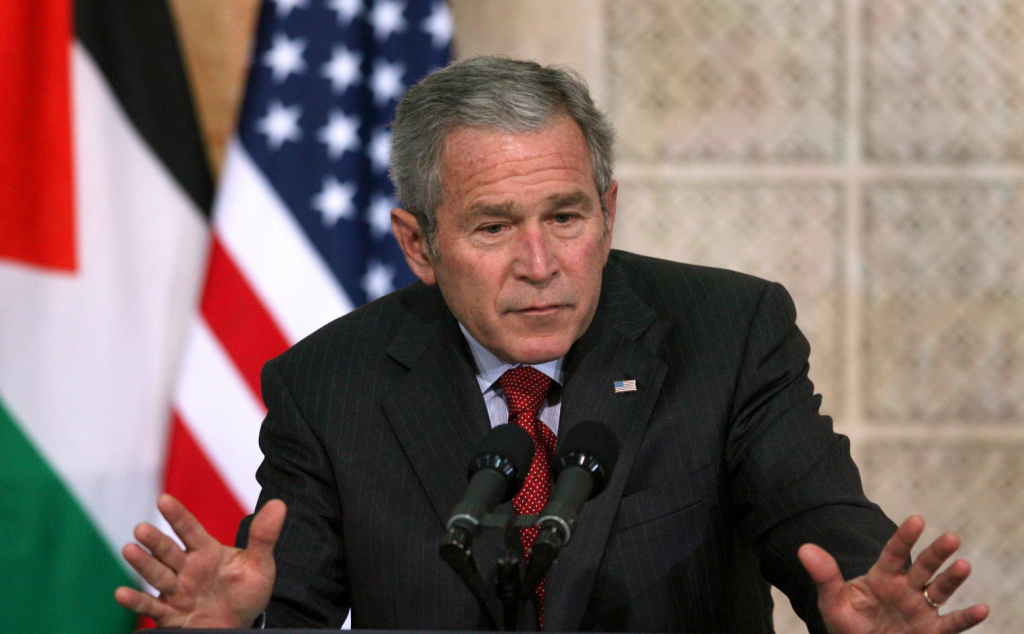

For example, there were a lot of stories in the early 2000s about evangelical support for Israel. While president George W. Bush pushed for an independent Palestine (the so-called “Two-State Solution”), 700 Club host and Christian Coalition president Pat Robertson opposed him at every turn and did so as a regular guest on network and cable news shows. John Hagee also opposed Bush’s Israel policy. The San Antonio megachurch pastor believed that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank was a harbinger of the return of Jesus Christ. When Hagee founded “Christians United for Israel” in 2006, Christian Right leaders and politicians such as 2000 presidential candidate Gary Bauer, Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum, and House Majority Leader Tom DeLay attended his annual conferences. One of the goals of this organization was to move the American embassy to Jerusalem. In 2017, President Donald Trump gave Robertson, Hagee, and the rest of the prophecy-obsessed Christian Right their wish.

There was also Bush’s 2005 nomination of Harriett Miers to the Supreme Court. Miers was the White House Counsel and an old family friend of the president, but she had no experience on the bench. When Bush nominated her to replace Sandra Day O’Connor, the Christian Right panicked. Because Miers had no judicial record and once said that she believed in a woman’s right to privacy, the Christian Right openly opposed her nomination. Miers was too risky. Some recalled how Reagan nominees O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy failed to deliver on decisions important to the Christian Right. They could not vet Miers because there was very little to vet. They preferred a candidate with a proven track record of dissent in abortion-rights cases. After Bush withdrew Miers’ nomination, he turned to Samuel Alito, a federal judge with the right track record on abortion. During his run for president in 2016, Trump relieved the anxiety of his Christian Right supporters by publishing a list of Federal Society-approved, pro-life judges he would appoint to the bench if elected. There would be no Harriet Miers fiascos with Trump in office, and conservative evangelicals showed their appreciation in the ballot box.

In the 2008 campaign and throughout his presidency roughly one-third of white evangelicals believed Barack Obama was a secret Muslim despite his repeated claims that he was a Christian. This lie about Obama’s religious faith, which was peddled by conservative media sources and e-mail chains, set the stage for Trump’s attacks against the “fake news” aired by the so-called “liberal media.” The transition from “Obama is a Muslim” to “what you’re seeing is not what’s happening” was seamless. Social media only exacerbated these conspiracy theories.

The more I watched the short segments and the talking heads on television news at the turn of the century the more I saw the roots of what was to come. When Trump proclaimed on the campaign trail and during his presidency that “We will be saying Merry Christmas again,” he tapped into the “War on Christmas” first waged on Fox News and other conservative outlets nearly twenty years earlier.·

The Christian Right’s response to the 2005 Dover, Pennsylvania controversy over the teaching of “Intelligent Design” in public school classrooms foreshadowed the conservative evangelical distrust of scientific experts we witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic. By the spring of 2020, evangelical anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers were well-trained on how to question science.

We cannot make sense of conservative evangelicals’ support for Trump’s border wall and his draconian immigration policies without understanding how disappointed they were when Bush proposed an immigration reform plan that sought to lift undocumented immigrants “out of the shadows” and provide them with a path toward citizenship. Both Bush and 2008 GOP candidate John McCain failed to deliver on the nativist agenda of the Christian Right. Trump did.

Yes, the signs were there, but most of us did not notice them. This, of course, is why we have historians. They try to help us to see what we have missed. It is hard not to watch as much television news from the early 2000s as I have and not conclude that the evangelical embrace of Donald Trump was inevitable—the logical result of two decades of Christian Right political engagement.

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current

Thanks for your article. I’m currently reading American Psychosis: A Historical Investigation of How the Republican Party Went Crazy by David Corn. He makes the same point you’re making.

I’m interested merely in a clarification. You wrote, “By the spring of 2020, evangelical anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers were well-trained on how to question science.” This seems to suggest that evangelical anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers had learned the proper technique for questioning science. Did you mean that? It seems to me that they had learned to question science, but not how to question it legitimately or properly.

Yes, I can see how it could be read that way. I meant what you said in the last sentence.

Thanks for the recommendation, Alan.

Thank you for doing the research for us. Insightful essay.

There’s more to come, Mary! Thanks for reading!