Historian and former Harvard president Drew Gilpin Faust wonders how they will interpret the past. Here is a taste of her piece at The Atlantic:

Given a current generation of students in which so few can read or write cursive, one cannot assume it will ever again serve as an effective form of communication. I asked my students about the implications of what they had told me, focusing first on their experience as students. No, most of these history students admitted, they could not read manuscripts. If they were assigned a research paper, they sought subjects that relied only on published sources. One student reshaped his senior honors thesis for this purpose; another reported that she did not pursue her interest in Virginia Woolf for an assignment that would have involved reading Woolf’s handwritten letters. In the future, cursive will have to be taught to scholars the way Elizabethan secretary hand or paleography is today.

I continued questioning: Didn’t professors make handwritten comments on their papers and exams? Many of the students found these illegible. Sometimes they would ask a teacher to decipher the comments; more often they just ignored them. Most faculty, especially after the remote instruction of the pandemic, now grade online. But I wondered how many of my colleagues have been dutifully offering handwritten observations without any clue that they would never be read.

What about handwriting in your personal lives? I went on. One student reported that he had to ask his parents to “translate” handwritten letters from his grandparents. I asked the students if they made grocery lists, kept journals, or wrote thank-you or condolence letters. Almost all said yes. Almost all said they did so on laptops and phones or sometimes on paper in block letters. For many young people, “handwriting,” once essentially synonymous with cursive, has come to mean the painstaking printing they turn to when necessity dictates.

During my years as Harvard president, I regarded the handwritten note as a kind of superpower. I wrote hundreds of them and kept a pile of note cards in the upper-left-hand drawer of my desk. They provided a way to reach out and say: I am noticing you. This message of thanks or congratulations or sympathy comes not from some staff person or some machine but directly from me. I touched it and hope it touches you. Now I wonder how many recipients of these messages could not read them.

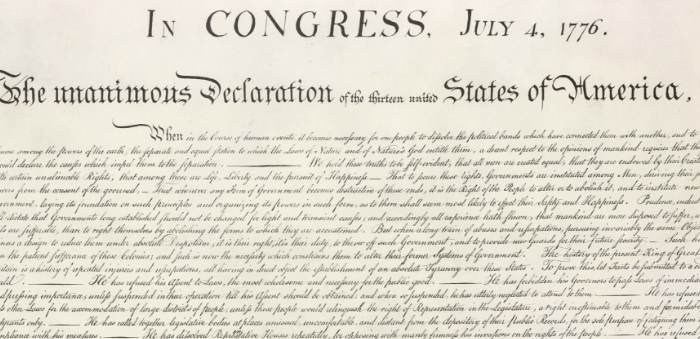

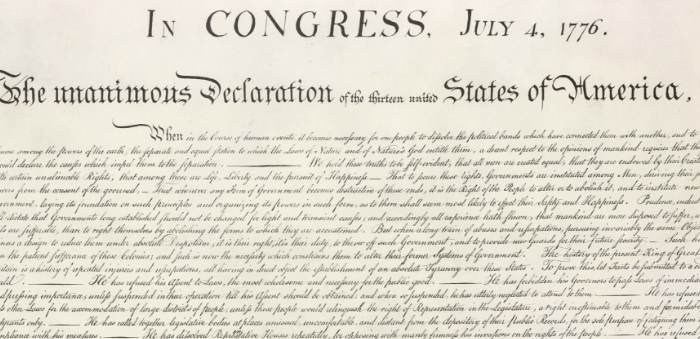

“There is something charming about receiving a handwritten note,” one student acknowledged. Did he mean charming like an antique curiosity? Charming in the sense of magical in its capacity to create physical connections between human minds? Charming as in establishing an aura of the original, the unique, and the authentic? Perhaps all of these. One’s handwriting is an expression, an offering of self. Crowds still throng athletes, politicians, and rock stars for autographs. We have not yet abandoned our attraction to handwriting as a representation of presence: George Washington, or Beyoncé, or David Ortiz wrote here!

There is a great deal of the past we are better off without, just as there is much to celebrate in the devices that have served as the vehicles of cursive’s demise. But there are dangers in cursive’s loss. Students will miss the excitement and inspiration that I have seen them experience as they interact with the physical embodiment of thoughts and ideas voiced by a person long since silenced by death. Handwriting can make the past seem almost alive in the present.

In the papers of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., I once found a small fragment with his scribbled name and his father’s address. Holmes had emphasized the significance of this small piece of paper by attaching it to a larger page with a longer note—also in his own hand—which he saved as a relic for posterity. He had written the words in 1862 on the battlefield of Antietam, where he had been wounded, he explained, and had pinned the paper to his uniform lest he become one of the Civil War’s countless Unknown.

Read the entire piece here.