“There are men still living who can recall the days when it was considered necessary and even delightful to write letters to one’s friends.”

In Book Marks, an occasional feature at Current, we take fresh cuttings from old books (or about old books). They may often be about books, writing, education, communication, and the life of the mind generally, though we reserve the right to snap a sprig of greenery that simply tickles the fancy.

Why look at old books? Because there’s a slat loose in the fence they’ve got us penned up in, and we can jiggle it free to see better what’s going on out there.

With each extended quotation we offer an orienting comment, but that’s not where the action is. The question is whether the words of those long dead may speak to you.

*

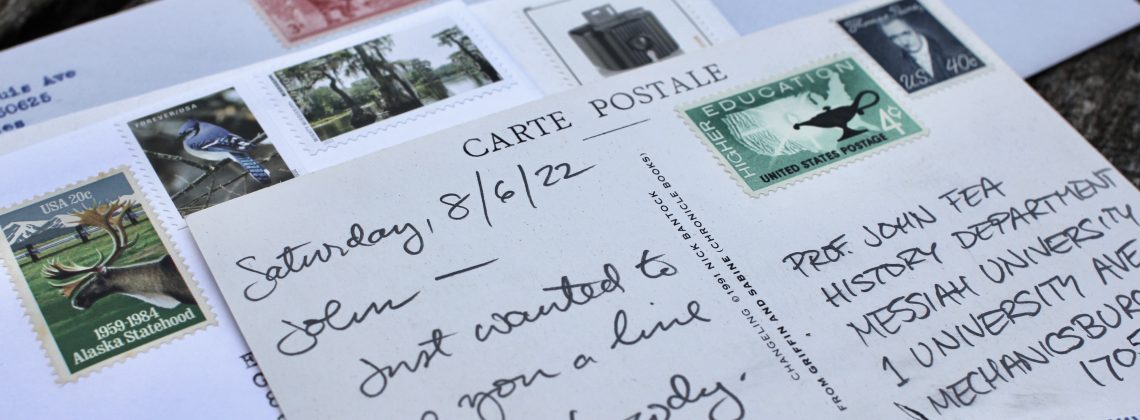

It’s hard to believe there was a time when picture postcards were high tech, a “gee whiz!” communications innovation—but many true things are hard to believe. We humans are just a little bad at assessing reality, especially when it comes to the past.

To be perfectly honest, I don’t recommend the book Adventures in London by James Douglas (1909) as much more than the equivalent of a blog a century before its time. But it is invaluable for conveying an in-the-moment view of what it was like to see personal correspondence transformed by the visual technology of the mass-produced postcard, which in the Anglophone world was only a decade or so old. We can’t take all Douglas says at face value, because he slips in and out of satire unreliably. But his punditry is no more off kilter than many a commentary today about Instagram or TikTok.

Hear what he has to say:

When the archæologists of the thirtieth century begin to excavate the ruins of London, they will fasten upon the Picture Postcard as the best guide to the spirit of the Edwardian Era. They will collect and collate thousands of these pieces of pasteboard, and they will reconstruct our age from the strange hieroglyphs and pictures that time has spared. For the Picture Postcard is a candid revelation of our pursuits and pastimes, our customs and costumes, our morals and manners. . . .

Like all great inventions, the Picture Postcard has wrought a silent revolution in our habits. It has secretly delivered us from the toil of letter-writing. There are men still living who can recall the days when it was considered necessary and even delightful to write letters to one’s friends. Those were times of leisure. . . . It is sad to think of the books which dead authors might have written if they had saved the hours which they squandered upon private correspondence. Happily, the Picture Postcard has relieved the modern author from this slavery. He can now use all his ink in the sacred task of adding volumes to the noble collection in the British Museum. Formerly, when a man went abroad he was forced to tear himself from the scenery in order to write laborious descriptions of it to his friends at home. Now he merely buys a Picture Postcard at each station, scribbles on it a few words in pencil, and posts it. This enhances the pleasures of travel. Many a man in the epistolary age could not face the terrors of the Grand Tour, for he knew that he would be obliged to spend most of his time in describing what he saw or ought to have seen. The Picture Postcard enables the most а indolent man to explore the wilds of Switzerland or Margate without perturbation.

Nobody need fear that there is any spot on the earth which is not depicted on this wonderful oblong. The photographer has photographed everything between the poles. He has snapshotted the earth. No mountain and no wave has evaded his omnipresent lens. The click of his shutter has been heard on every Alp and in every desert. He has hunted down every landscape and seascape on the globe. Every bird and every beast has been captured by the camera. It is impossible to gaze upon a ruin without finding a Picture Postcard of it at your elbow. Every pimple on the earth’s skin has been photographed, and wherever the human eye roves or roams it detects the self-conscious air of the reproduced. The aspect of novelty has been filched from the visible world. The earth is eye-worn. It is impossible to find anything which has not been frayed to a frazzle by photographers. . . .

There are still some ancient purists who regard Postcards as vulgar, fit only for tradesmen. I know ladies who would rather die rather than send a Postcard to a friend. They belong to the school which deems it rude to use abbreviations in a letter, and who consider it discourteous to write a numeral. The Postcard is, indeed, a very curt and unceremonious missive. It contains no endearing prefix or reassuring affix. It begins without a prelude and ends without an envoy. The Picture Postcard carries rudeness to the furthest extremity. There is no room for anything polite. [A]s a rule, there is no space for more than a gasp.

— James Douglas, “The Age of Postcards,” in Adventures in London (London: Cassell, 1909), 377–79

*

Jon Boyd is keeper of Book Marks at Current. He is associate publisher and academic editorial director at InterVarsity Press, the saxophonist in an improvisational rock band, a user of postage stamps and mechanical typewriters, and (with his wife and daughters) a resident of the City of Chicago.