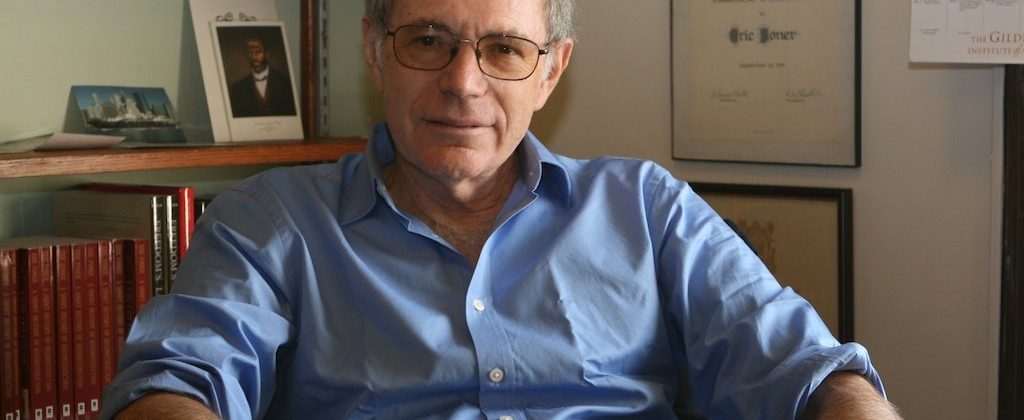

Eric Foner reflects on his life as a historian in this interview with Nawal Arjini at New York Review of Books. A taste:

Nawal Arjini: How did you come to specialize in Civil War history?

Eric Foner: When I was in college in the 1960s, I wanted to be a physics major, but I had a great deal of interest in history; my father and uncle were historians. The civil rights revolution was reaching its peak, and many young people like myself wanted to find out where this crisis came from. We had been taught a history that said the problems of American society had been solved, and yet here were thousands of people in the streets insisting that serious problems still existed.

I took a course on the Civil War era with James Shenton. Here’s the impact a teacher can have: I took that course, and I’ve been studying the period ever since. My first interest was the antislavery movement. My dissertation and first book were about how the early Republican Party, dedicated to stopping the expansion of slavery, rose to power, and how politics can be used to promote radical social change. Later I started studying Reconstruction. The debates in our society today about citizenship, the right to vote, terrorist violence in our country—that period raises all those issues. I’m always interested in the connections between past and present. The questions that interest me historically tend to come out of the moment I’m living in.

And now there’s a resurgence in the study of the post–Civil War era and the legacies of emancipation.

History never totally repeats itself, but there are a lot of similarities. Younger historians are now looking at why Reconstruction was not successful in solidifying the basic rights of African Americans. The Constitution was amended. The laws were changed. Equality was put into our social fabric for the first time. And yet then it was overthrown and reversed. How did that happen? Why is something like that happening today? Frederick Douglass said that progress is not necessarily inevitable. Rights can be gained and taken away.

Your father was a historian as well—one of many people who were blacklisted from teaching for decades on suspicion of being Communists. What impact did this have on your own life and your development as a historian, as well as on the discipline of history and teaching in general, especially on the left?

My father, Jack Foner, lost his job at the City University of New York because of the legislative investigation of “Communist influence” on the school. This was in the early 1940s, before McCarthy. My mother, who was a high school art teacher and an artist in her own right, was also named and was going to be fired from the city educational system, but the principal of her school allowed her to retire on a medical disability instead so that she could get a pension. My family lived on my mother’s pension while I was growing up. Much later, in the late 1960s, my father was able to get a teaching job for the remainder of his career.

Blacklisting had a devastating impact on the teaching of history. Some of the very best scholars were thrown out of the profession. But I eventually realized that that experience was very educational. I learned something a lot of my college classmates didn’t know and had to learn during the 1960s: the rhetoric of freedom, liberty, and progress in our country does not comport with reality. A person losing his livelihood because someone called him a Communist—what does that tell us about freedom of speech, academic freedom in this country? The principles the country claimed to stand for and the practices it instituted were contradictory, which many young people came to discover in other ways, through the Vietnam War and the way the government lied or the civil rights revolution and the idea that we lived in equality.

I also learned from my uncles Henry and Moe Foner. Henry was the head of the Fur and Leather Workers Union; Moe was a leading figure in the Drug and Hospital Workers Union. I learned by osmosis how important to democracy it is to have a vibrant labor movement. That’s one of the more recent problems of our democracy, the serious decline of the labor movement...

In some ways, history and historical research seem to be in the public consciousness more than ever. But in other ways, as you note in the piece, the field seems reduced beyond belief.

There’s a great deal of interest in history. Of course, it’s become a battleground in the culture wars, which I hope will go away soon. But the problem is that there is not enough history education. Bush and Obama are equally guilty. They based school funding on exam results in English and math, meaning history is a luxury that many schools can’t afford. Many states, including New York, have reduced the number of years that students are required to take history in school.

It’s tricky right now; because of economic insecurities, students will say, “If I major in history, what kind of job am I going to get?” I don’t think history can ever win that battle. We can’t accept the principle that the way to judge a course of study is by how much money you will make. It’s important to study history if you want to be an intelligent citizen in a democracy...

Could you talk a little bit about your experiences being mentored by the historians Richard Hofstadter and James Shenton?

Shenton was a brilliant, inspiring teacher. Hofstadter was actually pretty boring in lectures, though he was a brilliant writer. That’s what I learned from him: we have an obligation to write well so that we reach a broader audience. History is an act of the imagination.

I never had a female history teacher in college or graduate school. When women’s history came along, and then gender studies, I tried to incorporate those insights into my writing. After the so-called linguistic turn of the 1980s, I wrote a book about the history of the word “freedom” in America. It was my effort to see what I could take from the growing study of language as part of history. I always try to keep learning.

Read the entire interview here.