Here is Massimo Faggioli at Commonweal:

Legge 194 (or “The 194,” as Italians call it), which the Italian Parliament passed in 1978, allows women to receive abortions through the first ninety days of pregnancy, after getting counseling in a public medical facility. Beyond ninety days, abortion is permissible “a) when pregnancy or childbirth involves a serious danger to the woman’s life; b) when pathological processes are ascertained, including those relating to significant anomalies or malformations of the unborn child, which cause a serious danger to the physical or mental health of the woman.”

When there is the possibility of viability outside the womb, interruption of pregnancy is permissible only when pregnancy or childbirth involves a serious danger to the woman’s life, and then the doctor who performs the surgery must take all appropriate measures to safeguard the life of the fetus. Before Legge 194, a woman who had an abortion risked up to four years in prison, and whoever performed an abortion faced up to five years. “The 194” has survived constitutional challenges and even a public referendum in 1981; though it decriminalized abortion, it did not make it a constitutional right.

And this:

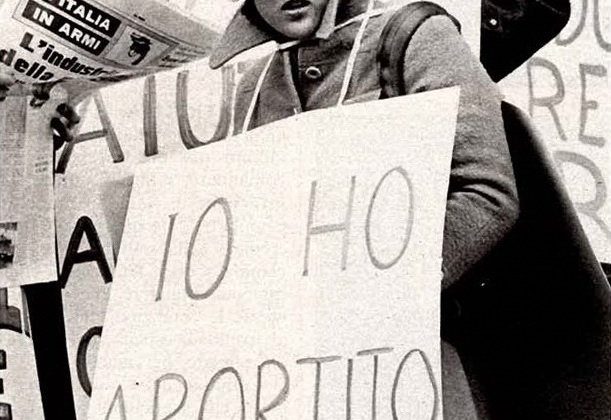

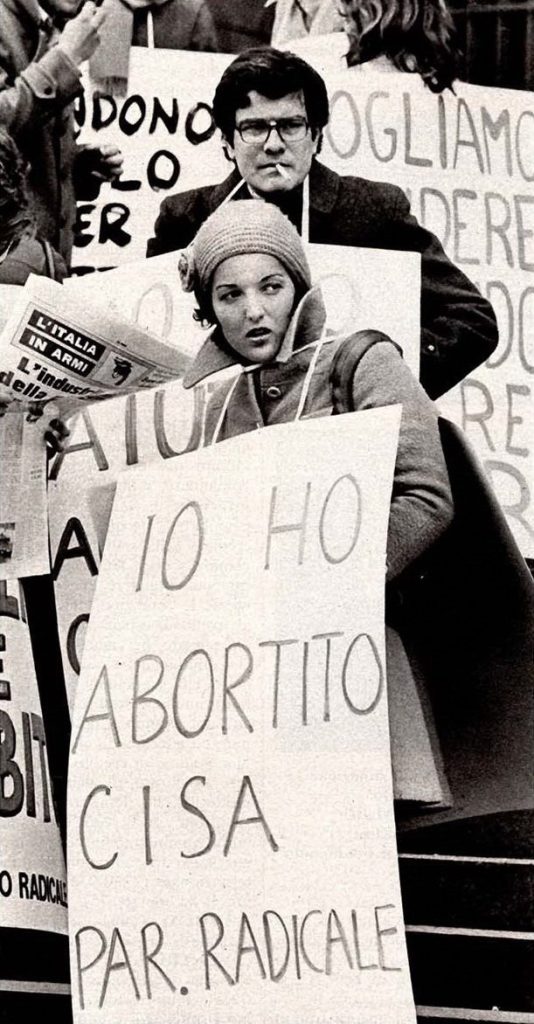

Still, the Constitutional Court and other courts in Italy played a relatively marginal role. Policy was mainly produced through the parliamentary process, beginning in 1973, when the Socialist Party MP Loris Fortuna (who advanced the law that legalized divorce in 1970) made a moderate proposal amending the penal code on abortion. And then there was the influence of the Italian Church: in 1975, the Italian bishops’ conference issued a document that reiterated traditional Catholic teaching on abortion, but also indirectly critiqued the Fascist-era concept of abortion as a crime against the integrity of race or lineage. Then came the national elections of June 1976, which in bringing about significant gains for the Communist Party (thanks in no small part to Catholic voters) also brought about the end of the anti-abortion majority in Parliament. Leftist parties (Socialist, Communist, Proletarian Democracy), liberal-capitalist parties (Republican, Liberal, and Social Democratic), and the Radical Party—supported by numerous associations and movements—soon drafted a consensus bill on abortion that passed in the lower chamber. After being initially rejected by the senate it was resubmitted, and in May 1978, it overcame opposition from Movimento Sociale Italiano (the neo-fascist party) and Democrazia Cristiana (the Christian-Democratic party, composed mostly of Catholics) to pass. The law was then promulgated by the president of the republic, Giovanni Leone, a Catholic. Neither Leone nor any of the Catholic parliamentarians who’d supported it were threatened with canonical consequences: none of them were denied access to the sacraments (in contrast to what we’ve seen in the United States not only recently but as far back as 2004).

But things didn’t end there. In May 1981, 79 percent of Italy’s registered voters went to the polls to vote on a referendum that included two questions on abortion. One, put forth by the Movement for Life (officially nondenominational but largely composed of and run by Catholics), called for the repeal of Legge 194; it was rejected by 68 percent of voters. The other was advanced by the Radical Party, which called for further liberalization of abortion law—specifically, eliminating the prohibition on abortion for women under the age of eighteen, lifting the ninety-day limit, and allowing private health facilities (not just public) to perform abortions; this proposal was rejected by 88 percent of voters. Legge 194 has remained in place since, and its defenders note that the number of abortions has plummeted in Italy over that time. Indeed, its figures on abortion today are among the lowest in the world. But other factors must be considered, such as the more widespread availability of contraceptives and the morning-after pill. There’s also the undeniable fact that Italy’s population is growing older, far fewer women are becoming pregnant, and far fewer children are being born now than in the 1970s.

Read the entire piece here.

Well, the one good thing to learn from Italy, and the rest of Europe, is that abortion laws came out of the legislative process, rather than the courts. Given the current political institutions that govern Western states, that is how it should be. That the people of such Western states consider abortion as subject to a vote, technically no different from an infrastructure bill, remains the more significant lesson. The range of qualifications and exceptions governing the regulation of abortion in Italy appears to strike some as a model of wise political prudence. Would we consider such nuance wise if equivalent qualifications and exceptions were applied to racial discrimination? Clearly some do not see a moral equivalence between the two issues. At one level, it is fair to say that most Americans support abortion under some circumstances and pro-lifers must simply accept that reality and do their best to reduce abortions. By the same token, it is fair to say that most Americans accept the basic principles of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but are not at all convinced by efforts to extend the moral authority of the Civil Rights movement beyond those pieces of legislation to Affirmative Action and the whole range of righteous anti-racism that is now absolute gospel for racial liberalism. Do we tell angry anti-racist liberals just to accept that that’s where most Americans are?

In the end, perhaps the most important lesson of Italy is its aging population and the general abandonment of family and child bearing/raising. Pope St. Paul VI continues to get much grief from liberal Catholics for Humanae Vitae, but the demographic and sociolgical data seems to bear out his dire warnings about the consequences of contraception.