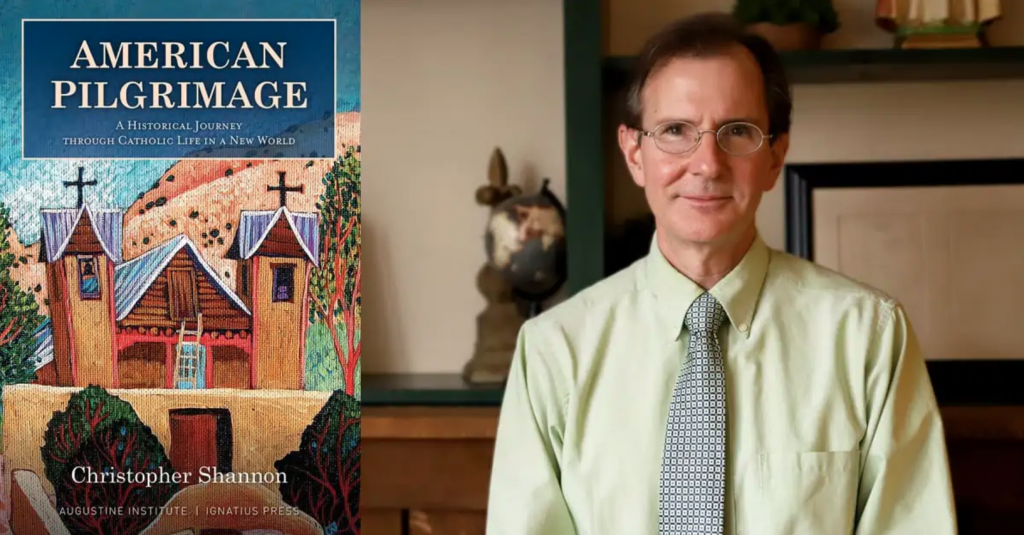

Shannon’s new book American Pilgrimage extends an invitation: Come and see

Christopher Shannon has been a presence at Current almost since its inception. He has also made his mark over the past two decades as one of the leading figures in the broad-ranging debates about what a thoroughly Christian approach to history might require. The publication of his new book will, among other things, give readers the opportunity to see how Shannon works out his thinking about history in a narrative written for a broad audience. The book arrives at a critical time for the Roman Catholic Church in the United States. If you’ll read it, you’ll understand why.

***

Your book’s title is American Pilgrimage: A Historical Journey through Catholic Life in a New World. Why?

The title directly references an earlier work I co-authored with Christopher O. Blum, The Past as Pilgrimage: Narrative, Tradition and the Renewal of Catholic History. In that work, we argued for an ideal of Catholic history that could combine the rigor of modern scholarship with explicit faith commitments and a writing style accessible to the general reader of any faith tradition, but particularly to those of our own tradition, the Catholic Church. If that work is the theory, American Pilgrimage is the practice.

I intend the word “pilgrimage” as an invitation to enter into a narrative of the past as a spiritual journey. I did not write a book about historical actors who just happened to be Catholic who came to a place that just happened to be North America and tried to build up an institution that just happened to be the Catholic Church. This is a story of Catholics struggling to be faithful to the Gospel of Jesus Christ as they build up the Body of Christ within the Church and spread the Gospel to those outside the Church.

Speaking of those outside the Church: What are some aspects of your story that you think Protestants might especially stand to gain from reading this book?

Well, I suppose readers hoping to gain something must first feel some sort of lack. I would say the book speaks to at least three areas where a certain kind of Protestant reader might be looking for spiritual and historical resources outside of their own tradition. First, I see this book as of interest to those Protestants in and out of academia who have followed the debate over Christian scholarship generated by the work of George Marsden. I participated in that debate as something of a Catholic outlier and generally argued for a more robustly faith-based approach to history, something that goes beyond having sympathy for Christian subjects and a certain insider knowledge that facilitates better historical understanding of them. Readers familiar with these issues may judge if American Pilgrimage provides a reasonable alternative to Marsden’s approach. Second, I see this book as of interest to Protestants dissatisfied with the spiritual individualism that has characterized much of Protestant Christianity in America. Protestants and Catholics experienced the same social disruptions brought on by the market revolution, but whereas Protestants responded by adapting their faith to these changes through the so-called “democratization of American Christianity,” Catholics responded by reaffirming traditional communal ties, including the submission to traditional religious authority, thus avoiding the constant denominational fragmentation that has characterized historic Protestantism in America.

Finally, this book should be of interest to Protestants open to alternative traditions of understanding the relation between faith and culture, especially as these relate to liturgy. Protestants have developed their own religious cultures, but the Reformation bequeathed a distinct suspicion of culture as a threat to faith, an ever-present source of corruption, seen most clearly in the Reformers’ assault on all the pagan residue in Catholic Christianity. The Catholic Church took these criticisms seriously but never rejected culture, even pagan culture, in the name of spiritual purity. My book shows this continued commitment to Christianizing culture from the early work of the evangelization of Native peoples to the reforms of the liturgical movement, which sought to renew Catholic culture through a fuller, more conscious engagement with the liturgy.

Did your thinking about the Church change in the course of writing the book?

The book is the fruit of thinking, writing, and teaching about the history of the Church in America, going back twenty years to my time at the Cushwa Center at Notre Dame. Given this, I can’t say the actual writing of the book changed how I think about the Church. The biggest challenge in trying to write a “warts and all” history of the Church in our present time is to see beyond the “warts” to the “all” without appearing to give the Church a pass on matters in which it has shown itself less than divine: human, all too human. I decided to respond to the challenge not by concocting some perfect balance of “merits” and “demerits” but rather by adopting a framework that takes both the divine and sinful nature of the Church as a given: Augustine’s notion of the struggle between the City of God and the City of Man. This theological framework required a distinct narrative framework, thematic rather than strictly chronological; for this, I turned to organic metaphors (“Roots,” “Fruits,” “Seasons”) appropriate to presenting the Church as the Body of Christ, rather than simply a religious institution that goes through ups and downs.

Above all, I have tried to provide an alternative to the “rise and fall” narrative that structures so much American Catholic history, both conservative and liberal. Worldly institutions rise and fall. The Church, at its best, flourishes; at its worst, it endures. Much of the “fall” part of the narrative refers to the Church in the period since World War II. In writing the history of that period I came away impressed by the clarity and wisdom of the Church’s response to modernity expressed in the documents of Vatican II and the best of the social and spiritual movements that inspired or were inspired by the Council. I also came away saddened by the historical fact that the message of the Council fell on deaf ears, even within the Church itself. As a small core of liberal and conservative activists fought over the “spirit of Vatican II,” most American Catholics simply found something else to do with their Sundays, and their lives.

What misconceptions about Catholic history in America does your book address?

Would that people knew enough about American Catholic history to have misconceptions! I wrote the book in part because of the vast ignorance—outside of the world of those who study the subject professionally—of the basic facts of the story of the Church in America. Still, yes, I suppose I wrote the book as a corrective to what I take to be misunderstandings about the American Catholic past. To the scholars, I offer a narrative that takes the faith itself as normative and puts ethnic cultures at the heart of the story. Mainstream scholarly treatments have tended to judge the Church by the degree to which it lives up to the standards of American democracy. I have no problem with the Church’s embrace of democracy, but support for democracy stands at best a distant third to its primary duties to spread the Gospel and build up the Body of Christ. Catholics who are not academics have absorbed a less reflective version of this emphasis on democracy simply by a genetic, instinctive patriotism that makes it very difficult for them to consider that there might be some tension between their Church and their Country. By de-centering the political story, I hope to disrupt the conventional story of the slow, steady progress of the Church in America to consider what has been lost, particularly in terms of culture and, for lack of a better word, “peoplehood.”

As for non-Catholics, I am not sure what conceptions or misconceptions they may have. Post-World War II political alliances between Catholics and Protestants, both liberal and conservative, have done much to mute the old Protestant anti-Catholicism, but I imagine that the hierarchical structure of the Church might still render it suspect in the eyes of more egalitarian Christian traditions. Catholic life embraces hierarchy but is not reducible to it. Among my many reasons for writing the book, I suppose one was simply to make the Church attractive to non-Catholics. The book is my way of saying, “Come and see.”

Why does Our Lady of Guadalupe play such a central role in your narrative?

Guadalupe embodies a central theme of the book: the incarnation of a universal faith in particular cultures, in new ways in a New World. The image on the miraculous tilma associated with the 1534 apparition shows a woman, identified as the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, yet dressed in native Aztec garb; moreover, the Virgin Mary granted this miraculous image to Juan Diego, a simple Native peasant and recent convert, the lowest of the low in the social hierarchy of New Spain. Aside from the particular tradition of inculturation that Guadalupe bequeathed to Mexican Catholicism, she symbolizes a blending of the Old World and the New that would find expression in the ethnic diversity of the immigrant Church in the United States from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. For much of this period, Catholics would be among the lowest of the low in a society dominated by Anglo-Protestants. The postwar period saw Catholics achieve material success at the cost of abandoning earlier cultural syntheses and, in many cases, the faith itself. The story of Guadalupe and Juan Diego challenges deracinated, assimilated American Catholics to consider the virtues of cultural distinctiveness and spiritual (and yes, material) poverty.

Eric Miller is Professor of History and the Humanities at Geneva College, where he directs the honors program. His books include Hope in a Scattering Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch, and Brazilian Evangelicalism in the Twenty-First Century: An Inside and Outside Look (co-edited with Ronald J. Morgan). He is the Editor of Current.

I am grateful for the observation that the Church at its best flourishes, and at its worst endures.

Thanks. Yes, sometimes just a slight change in words makes a difference.

Great interview. I’m looking forward to reading the book!