Over three decades after his resignation ended the USSR, how much has changed?

In what can be considered an exemplar of news dissemination in these days of social media, I first learned of the death of Mikhail Gorbachev on Twitter when Ukrainian journalist Illia Ponomarenko quipped casually, “Gorby is dead,” linking a Russian-language news release from Moscow. And in a quintessential reminder of the adage, immortalized in the popular Russian film Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, Russian media has been critical right away in discussing his legacy.

For me, Gorbachev’s legacy is personal, even as it illustrates some of the criticism that the current Russian thought leaders bear against it. Blamed rightly for the dissolution of USSR, his policies are directly responsible for two outcomes that felt equally significant in my life when they happened, but one of them turned out to be of much greater importance. First, Gorbachev’s monumental opening of the borders allowed a historic 400,000 Russian Jews to leave the country in 1990-1991. My family contributed four of these 400,000. And second, my stuffed yellow bear, the companion of my childhood without whom I could never imagine going to sleep, was not allowed to come along. Over three decades later, I guess I am still just a little bit sad about it.

People who have never lived in a country with closed borders may never understand what it is like to be forbidden to move freely. But that is a world in which Soviet citizens had effectively lived since the days of Lenin. It’s not just that the citizens of USSR could not travel abroad except with special permission. Internal travel too required permission, as did moving from one place to another. For instance, the process of transferring jobs did not entail merely interviewing for a job in another city. Security checks had to verify that you were not a dissenter, an enemy, a risk that should be prevented from moving to, say, a major city, for that city’s sake.

After all, even one dissenter, one enemy, one drop of the wrong leavening, could corrupt the whole state, as so many warning tales regaled. Traitors lurked everywhere, propaganda posters from the earliest days of Soviet rule reminded. For Jews, it seems the policies were even harsher. They especially suffered from policies controlling their movements and where they could settle, both under the Tzars and under Soviet government. And antisemitism was rampant enough that a few years after marrying my father, my mother changed her very distinctly Jewish last name (Katz) to my father’s very Russian one (Popov). Her job prospects improved overnight.

I did not recognize this situation as a child in a country whose news was tightly controlled, but my family’s experience like that of other Russian Jews was part and parcel of the complex world of Cold War politics. As Shaul Kelner recently explained in his analysis of Russian emigration policies vis-à-vis the Jews, “Cold War politics made the predicament worse. The Soviet government’s domestic persecutions of Jews were bound up in its foreign policy toward Israel. When the country declared independence in 1948, the U.S. and USSR each raced to secure its allegiance. After Israel aligned with the West, however, the Soviet Union became patron of the Arab states and broke diplomatic ties with Israel in 1967.”

This was the history Gorbachev’s friendlier emigration policies served to undo for a time. Taking advantage of an opportunity they feared might be all too brief, my parents began the arduous process of applying for permission to emigrate from Russia to Israel in 1990. And part of that application process involved securing parental permission. Who came up with this idea of requiring adults—men and women in their third, fourth, fifth, or greater decade of life—to get permission from their parents to leave the Soviet Union? And how many people at the end were unable to leave either because their parents denied them permission or because they could not locate parents from whom they were estranged? In any case, that was the requirement, and so it was that my parents at the tender age of 39 had to ask their parents for written permission to emigrate.

While my mother’s sole living parent, her mother, granted permission right away, my father’s parents had concerns. For several weeks, on a number of evenings after coming home for dinner after work, my father would catch the underground train to the other end of Leningrad and talk with his parents, trying to persuade them to grant permission. They agonized over the decision intensely, it seems, worried that we were making a huge mistake. What if you, a successful nuclear physicist, would never get a job in your field again, my grandfather fretted to my father. And what about the children? Would they succeed in a different country in which none of you know the language?

At the end my grandparents granted permission, and in March 1991 my family of four was on a train heading out from Russia to Hungary. At the border our Russian passports were taken away, as was the custom at the time. So it transpired that for about two weeks, between the moment we left Russia and until we landed in Tel Aviv, we were citizens of no country.

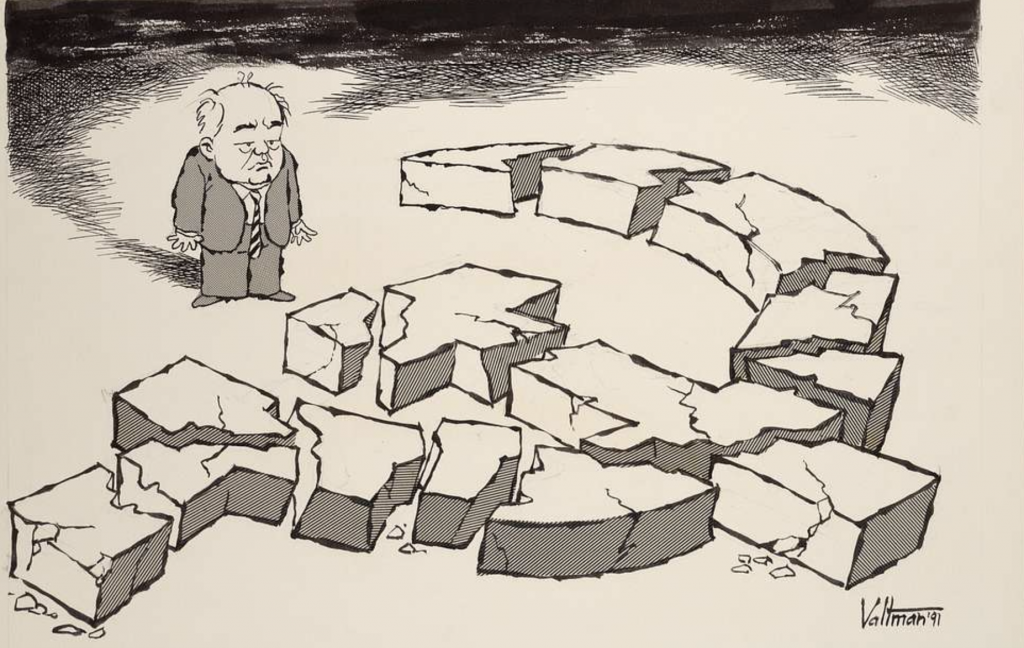

Just over three decades later, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has uncovered a truth so many could not have imagined: Maybe the Cold War never ended after all. The same Gulags, terror tactics, state control of the media, and restrictions against emigration of Jews are all in effect again. Another KGB man is in charge of the country. What does this mean for Gorbachev’s legacy, which seemed so conflicted ever since his shocking resignation from power ended the USSR’s seventy-four-year existence?

But perhaps this is not the question to ask. Instead, the ruminations of a much earlier writer come to mind: Augustine, bishop of Hippo, who warned in the early fifth century CE against idealizing leaders of empires and attributing to them any extraordinary achievements. These empires will all rise and fall, and the corruption of their leaders will be laid bare for all to see one day, sooner or later. The fate of the city of Rome and the empire it once led is just one example of this phenomenon at work. Only one city is eternal, and it isn’t here. And so, Augustine might say, maybe it’s okay that Moscow, yet another great earthly city, still doesn’t believe in tears.

Nadya Williams is Professor of Ancient History at the University of West Georgia. She is a Contributing Editor for Current.