Sometimes the heroes of our childhood become the heroes of our adulthood

Forty-five years ago this month, August 12, 1977 to be exact, Ed Ott body-slammed Felix “The Cat” Millan in Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium. It was the last time Millan would ever set foot on a Major League Baseball field. Pittsburgh Pirates manager Chuck Tanner said the New York Mets second baseman “got what was coming to him.”

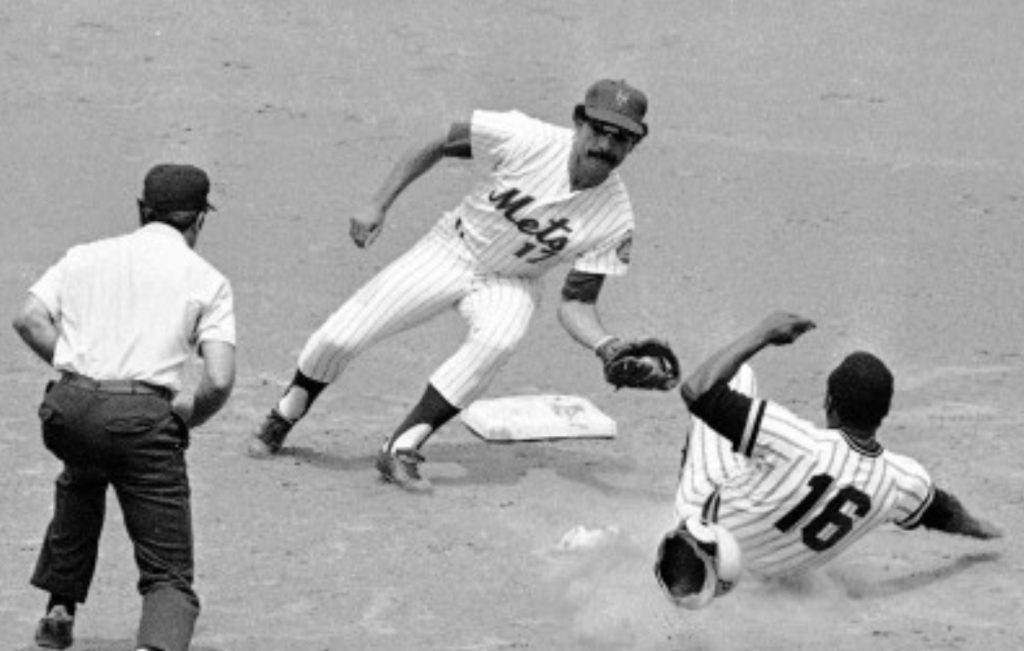

It was the sixth inning of the second game of a doubleheader when Ott, the Pittsburgh catcher with a reputation for physical play, slid hard into second base to prevent the veteran infielder Millan from turning a double play. The Pirates were in the thick of the National League East playoff race, sitting a few games behind the first-place Philadelphia Phillies. It was an important game.

As for the Mets, the glory of the 1973 World Series season was long gone. Two months earlier the team had traded its ace pitcher Tom Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds. Jerry Koosman and Jon Matlack, the other star hurlers from that World Series team, were struggling through losing seasons. The Mets were in last place, more than twenty games behind the Phillies. Morale was low. Frustration was high.

Millan, the former gold-glover and a key member of that 1973 team, rose to his feet after the play and, with the baseball hidden in his clenched fist, punched Ott in the cheekbone. After staggering from the blow to his face the former high school wrestler, who had about thirty pounds on Millan, picked him up and threw him to the ground. The World Wrestling Federation’s Superstar Billy Graham couldn’t have done it any better. Only unlike professional wrestling, this was real. Millan was taken off the field on a stretcher with a broken clavicle and dislocated shoulder. Ott was ejected from the game. Tanner wanted Millan to be suspended for the rest of the season.

I listened to this game on a transistor radio in the northern New Jersey home where I grew up. When I heard what happened to Millan I punched my bedroom wall in anger. It was a natural response for an eleven-year-old boy when one of his favorite players was on the losing end of an on-field scuffle. Like all fans, I suffered with the Mets during that season. I understood, at least in part, Millan’s frustration. To this day I can’t hear the name “Ed Ott” without my blood pressure rising.

Baseball and the Mets were my world in those 1970s summers. I spent hours walking around my yard enacting imaginary games. I would work my way through the Mets lineup—Mays, Unser, Jones, Milan, Kranepool, Staub, Garrett, Milner, Grote, and Harrelson—imitating the batting stances of each player and doing play-by-play in my head. And when the Mets finally exhausted their three outs in my backyard fantasy inning, I would put on my mitt and perform the pitching windups of Tom Terrific, Koosman, Matlack, and Tug McGraw. Seaver had his share of no-hitters and, if one of the starters struggled, McGraw always got the save. On at least one occasion a neighbor asked my parents if I was OK.

Millan had the most unique batting stance in baseball. He was what they called a “slap” hitter. He held his hands nearly a foot from the bat knob. To this day no player has choked up to such a degree. Of his 1,614 career hits, 1,328 were singles. In one game in 1974 Milan went four-for-four with four singles, only to have the player hitting behind him in the Met’s lineup—Joe Torre—hit into a double play every time. (Torre credited Millan with paving the way for him to break the major league record for hitting into the most double plays in one game. “I couldn’t have set a record without Millan!,” he said.) “The Cat” was a .278 lifetime hitter and is remembered for his amazing eye for balls and strikes and his incredible bat control. He continues to have the best bat-to-strikeout ratio of any major leaguer who started their career after 1950.

What surprised me the most about Millan’s violent reaction to Ott’s hard slide into second base, and what continues to surprise me about it, was just how out of character it was for the young Puerto Rican. I remember him as a quiet, almost shy, workmanlike infielder who was not prone to fits of anger. He came to Shea Stadium every day and did his job. No drama. He was the first New York Met to play all 162 games in a season, a sign of his physical conditioning and his love of the game he learned as a boy growing up in poverty. From all reports he was a good teammate. During Millan’s rookie season with the Atlanta Braves Hank Aaron picked him as his roommate when he learned that Millan, like him, did not drink, smoke, or party. Like one his mentors, Roberto Clemente, Millan played the game with class.

What happened on August 12, 1977 in Pittsburgh was a sad ending to a great career. It also reminds us that we are all human beings who sometimes let the heat of the game, and the frustration of a bad season—whatever that game or season may be—get the best of us.

As I conducted research for this piece, I learned something about “The Cat” I didn’t know back when I was hunched over in my backyard choking-up on my bat and trying to imitate the voice of Met’s announcer Bob Murphy: Millan is a man of deep religious conviction. After he retired from Major League Baseball he played a few seasons in Japan. He converted to Seventh Day Adventism and managed to work out a deal with the Yokohama Taiyo Whales that allowed him to sit out games on Saturday, the Seventh Day Adventist sabbath. When his contract with the Whales ended Millan returned to Puerto Rico, was baptized in his newfound faith, and regularly taught a Bible class for eight-to-ten year olds.

Since his retirement from baseball Millan has been active as a spokesman for baseball in Puerto Rico and New York City (he serves as the honorary commissioner of the Felix Millan Little League) and he and wife Mercy have also used their platform to serve his church. They have been married for more than fifty years. In a 2014 interview he said the greatest moments of his baseball career—yes, his baseball career—were the days his son and daughter were born. Humility and gratitude all the way.

Millan says he has forgiven Ott. The two men apparently reconciled at some point in the years following the incident.

Sometimes our childhood heroes disappoint us. As we grow older and learn more about the people we admired in our youth, we find things out about their personal lives that we wish we had never uncovered. We prefer the nostalgic longings of the backyard imaginary baseball games and the choked-up swing of the bat over the messiness of lives shaped by a broken world. But I am happy to report that Felix Millan, the thirty-something infielder I admired as a kid, is still a guy I can root for this week as he celebrates his seventy-ninth birthday.

Happy Birthday, Felix!

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current.

Thanks, John Fea, for a splendidly crafted memory of an example of the magic of baseball!

Rick Wilson

Thanks, Rick. I hope you are doing well.