“Rumor, swiftest of all evils; she thrives on speed and gains strength as she goes.”

In Book Marks, an occasional feature at Current, we take fresh cuttings from old books (or about old books). They may often be about books, writing, education, communication, and the life of the mind generally, though we reserve the right to snap a sprig of greenery that simply tickles the fancy.

Why look at old books? Because there’s a slat loose in the fence they’ve got us penned up in, and we can jiggle it free to see better what’s going on out there.

With each extended quotation we offer an orienting comment, but that’s not where the action is. The question is whether the words of those long dead may speak to you.

*

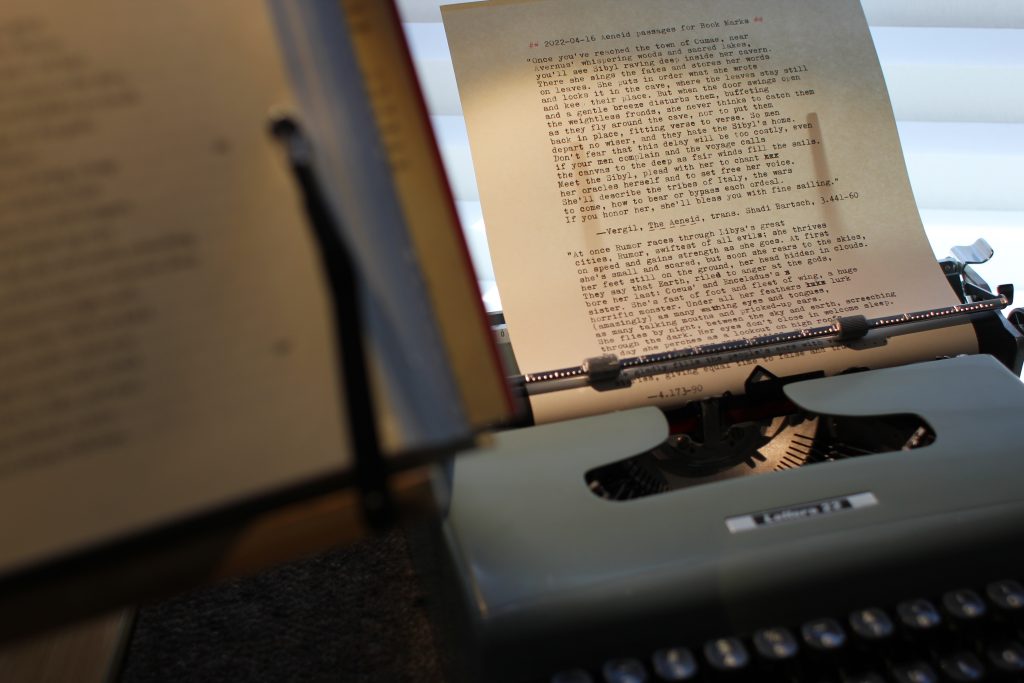

Virgil (or Vergil, take your pick, I guess) lived a long time ago, but he seems to have known quite a lot about the fragility of written communication—or rather, about our ability to write things down but still not attend to them. We often depart no wiser. Shadi Bartsch brings a sinewy energy to her new translation of this epic of trash talk and colonial violence.

Hear what they have to say:

Once you’ve reached the town of Cumae, near

Avernus’ whispering woods and sacred lakes,

you’ll see Sibyl raving deep inside her cavern.

There she sings the fates and stores her words

on leaves. She puts in order what she wrote

and locks it in the cave, where the leaves stay still

and keep their place. But when the door swings open

and a gentle breeze disturbs them, buffeting

the weightless fronds, she never thinks to catch them

as they fly around the cave, nor to put them

back in place, fitting verse to verse. So men

depart no wiser, and they hate the Sibyl’s home.

Don’t fear that this delay will be too costly, even

if your men complain and the voyage calls

the canvas to the deep as fair winds fill the sails.

Meet the Sibyl, plead with her to chant

her oracles herself and to set free her voice.

She’ll describe the tribes of Italy, the wars

to come, how to bear or bypass each ordeal.

If you honor her, she’ll bless you with fine sailing.

And in a second passage we get a first-century BC insight into why communication is not always a good thing. It depends on what you’re communicating.

At once Rumor races through Libya’s great

cities, Rumor, swiftest of all evils; she thrives

on speed and gains strength as she goes. At first

she’s small and scared, but soon she rears to the skies,

her feet still on the ground, her head hidden in clouds.

They say that Earth, riled to anger at the gods,

bore her last: Coeus’ and Enceladus’s ,

sister. She’s fast of foot and fleet of wing, a huge

horrific monster. Under all her feathers lurk

(amazingly) as many watching eyes and tongues,

as many talking mouths and pricked-up ears.

She flies by night, between the sky and earth, screeching

through the dark. Her eyes don’t close in welcome sleep.

By day she perches as a lookout on high roofs

or towers and alarms great cities. She’s as fond

of fiction and perversity as truth. And now

she gladly fills the people’s ears with varied

stories, giving equal time to false and true. . . .

—Vergil, The Aeneid, trans. Shadi Bartsch (Random House, 2021), 3.441–60 and 4.173–90

*

Jon Boyd is keeper of Book Marks at Current. He is associate publisher and academic editorial director at InterVarsity Press, the saxophonist in an improvisational rock band, a user of mechanical typewriters and postage stamps, and (with his wife and daughters) a resident of the City of Chicago.