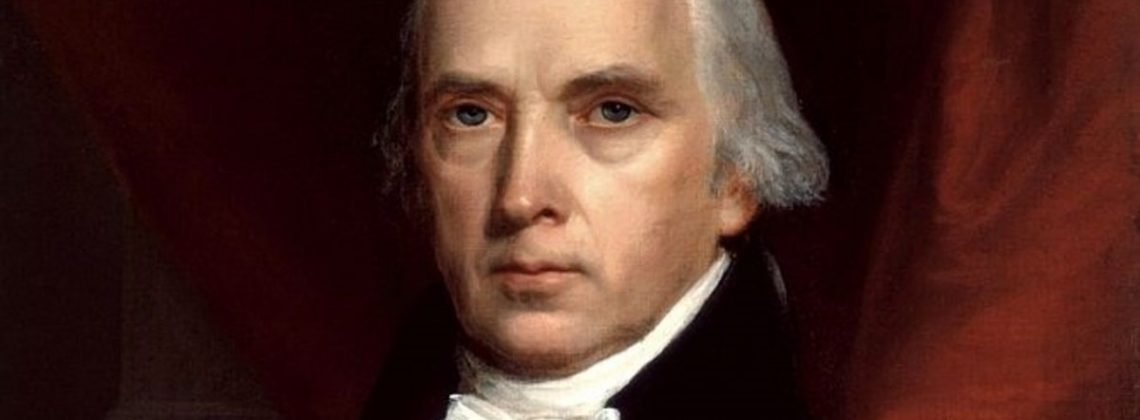

The United States Constitution, James Madison argued, only works when people are spread-out geographically. Social media shrinks that distance. Here is a taste of political scientist Danielle Allen’s piece at The Washington Post.

When we teach constitutional history, we often teach the 10th essay — “Fed 10,” as it is known — to explain how the Constitution was designed to solve for faction. Madison argued that building a representative instead of a direct democracy would mitigate the problem.

Robust disagreement would always be part of any constitutional democracy, Madison argued. It is freedom’s necessary price. Tamping it out is not only impossible but undesirable. But reasonably public minded representatives would synthesize opinion from around the country. Coming together in Congress, they would refine public opinion and deliver a moderated, filtered version to steer the nation.

The notion that our representatives would serve as national shock absorbers sounds quaint. But even more important, it was only half of Madison’s argument. We neglect to teach the other half.

Madison also expected that the breadth of the new nation and geographic dispersal of its residents would themselves dampen the consequences of those robust disagreements.

“Extend the sphere [of the country] … and it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. … The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States.”

Madison anticipated that the breadth of a broad republic — our very rivers and mountains — would protect against the formation of dangerous factions because it would be hard for people with extreme views to find each other and coordinate. Because of geographic dispersal, people would have to go through representatives to get their views into the public sphere. This would mitigate the impact of faction.

In short, geographic dispersal was an actual premise of the Constitution’s original design. It was a pillar undergirding the very viability of our system of representation.

No more. Madison couldn’t anticipate Facebook, and Facebook — with its historically unprecedented power to bind factions over great distances — knocked this pillar out from under us. In this sense, Facebook and the equally powerful social media platforms that followed it broke our democracy. They didn’t mean to. It’s like when your kid plays with a beach ball in the house and breaks your favorite lamp. But break it they did.

Now, the rest of us have to fix it.

Read the entire piece here. I am going to use this when I teach Federalist #10.