Thirty years after Mark Heard’s death he’s still showing us what we’ve missed

Long Form features spill out a little more slowly, making possible a deeper encounter with the essay’s central themes—and with the author, too. Pour a cup of coffee, settle in, and enjoy. It will be worth your while.

***

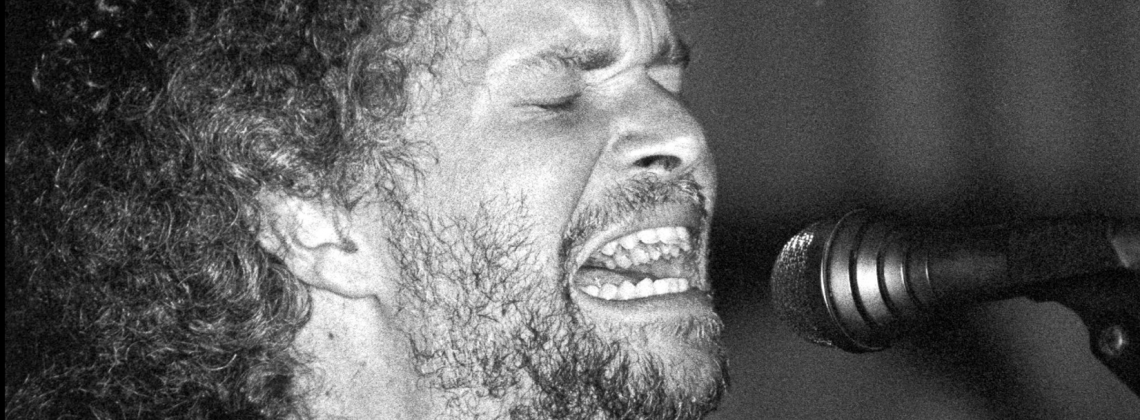

“Oh, the mouths of the best poets speak but a few words / Then lay down, stone-cold, in forgotten fields.”

That’s Mark Heard in “I Just Wanna Get Warm,” from his 1991 album Second Hand. Like a lot of what Heard wrote, these words came to seem prophetic after his untimely death just a year later in August of 1992, aged forty. We’re talking about a songwriter whose first song on his first album was called “On Turning to Dust”; the last song on his last album, released just weeks before his heart gave out onstage, is “Treasure of the Broken Land,” one of the greatest songs ever written about grief and resurrection. It’s hard to think of another songwriter so consistently interested in his own mortality. Dylan comes close on Time Out of Mind, but Heard lived in that place for almost two decades. The recent reissue of his 1990 album Dry Bones Dance reveals that for most of his life he was aware of the heart defect that ended up killing him, which might explain both his fixation on death and his tremendous work ethic.

Heard emerged from the Jesus Movement of the 1970s and came out of conservative evangelicalism, having lived at L’Abri, Francis Schaeffer’s intellectual commune in Switzerland. At the time that Heard lived there, Schaeffer had not yet become involved in the American political right. Instead, L’Abri seems to have offered him a broader and more artistically and intellectually rich alternative to American Christianity. Even so, Heard would chafe against his connection to evangelicalism for the rest of his career to one degree or another, without ever exactly renouncing it. This dynamic was artistically productive for Heard, as it was for a number of other philosophically minded Christian singer/songwriters in the 1980s and ‘90s. It’s hard to listen to Heard’s later music without feeling that he had been unfairly ghettoized in the “Contemporary Christian Music” (CCM) industry. And yet Heard’s frame of reference remained Christian, even though his concerns were always substantially broader than those of, say, Michael W. Smith.

This is true even of his rather CCM-ish early albums, 1975’s self-titled debut and 1979’s Appalachian Melody. These are, for the most part, folk-pop in the James Taylor/John Denver vein, mostly covering standard Jesus Movement topics. “Two Trusting Jesus” is a fine example—corny but earnest, like a lot of adult contemporary music of the era. And every so often in these early albums you stumble across something that points outside the CCM milieu: “On Turning to Dust” is probably the best song of Heard’s first decade, but the self-titled album also features an unexpected cover of William Cowper’s odd eighteenth-century hymn “There Is a Fountain Filled with Blood,” and, odder still, Moog renditions of “Greensleeves” and Bach’s “Passion Chorale.” The title track to Appalachian Melody is another early masterpiece, a blast of poetry not terribly common even in the artsier corners of the Christian rock world in 1979:

Appalachian melody

Drifting softly down

Instruments of gold and red and brown

Do not need no dulcimer

Or banjo-fiddle sound

For right now, I’ll watch these leaves come down

For the most part, the problem with Heard’s early work is not the songwriting; even at its most CCM-ish there’s always insight there, especially if you have any affection at all for the hyper-earnest Jesus Movement. No, the problem is his voice, which takes the milquetoast qualities I find so aggravating in James Taylor and centers them. This is mildly annoying on a folk-pop number like “Castaway,” but when Heard tries to do actual rock music in the 1970s the results are infuriating. Exhibit A: “On the Radio,” the opening track of Appalachian Melody, in which Heard mugs for the microphone like he’s doing a voice for a local-TV puppet show. I know lots of Heard fans love this song; I find it almost unlistenable.

Now is the time to say that I did not come across Heard’s music until after his death, through a greatest-hits release called High Noon, which covered only material from the last three years of his life, the trilogy of Dry Bones Dance (1990), Second Hand (1991), and Satellite Sky (1992). I don’t think late-period Mark Heard is one of the all-time great rock vocalists; his strengths were always in his writing and his arrangements. But his voice always suits these later songs—there’s a desperate and depleted quality to it that makes it quite effective. When I finally dug up his early albums a few years ago I was shocked at the difference. What the hell happened? The answer, I think, is cigarettes. In the liner notes to the Dry Bones Dance reissue, Buddy Miller describes Heard’s home studio as having “a soda can of cigarettes on the outside windowsill.” I don’t know how long he smoked, or at what rate, and I won’t say that smoking was the most prudent habit for someone who knew he had a heart condition—but artistically it was the right choice.

Heard, for the most part, moved away from folk-pop and soft rock in the 1980s; as tastes changed, so did his music, although I don’t want to make it sound as if he was chasing trends. While most of these albums are also of mixed quality, they’re never without standout tracks. 1981’s Stop the Dominoes embraces a low-fidelity version of the corporate rock sound popular at the time. This technique allows Heard for the first time to record some convincing rock songs: I’m fond of “Stranded at the Station,” a semi-silly narrative about missing a flight, and of “One Night Stand,” a musician’s diary that shows Heard caroming from city to city, train to bus, cheap motel to stage. There’s an even better musician song two years later on Eye of the Storm: “In the Gaze of the Spotlight’s Eye.” This one features no joke, just the kind of lonely self-interrogation that any kind of artistic vocation demands. The title track of Victims of the Age combines that arena-rock production with the chiming guitars of The Byrds or Big Star, while the lyric curses the Babel of public voices in the modern world. “Schizophrenia,” from 1985’s Mosaics, is probably Heard’s best rock song of the ‘80s, anchored by a neat little George Harrison riff, a melodic baseline, and the standard pop-cultural conflation of schizophrenia and dissociative-identity disorder.

The two albums where you can really feel Heard carving his artistic vision out of the rock, however, are 1984’s Ashes and Light (recorded after Mosaics but released before it) and 1987’s Tribal Opera, credited to iDEoLA rather than to Heard himself. Ashes and Light varies Heard’s arrangement and production techniques substantially, mixing hard rock, folk, and country instrumentation. Take “True Confessions,” a rootsy groove without a chorus whose fiddle is subtly backed by a rumbling synthesizer, or “In Spite of Himself,” a folk-pop number alternating among accordion, synthesizer, and harmonica. His lyrics are better than ever; whereas even Victims of the Age occasionally featured a culture warrior’s disgust with the world, here Heard struggles to understand the motivations for the war itself, and to find some hope. “I’m not a man you might call optimistic,” he sings on “Washed to the Sea.” “Sometimes it pains me to see what I see / But truth is a river that is sober and slow. / And tears will be washed to the sea.”

Tribal Opera is a real oddity, a one-man-band record built on electronics and samples and drawing, I believe, on the work of Marshall McLuhan. I’m not sure anyone following Heard’s career in the ‘80s could have predicted iDEoLA—sonically speaking, it’s as strikingly artificial an album as I’ve ever heard, but its lyrics are incisive, even brutal at times. “I wish I’d never been told / That the species has souls,” Heard growls on the opening track, “I Am an Emotional Man.” Heard plays with the synthesized quality of the sound to critique and parody the artificiality of Reagan-era society. In this sense, Tribal Opera feels dated, but its concerns remain relevant as our own society has become mechanized in ways that would have been difficult to predict in 1987.

The album’s centerpiece is “How to Grow Up Big and Strong,” later covered by Rich Mullins and, I kid you not, Olivia Newton-John. Its narrator is some sort of barbarian who has been transplanted into the modern world, discovering that he recognizes much more of it than one might expect him to: It’s all a power-grab, and the strong man continues to dominate, even if he has exchanged his club for an atom bomb. How can a person with actual thoughts, actual feelings (“obsolete tears”) live in a world like this? Tribal Opera doesn’t offer much of an answer, unless its mere existence, its offer to share our horror, is an answer, and a hope.

But Heard’s reputation is built primarily on his last three albums. That’s where his poetic promise flowered and he finally shook loose of the Christian music industry that had never wanted much to do with him anyway. The lyrics on these last three albums are superb. Here’s a brief sampler:

We will roll like an old Chevrolet

The road to ruin is something to see

Hang on to the wheel, for the highway to hell

Needs chauffeurs for the powers that be

(“Rise from the Ruins”)

I’m old enough to know

That dreams are quickly spent

Like a pouring rain on warm cement

Or fingerprints in dust

Nectar on the wind

Save them for tomorrow, and tomorrow lets you down again

(“House of Broken Dreams”)

It’s the quickstep march of history

The vanity of nations

It’s the way there’ll be no muffled drums

To mark the passage of my generation

(“Worry Too Much”)

You see me like a prism sees a candle

I’m scattered into differing hues

(“Love Is Not the Only Thing”)

Pray for the foothills

Home to the drones of power lines and rock doves

Mountains gray as velvet

Field for dots of yucca, white with jacarandas

Facing the sky as the day burns away is a desert in mourning

Sheltering the dead stones

Cradle of the lost bones

Home of eternal comings and goings

(“Another Day in Limbo”)

Light in the dark eyes, coal into diamonds

Shelter from heavy skies, sand into pearls

Bread for the breathless, cloth for the fresh wounds

Order and chaos orbit the half-world

The taste of a color, flavor of light

None but a blind man can measure the weight

I am deaf-mute, idle as statue

Music of hemispheres lost in the half-haze

(“Hammers and Nails”)

I could go on. Heard’s lyrics on these albums are as close to poetry as pop music ever gets; certainly we’re a long way from “Two Trusting Jesus,” whatever the charms of the earlier song.

The lines I have quoted should demonstrate a favored technique of Heard’s, the ecstatic list of descriptions, physical or spiritual, that adds up to more than the sum of its parts, a sort of minor aesthetic miracle. (He makes full use of his newly urgent voice here; a song like “Tip of My Tongue,” from Satellite Sky, doesn’t have a melody so much as a perfectly phrased series of yelps.) It’s as if Heard, feeling the end approaching, is trying to name everything he sees and feels, to get it on paper and magnetic tape while he still can. Like all great artists, he shows us what we have somehow missed in our worlds and in our souls.

Songs are more than lyrics, of course, and the music of these last albums is worth noticing, too. I like to think of Heard as becoming obsessed with certain semi-obscure folk instruments: the accordion and hammered dulcimer on Dry Bones Dance, several of whose songs are heavily influenced by zydeco, and then the mandolin on Second Hand and Satellite Sky. That final album in particular uses the mandolin—an instrument, let’s admit, with a relatively limited sonic range—in ways that Bill Monroe or even Peter Buck wouldn’t have dreamed. Somehow Heard got his hands on an electric mandolin, which he used to create a kind of post-punk folk record whose sound owes as much to The Unforgettable Fire as to John Wesley Harding.

Second Hand, the middle entry in the trilogy, is a more straightforward folk-rock record than the other two—which is not an insult; in fact, it features what on most days I would call Heard’s best song. The rock canon doesn’t have a lot of convincing adult love songs, which I think is because ninety-nine percent of rock musicians, including the geniuses, are permanently stuck in adolescence. But “Nod Over Coffee,” in its modest claims of fidelity in a disappointing and banal world, gets at the beating heart of marriage.

“If I weren’t so alone and afraid,” Heard sighs to his wife at the breakfast table, “they might pay me what I’m worth.” But he sees that, however much success he might attain, his wife deserves better, that she is in some sense settling for him, as we all settle for one another, and that the most beautiful part of marriage comes unexpectedly in that mundanity and disappointment. Then they finish their coffee, say goodbye, and head out into the world that doesn’t give a damn for either of them. What’s better, or sadder, or truer, than that?

When an artist dies in his prime, the temptation is to mourn the art he never had a chance to make. And that’s doubly true for Heard, who’d really come into his own as a singer and songwriter only a few years before he died. But we should be thankful for the music he left behind: His artistic achievement is so wide and deep that no plunge into it will exhaust it. Heard’s work will stand the test of time, I am sure, even if only a few thousand people ever hear it. It’s a small kind of immortality that the writer of “Nod Over Coffee” would surely have understood and appreciated.

Michial Farmer is the author of Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction (Camden House, 2017) and the translator of Gabriel Marcel’s Thirst (Cluny, 2021). He teaches history in Atlanta.