We are the boy. We are the problem.

Trees bear a lot of weight for humans.

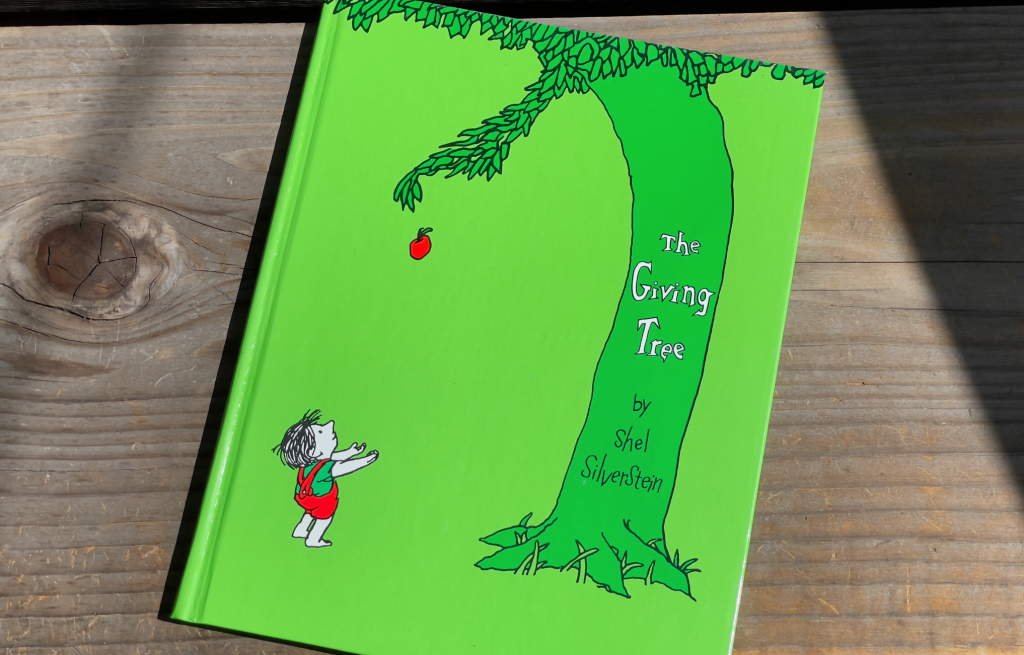

The US Postal Service made that clear this spring with its release of a stamp honoring Shel Silverstein. Other images could have commemorated the author/illustrator, bearded and rakish-looking on dust jackets, but the USPS clipped from the cover of The Giving Tree (1964): a boy in overalls with arms outstretched to catch an apple from the bowed-down bough of a tree.

The picture might look wholesome, even cute, to people remote from childhood or parenthood. Not so much if you actually remember The Giving Tree.

The picture comes from the honeymoon phase of a long relationship between boy and tree. When the boy is young each delights in the being of the other. When the boy gets older, he mostly wants stuff from her. (I’m not making that up. The tree is a she.) As a small child he gathers her leaves and eats her apples and hugs her. When he outgrows these pursuits he keeps visiting, bringing inarticulate needs, which the tree fills by giving away parts of herself. The refrain “and the tree was happy” follows each self-gift. As weedy adolescent, the boy comes to say, “I want some money. Can you give me some money?” The tree tells him to take her apples to sell. As grown man with receding hairline he wants a house, so she tells him to cut off her branches to build one. Wearied by life, he wants to escape, so the tree gives her trunk for boatbuilding. Having sailed away and come back, the stooped old man returns and wants more. But a stump is all that is left: He had already taken everything else the tree had to give. The tree offers the stump as a seat. He sits. And the tree was happy. The end.

Veteran contributor to Playboy and among the authors writing new kinds of books for the young—no more boring well-behaved children behaving politely—Silverstein did not want to dictate interpretation for what the jacket copy describes as a “moving parable for readers of all ages.” Some readers have found the book a parable of generosity, others of dysfunctional relationships. Read to me as a child, the story seemed a version of the fisherman’s wife’s tale, warning against asking for too much. Read to my own children, it was hard to see as anything other than a grotesque caricature of motherhood. The boy would “climb up her trunk”? He liked to “sleep in her shade”? What else could this be? Not only does the tree/mother keep giving to one whose wants are never satisfied, but she has to be clever about it, to solve with limited resources the limitless desires the boy cannot manage on his own. The boy hardly knows what he wants with money, but he allows her to turn herself into a commodity and conceal the transformation from him. In the end, he hardly recognizes that it was he who reduced the tree to stump, a depletion he caused and resents.

It is possible that Silverstein meant the tale as a critique of such parental relationships, though I doubt it, given the book’s usual audience and its capacities. And the jacket blurb does deem the book an “affecting interpretation of the gift of giving and a serene acceptance of another’s capacity to love in return.” Serene indeed.

One way to get around seeing The Giving Tree as a bad metaphor for motherhood is not to make the tree a metaphor for anything. The tree is a tree. The tree gives what trees give: shade, wood, fruit. The boy knows how to take it. If that’s the moral of the story, we need not get sad or mad at the end when the tree has nothing left to give. We can get more trees.

More trees: This year’s stamp coincides with the popularity of conscientious tree-planting as a remedy to the ravages humans have wrought on the earth. Advocacy groups now rally around the goal of planting a trillion trees. Indeed, most of us may have already contributed to this honorable goal by shopping at Amazon or shipping through UPS, just two of many companies supporting tree-planting projects.

But even a trillion trees might not be enough to save us, as Zach St. George keenly argues, pointing out the complications of that noble dream. Counting is tricky both for existing trees and new ones. Good-hearted folk plant not actual trees but seedlings which, like babies, require much care. Most compelling, not every place lacking trees is a good place to pop some in. Prairies and grasslands have their own integrity, root systems like underground forests, and can be compromised rather than enriched by these additions. Some scientists worry that maps of prime tree-planting regions look a lot like a map of the world’s great grasslands—which have enough biodiversity and challenges without having to host saplings.

Grassland scientists’ critiques cut like a scythe, revealing that even well-meaning folk may yet have that boy lurking underneath. The boy is the problem. We are the boy. The trouble is the boy’s infinite grasping, not the tree’s finite supply. Unless the boy’s character gets corrected, planting a whole lot of trees might just produce more to misuse. Crediting a Chinese saying, trillion-tree planters say the best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago, and the second-best time is now. This may reflect admirable fervor, but it betrays an innocence regarding the unintended consequences that have made other aid projects founder. We may figure out too late that taking everything a tree has to offer leaves us with nothing but a stump. We need not go, heedless, to wreck something else by trying to make ourselves more trees.

If we look sadly at the stump and rue the mess we have made of good green stuff growing from the earth, the very next response should not be taking up spade to plant something else. We might struggle to get at our own roots first. Getting at them requires admitting that we have a bigger problem to solve when we have cut to the stump. What we must do now is harder than if we had, say, stopped the boy at the branch-cutting stage.

The Silverstein commemorative stamp might serve to remind us of that, even through its ironic intended usage: pasted onto items fashioned of wood pulp.

Agnes R. Howard teaches in Christ College, the honors college at Valparaiso University, and is author of Showing: What Pregnancy Tells Us about Being Human.

Crazy timing! I just received this book in the mail yesterday and read it last night for the first time. Amazon offered a beautiful hardcover copy for about $6 to have my order qualify for Free Shipping. Though, being a child of the late 70s/early 80s I am sure it was read to me at some point. But the title was not in my childhood library. Thank you for your thoughts.

The story can mean what we want it to mean. Or it can challenge us. The latter is more helpful.

The irony of the stamp is surely a parable also.