When it comes to the witness of the church, the Christian Right brand of politics is unsustainable. The church needs other alternatives.

In my 2018 book Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump I offered a historical explanation for why roughly 81% of white evangelical voters pulled a lever for Trump in the 2016 presidential election. I still hear from readers of Believe Me, and most of them tell me they held their noses and voted for Trump because their consciences would not allow them to cast a ballot for the pro-choice feminist Hillary Clinton.

While many evangelical voters made a personal choice to choose Trump over Clinton, very few realize how history has also shaped their decisions in the ballot box. As Karl Marx famously said, “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.”

For conservative evangelicals in America the “circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past” have yielded the approach to politics forged four decades ago by the Christian Right. Indeed, it weighs on us like a “nightmare on the brain of the living.”

In 2016 the average Trump voter was fifty-seven years old. Though I have not seen a study of evangelical Trump voters, I think it is fair to say that most of them hovered around the same age. My point is this: Most evangelical Trump voters came of age in the 1980s. They learned how to do politics from the likes of Jerry Falwell, Tim LaHaye, Pat Robertson, and other leaders of the so-called Christian Right. These evangelical leaders offered their followers a political playbook designed to win America for their Christian agenda. The playbook taught ordinary evangelicals to vote for a president and members of Congress who would pass laws granting privileges to a “Christian worldview.” These elected officials would, in turn, appoint and confirm conservative Supreme Court justices who would challenge the idea of the “separation of church and state,” overturn Roe v. Wade, and defend Christian conservative values in public life. As I argued in Believe Me, fear, power, and nostalgia undergird this playbook.

The Christian Right is enjoying a period of great success. Roe v. Wade was overturned earlier this year. The Supreme Court is regularly siding with evangelicals on religious liberty cases. Justice Clarence Thomas wants to revisit decisions on same-sex marriage and birth control. Donald Trump delivered for conservative evangelicals and now many of them are hoping for more political victories in the coming midterm elections. Momentum is building as the Christian Right continues to feed its constituency a steady diet of fearmongering, Christian nationalism, and nostalgic calls for a return to a Christian golden age that never existed in the first place.

In the process few rank-and-file evangelicals are reflecting on novelist Marilyn Robinson’s reminder that fear is not a Christian habit of mind. Few rank-and-file evangelicals seem to believe that power, to quote political scientist Glenn Tinder, is a “morally problematic” idea because it almost always induces “others to serve one’s own purposes.” It objectifies other human beings and is thus, to quote Tinder again, a “degraded relationship if judged by the standards of love.” Few rank-and-file evangelicals are aware that much of the Christian Right agenda is built on a sloppy and irresponsible approach to history that manipulates the American past for political ends.

If you are a Christian and are disgusted by this brand of politics, I offer a small bit of hope. There are thoughtful evangelicals out there offering alternative visions of Christian politics. As a critic of the way my fellow evangelicals have sold their soul to the politics of Trumpism, I am often accused of offering too much in terms of critique and not enough in terms of solutions. So in response to those critics in search of something constructive, let me offer three evangelical approaches to politics that do not rely on fear, power, and nostalgia. These, of course, are not the only alternative approaches to Christian Right politics, but they are the ones that have the most appeal to me. If you find these models worthwhile, I encourage you to do more reading on one or more of them.

Faithful Presence: In 2010, University of Virginia sociologist James Davidson Hunter published To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy & Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World. Hunter argues that the dominant approach Christians employ today in their engagement with culture is activism, or the attempt to transform the world through the pursuit of political power and the moral condemnation of their enemies. According to Hunter, Christians spend a lot of money doing this but they don’t accomplish much. Yes, they win a battle or two, but such an approach will not sustain long term cultural change.

Instead, Hunter calls Christians to be faithfully present in the communities in which they find themselves. Such an approach is rooted in the Christian doctrine of the incarnation (“the word became flesh”) and the Christian’s daily witness of a God who pursues us, identifies with us, is good, true, active, intentional, and wholehearted, and is ever present in our lives. This approach requires Christians to be fully present—in a spirit of peace and love—in our families, neighborhoods, and places of employment. Only by building such local and regional networks will Christians see long-lasting and meaningful change in the world.

Catholic Social Thought. One does not have to be a Catholic to embrace Catholic social teaching as a model for political engagement. Washington Post columnist and former George W. Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson, a graduate of Wheaton College, writes out of this tradition. So does evangelical theologian Ronald Sider, author of books such as Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger and the Scandal of Evangelical Politics. Sider helped the National Association of Evangelicals craft “For the Health of the Nation: An Evangelical Call to Civic Responsibility,” a document influenced deeply by Catholic social teaching.

At its core, Catholic social teaching is concerned with the building of a just society and how Christians can pursue faithful and holy lives in the midst of the modern world. It stresses the dignity of human life, the preservation of the family, a commitment to the common good (balancing rights with responsibility to neighbor), and a public policy agenda that privileges the plight of the poor, oppressed, and vulnerable. In addition, this Catholic vision celebrates work as a means of contributing to God’s creation, champions human solidarity in a way that transcends national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences, and teaches care for the environment.

Confident Pluralism: How do we live with one another despite our deepest differences? This question drives Washington University law professor John Inazu’s 2016 book Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving through Deep Difference. Though Inazu does not frame Confident Pluralism as a Christian book, he has teamed-up on multiple occasions with evangelical theologian and pastor Timothy Keller to bring the message of his University of Chicago Press monograph to Christian audiences.

Confident pluralism, according to Inazu, requires Americans to “make room for our differences even as we maintain our own beliefs and practices.” This requires personal commitments to tolerance, humility, and patience. We must be tolerant of others’ beliefs and allow them to practice those beliefs as part of a democratic society even if we don’t embrace such beliefs personally or collectively. Humility, Inazu writes, “recognizes that we will sometimes be unable to prove to others why we believe we are right and they are wrong.” Patience asks us to “listen, understand, and empathize with those who see the world differently.”

The fact that none of these political visions has gained significant traction among American evangelicals is a testament to the success of the Christian Right. Jerry Falwell and his colleagues have forged the most consequential political movement in post-World War II American history. They taught millions and millions of Americans that there is only one way to do Christian politics. The political instincts of most American evangelicals have not changed since 1980. In 2016 Donald Trump understood this better than most. Sometimes the past can have its way with us.

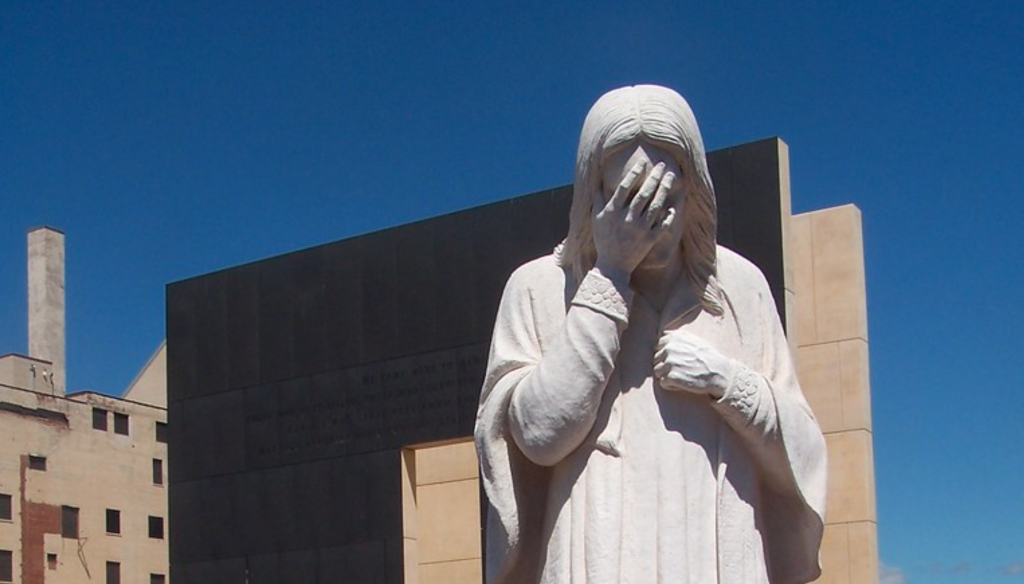

An evangelical political playbook defined by fear, power, and nostalgia is likely to deliver many more political wins for the Christian Right. But when it comes to the future witness of the church and its ability to be salt and light in the culture, the Christian Right approach to evangelical public engagement is unsustainable. With every political victory the Christian Right is in danger of becoming less and less Christian.

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current.

These are great of course but none of them produce the power that the Christian Right longs for.

John, which of the things that you and your allies have proposed contradicts the worldview of the Washington, D.C., political establishment? My sense is that you, Ron Sider, and others are quite comfortable in that political atmosphere and that while you may reject what the right is calling Christian nationalism, you are calling for your own version of the same, that being an all-powerful state that uses coercion to suppress opposing views. For example, your party is actively promoting an atmosphere is schools in which young adolescents are being pressured into calling themselves transgenders and parents that object to their children wanting to “transition” are visited by Child Protective Services and their rights as parents are threatened by the law.

Yes, I thoroughly object to what is happening in many evangelical churches that are pursuing Christian nationalism or making wild proclamations about Donald Trump. I have no association with such groups and will not become part of them. But I also can understand why churches are moving in this direction. They see people like you endorsing a political party and ideological movements that cannot in any world be seen as Biblical or even decent. Yes, you might editorialize against abortion, although you do it in a way to try to keep your Democratic fellows from becoming too angry with you. But do you believe that young children should be given puberty blockers, teenage girls have their breasts cut off, and young men castrated, all endorsed by the Democratic Party and supported by your president? Where does this all end?

William, what political party is John promoting in this piece? You’re making an accusation, but you’re not providing any proof. You’re not citing anything… (This btw is part of the Religious Right playbook… claim things… without actual cited proof… their herd laps it up – but I/we don’t.)

I agree J.

As I do with John’s closing thoughts:

“An evangelical political playbook defined by fear, power, and nostalgia is likely to deliver many more political wins for the Christian Right. But when it comes to the future witness of the church and its ability to be salt and light in the culture, the Christian Right approach to evangelical public engagement is unsustainable. With every political victory the Christian Right is in danger of becoming less and less Christian”