There’s more art history than you realize in your old children’s Bibles

“David and Bathsheba” returned to trending status on Twitter again. Users were arguing—with varying degrees of success—over the implications of saying that Bathsheba was “raped” rather than that she “committed adultery.”

But as Old Testament scholar Carmen Joy Imes demonstrates, the debate itself reveals more about our contemporary culture than David’s. If we’re not careful we can miss the ways the narrative both assumes and then disrupts ancient Near Eastern expectations of patriarchy and kingship. Imes encourages us to take stock of the ways our cultural frameworks might impair our ability to see what’s in front of us.

In fact, the ways we have literally seen Bathsheba might be part of the challenge.

Like many young evangelicals who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s I had a range of children’s Bibles, many of which favored naturalistic illustrations. As I recently clicked through digitized versions of The Doubleday Illustrated Children’s Bible (1983), The Children’s Bible: In 365 Stories (Lion 1987), and The Children’s Illustrated Bible (DK 1994) looking for pictures of Bathsheba, I experienced a double déjà vu. The illustrations were familiar because I had seen them as a child, but by that time I had also seen their predecessors in my art historical studies.

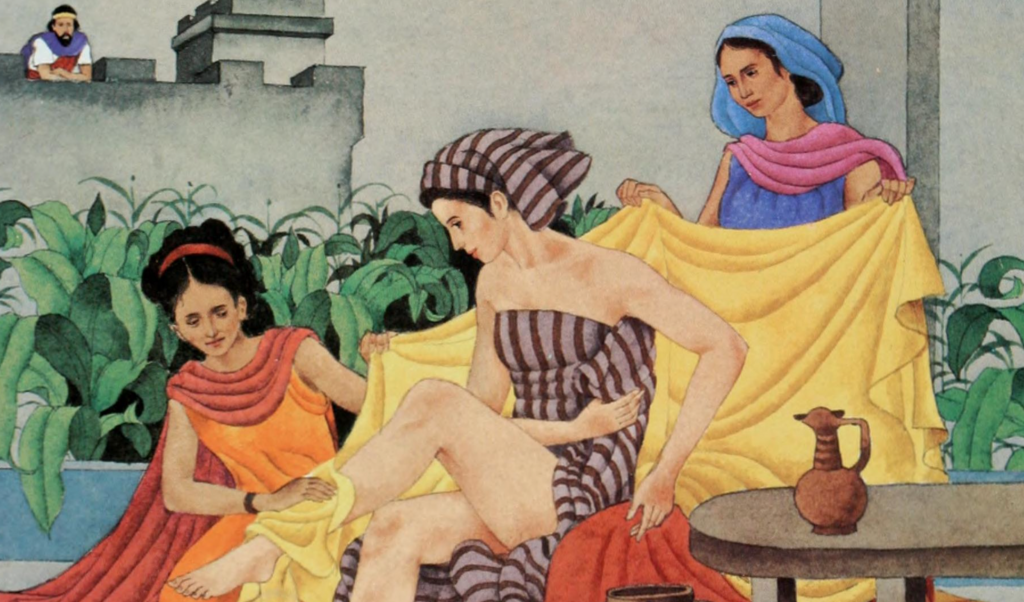

The clearest example comes from The Doubleday Illustrated Children’s Bible written by Sandol Stoddard and illustrated by Tony Chen in 1983. In a full-page, colored illustration, we see Bathsheba seated next to a small tub and table, seemingly on a porch or veranda edged with lush foliage. Two maids attend her; one stands to the right, holding a large yellow towel while the other woman kneels to the left, wiping Bathsheba’s feet. Meanwhile, with her hair and body wrapped in matching, striped purple towels, Bathsheba herself could have stepped out of a contemporary women’s razor ad. Her arms and upper chest are bare, and we see practically the entire length of her slim legs as she extends them towards her kneeling servant. In the background, near the upper left corner, we see a tiny King David leaning over his palace parapet and gazing at the women.

The composition of this children’s illustration is almost identical to a number of earlier paintings of Bathsheba at her bath from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The women’s bodies form a similar triangle in a late career painting by Artemisia Gentileschi, a 1720s painting by Sebastiano Ricci, a 1750 depiction by Jean François de Troy, as well as numerous other now-anonymous works. In each of these paintings the artist uses light and line to direct our attention to Bathsheba’s bare skin. Likewise, every painting shows David hovering in the distance, unabashedly staring at the naked or partially draped Bathsheba.

The Doubleday image is also eerily similar to another repeated scene in western art history: the toilette of Venus. Painters from Guido Reni to François Boucher depicted the mythological goddess of love and beauty partially draped and lounging idly as other figures eagerly attended to her. In these formulations, there is no peeping Tom in the background. Instead, the viewer becomes the voyeur, receiving pleasure from that which ostensibly should remain private. Perhaps even more unexpected is the realization that both these mythological paintings and depictions of Bathsheba anticipate the visual template of Gillette’s Venus razor advertisements from the early 2000s! “I’m your Venus,” a woman sings as we tumble through a montage of silky smooth legs.

These similarities matter because the children’s text, like the original, leaves narrative holes. Biblical scholars agree that the account of 2 Samuel 11-12 is riddled with purposeful gaps. Sara M. Koenig describes some of these interpretive challenges in her book Bathsheba Survives. Why isn’t David at war with his troops? Does Bathsheba know that she is visible? Does Bathsheba come willingly or by force? What is she hoping for when she tells David that she is pregnant? Did Bathsheba love Uriah? Does she want to marry David? Koenig goes on to argue that all readers of 2 Samuel from Talmudic rabbis to early church fathers, medieval scholars, Reformation theologians, and Enlightenment skeptics use their own cultural knowledge and assumptions to help fill in the gaps of the biblical narrative.

The text of the children’s Bible retains many of the uncertainties from the original. But it also creates a new gap by remaining especially vague over which of God’s commandments the prophet Nathan accuses David of breaking. The parable of the poor man’s lamb is entirely omitted from the rewritten story.

But the young reader is not left entirely to her own hermeneutical devices. The illustration offers to fill in some of the missing pieces, encouraging us towards a certain understanding of Bathsheba and David’s relationship.

Despite her towel, the Doubleday Bathsheba—like Venus—is presented as an object for us to gaze upon. The two maids and the saffron drape focus our attention, and the lines of Bathsheba’s bent arms and legs guide our eyes on a meandering path down her body. Ironically our point of view as readers allows us to see more of Bathsheba than David can. And since she seemingly offers herself to us visually it can be easy to assume that she does the same with the king.

In fact, in The Children’s Bible: In 365 Stories Bathsheba is shown walking confidently and unassisted into David’s throne room while a male messenger watches from behind a curtain. And in The DK Children’s Illustrated Bible the illustration completely collapses the distance between David’s roof and Bathsheba’s garden-like courtyard thus visually eliminating the possibility of her resistance as well. David is certainly not guiltless in any of these images, but Bathsheba is visualized as sharing some culpability.

I point this out not to attribute malicious intent to children’s Bible illustrators, but to acknowledge that western visual culture has already taught us to imagine and to reiterate Bathsheba’s story in a certain way. Though somewhat more circumspect than the Bathshebas of medieval manuscripts—apparently shameless seductresses who bathe in the open—the Doubleday Bathsheba reinforces still-powerful cultural tropes. The image encourages the reader to fill in the narrative thusly: Men become foolish creatures when blinded by lust and women use their sexuality to advance their position. Thus, both are to blame.

There are numerous resources outside of Twitter that can help an interested reader build a robust understanding of this biblical narrative. But before we can begin to grasp the multiple ways that an ancient text can provide contemporary wisdom, we would do well to acknowledge the images that already live in our heads.

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt is Associate Professor of Art and Art History at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, GA.