In the lives of great writers we touch divinity and face humanity

One summer when I was a kid my family took a vacation to Massachusetts. The ultimate destination was a cottage on Cape Cod but my dad, an English teacher and a great fan of the American Romantics and Transcendentalists, took us on a detour to Walden Pond, where 140 or so years earlier Henry David Thoreau had gone “to the woods” because he “wished to live deliberately.” How old I was at the time, I can’t remember—somewhere in elementary school—but my sister and I played on a giant moss covered boulder while my dad and mom went to venerate the site of the cabin and the pond itself. The site of the actual cabin in the woods, by the actual pond where Thoreau actually lived.

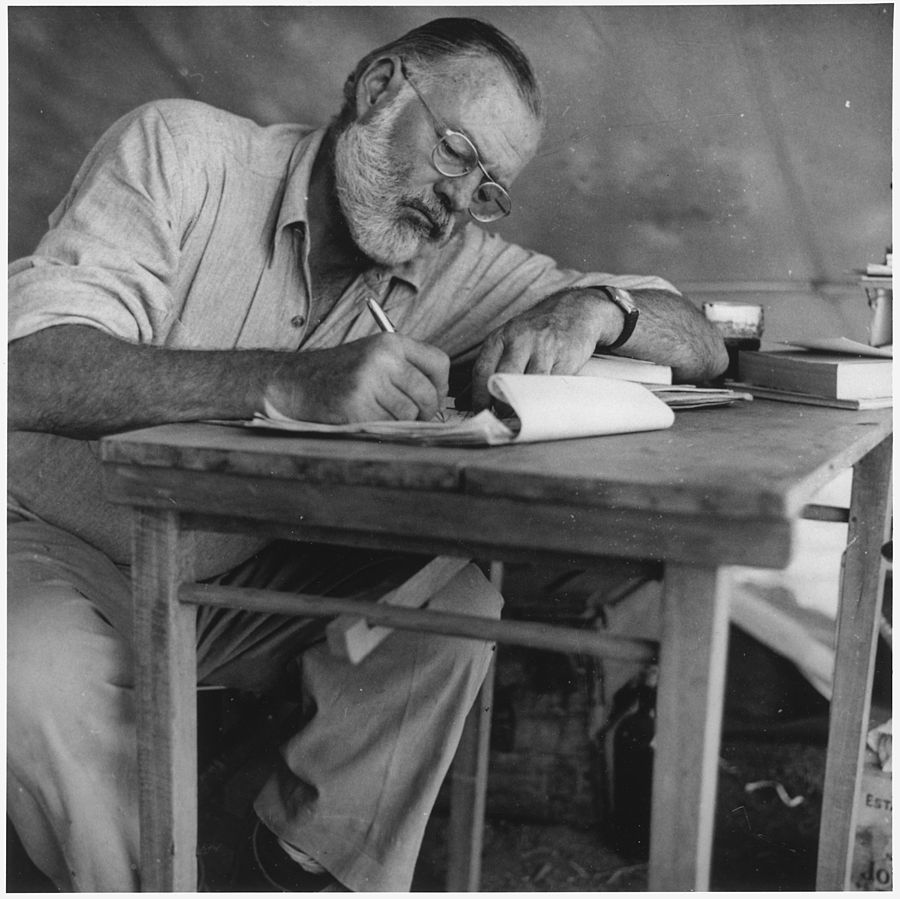

Years later, when I lived in Chicago with my wife and the first of our daughters, we three visited the house (now a museum) in Oak Park, Illinois where Ernest Hemingway was born. A museum staffer explained that the furnishings and many other items in the house were replicas of what would’ve likely been there at the turn of the century (Hemingway’s date of birth: July 21, 1899), but that the floor tiles in the kitchen were original to the house.

“Hold it,” I said, my brain suddenly filling with wonder brighter than sunshine. “So, that would mean Ernest Hemingway actually touched this floor.”

“Sure,” the staffer said, with not a small amount of ‘duh’ in her tone. “Probably crawled across it as a baby.”

The thought of Hemingway’s actual chubby baby hands—hands that would grow into adult hands that would type up a Nobel Prize winning literary career, not to mention slug Wallace Stevens in the face one drunken night in Key West—on the actual floor on which I was actually standing during that visit left me gob-smacked. The space between Ernest Hemingway and me felt suddenly, uncomfortably small—his legend and profound literary contributions of course, but also, strikingly, his humanity.

For Whom the Bell Tolls and “Hills Like White Elephants,” and everything else Hemingway ever wrote, up to and including his grocery lists (“Whiskey. Meat, any kind. Fish hooks.”) have always seemed like sacred texts to me. I don’t mean they’re perfect in every sense of the word (though a case for all-around perfection regarding “Hills Like White Elephants” could be reasonably made). But insofar as his writing, and his thoughts on writing, and the life that he lived as a writer, lock themselves tighter to world literature with the passing of each generation, it seems somehow unlikely that his works came from a very human mind, one addled by depression and booze and war. There must have been some Divine intervention, right? If not that, at least a cadre of conscripted MFA grad students laboring night and day over their typewriters—just as Shakespeare’s stuff was actually written by ten disciples of Christopher Marlowe. It just doesn’t seem humanly possible to be that consistently good.

That visit to Hemingway’s birth home brought me into proximity with a superhuman power (as it must have done for my dad at Walden Pond) that is both irresistible and horrific. To know Hemingway, Thoreau, or any other literary author by his/her written work is one kind of knowledge, but in fact, their works have achieved their respective canonical statuses not because we’ve gotten to know the authors through their works but because we’ve come to know ourselves more authentically via the roads the authors have paved with their words through our hearts and minds. Who but somebody wielding the power of a god could so illuminate a soul? And once I look upon a god, via the god’s work, I tend never to want to look back at the baseness of plain humanity. I can’t know myself ever again outside of the enlightened state to which the author has transported me.

But, of course, I have no choice but to rejoin the baseness of humanity, despite the transcendent experience of the read, since I myself embody base humanity. Sojourns to the geographic locales where the likes of Thoreau and Hemingway were born or came to the revelations they translated into literature remind me that not only were these great creators actual human beings (and not at all divine) but, critically, that I also am flesh and blood, skin and bones, and sub-divine.

And yet, standing there on Hemingway’s kitchen floor, I was all the more aware of everything he did when he was alive. Suddenly my own bare potential was upon me, and nothing in the world is more inviting or abhorrent.

Now that I live in East Tennessee I’ll soon be making a pilgrimage to Flannery O’Connor’s Andalusia Farm, about three-and-a-half hours south, to lay eyes on—and maybe pet!—the actual peacocks and peahens who live there now, descendants of O’Connor’s actual fabled peafowl. I may journey north an hour or so too, to the house in the woods where Cormac McCarthy once lived and, evidently, hand built the chimney. I may or may not even steal an actual brick from that chimney, or at least chip off a few flakes of the tuckpointing—my own little relics. The intimacy this kind of veneration provides makes for a tense but balanced co-existence. At Walden Pond, or Hemingway’s birthplace, or Andalusia, or McCarthy’s cabin, I stand calf-deep in the mud of humanity, where I most certainly belong. But there eternity swoops past and I take a breath from its wake.

Paul Luikart is the author of the short story collections Animal Heart (Hyperborea Publishing, 2016), Brief Instructions (Ghostbird Press, 2017), Metropolia (Ghostbird Press, 2021) and The Museum of Heartache (Pski’s Porch Publishing, 2021.) He serves as an adjunct professor of fiction writing at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia and lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee.