Mark Glanville of Regent College (Vancouver, B.C.) explains:

The recent Guidepost Solutions report on sexual abuse in the Southern Baptist Convention revealed that August Boto, a key leader on the SBC Executive Committee, labeled the work of advocates on behalf of survivors of sexual abuse as a “satanic scheme to completely distract us from evangelism,” in an internal email. “It is not the gospel. It is not even a part of the gospel. It is a misdirection play,” Boto wrote.

Boto’s branding of this advocacy work as a satanic scheme is horrific. Silencing and vilifying survivors and their advocates in the name of Christ does damage to the faith of survivors and the soul of the church. However, I want to zero in on something else he said: his hard distinction between the gospel and advocacy for justice. Why do evangelical leaders so often condemn the second as a distraction from the first?

Antiracism work has been criticized by Christians in similar ways. For example, in a public dialogue on “woke church” hosted by the Gospel Coalition, a pastor derided “wokeness, critical theory and social justice activism” as “gospel compromise.”

Other censures are subtler. In a sermon I was present for, a well-known leader first acknowledged that racism is indeed evil. And yet, he urged, the church should stay focused on the gospel. Too much attention to racism is a “distraction from the gospel.” While this sermon may appear less offensive on the surface than some others, it is also more difficult for the person in the pew to untangle.

Perhaps this is the rift that a lot of activists do not understand: When the gospel is defined narrowly as Christ’s work on behalf of sinners—and gospel work as evangelism—then while a little social justice may be acceptable, a lot may be a distraction. Others, perhaps more thoughtfully, may understand the gospel as the Lordship of Christ. Yet if Christ’s Lordship is shorn of any ethical content, the rift remains.

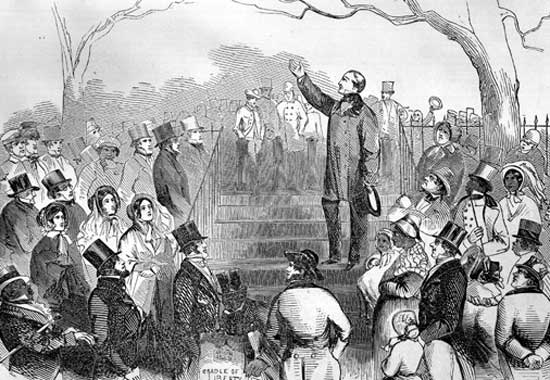

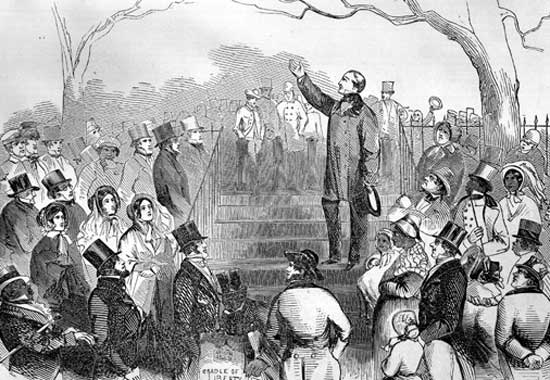

This distraction argument is not new. Similar cases were made against the abolition movement’s call for the end of slavery in the United States.

Early 19th-century White Christians had a diversity of opinions on slavery. And yet, as historian Ben Wright writes, “Nearly all denominational leaders actively denounced abolitionists as opponents of American salvation.”

White Christian leaders tended to favor what Wright calls “conversionism” over the “purificationism” of the abolitionists. Conversionism meant evangelizing the nation and the colonies—including slaves. “Conversionism became the core of proslavery Christianity,” says Wright.

Read the rest at the Christian Century.

I am reminded here of the words of N.T. Wright in Surprised by Hope:

It’s no good falling back into the tired old split-level world where some people believe in evangelism in terms of saving souls for a timeless eternity and other people believe in mission in terms of working for justice, peace, and hope in the present world. That great divide has nothing to do with Jesus and the New Testament and everything to do with the silent enslavement of many Christians (both conservative and radical) to the Platonic ideology of the Enlightenment. Once we get the resurrection straight, we can and must get missions straight. (p.193).