A Soviet childhood leaves its traces on the heart—even as the mind wonders why

As Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine continues, Russian President Vladimir Putin has stepped up his propaganda game. But as with everything he has ever done, he has not needed to think outside a very obvious box. Drawing on the rich legacy of propaganda in the Soviet State, Putin has, for instance, invested in putting up portraits of himself in school classrooms. While not directly ordered by Putin, one region has even invested in special tactile 3D portraits of the “Trinity”—Putin, Stalin, and Trump—for blind children. This intimacy of knowing your leader with your caressing hands, instead of eyes watching from afar, is meant to remind the children that their leader cares for them, as presumably do his dear friends Stalin and Trump. But this type of messaging, while warped, is nothing new to Russia.

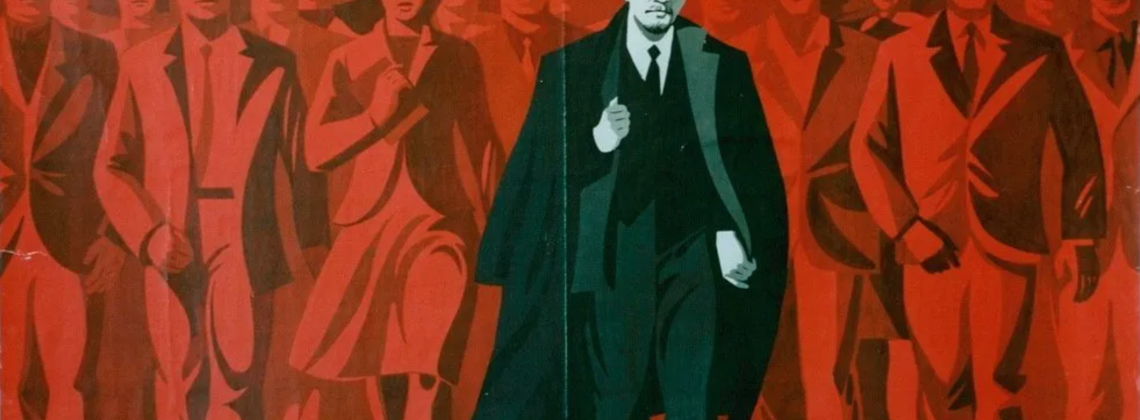

On the back wall of my first-grade Russian classroom there was a portrait of Vladimir Ilych Lenin. He was smiling benignly at us, the country’s future. Living in Leningrad, the city named after the leader, seeing his face every day, and reading short stories about his love for children as we were solidifying our fledgling reading skills, it felt like we really knew him. Furthermore, although he had been dead for well over a half-century by the time my classmates and I were born, the stories seemed to imply that this great leader himself knew us and cared for us too.

I remember one short story we read in which Lenin dressed up as the secular Russian equivalent of Santa, Ded Moroz (Grandpa Frost), for New Year festivities, to the delight of children in attendance. We were encouraged to refer to Lenin as “Grandpa Lenin,” just as the short stories we read did. He was, after all, the loving and doting grandfather of the entire Soviet state. Then following the mandatory-for-all induction as members of Oktyabryata (Children of October) in the third grade, I got to wear the pin with Lenin’s image on my school uniform every day. It was presented to us as a privilege—although it was, of course, a requirement.

Not long after that induction my family immigrated to Israel. There no one cared about Grandpa Lenin. It was a little confusing at first, but not for long. When moving to another country, with a completely different language and culture, after all, there are plenty of other things about which to be confused. If I no longer had to worry about Grandpa Lenin’s watchful eye, that was fine by me.

Looking back upon my Soviet elementary school education with the eyes of a professional historian, I now see with amusement mixed with dismay all the elements of indoctrination into a state religion, with Lenin as its chief patron saint. And just as Lenin lived and died for the Soviet state, so were we all encouraged to think about our own obligations to the state.

It is no coincidence that one of the biographies we read was that of Pavlik Morozov, the boy who dutifully turned his own father in to the Communist Party in 1932 when he learned that his father was a traitor to the Soviet state. The story ended in tragedy: Pavlik’s father was executed. This was, after all, 1932, when most offenses resulted in a death sentence. Then his relatives killed Pavlik—and were almost all subsequently executed as well.

This outcome only served to solidify Pavlik’s standing in the pantheon of Soviet martyrs, perhaps. He gave his life for the state. Or so reminded the short stories, poems, songs, and even operas composed about this boy, who became more legend than reality immediately after his death. In other words, being a child was no exemption from opportunities for heroism or obligations to the state. You too can serve the state by spying on your own relatives and turning them in if they go astray. It is for their own good anyway, as well as for the good of the state.

Putin shares a first name with Lenin: the very popular Russian first name, Vladimir. Born in 1952, a mere seven years after the conclusion of the Great Patriotic War, as WWII is known in Russia, he is of my parents’ generation. And so, like my parents, he grew up in the days of closed borders, whispered secrets, and fear all around, caused by ghosts. The arrests, the deportations to the Gulags, and the secret executions, after all, were still all too real. And then there was the poverty of a country drained of all resources by the prolonged war from which it had just recently emerged.

For young Vladimir Putin—for while we only think of him as a ruthless dictator and murderer, he too was a child once—Lenin may well have been the ghost of a loving grandpa. Meanwhile Stalin, who died when Putin was just a few months old, was for the adults around him the ghost of horrors that just could not be forgotten, although no one could quite bring themself to talk about them either. But when faced with ghosts of such incredible power, one could also treat them as examples to emulate rather than eschew. Is it possible that even then, when looking at those portraits of Lenin and Stalin at the back of the classroom, his main thought was: Someday, it will be my portrait there?

It has been thirty-one years since I left Russia, and I have not been back. And yet emotional wiring is set in childhood in such a way that we can feel attachment and nostalgia for things we know to be false. Could this be because the shape in which we learned these things seemed, in the eyes of a child, so lovely? To be clear, I have no attachment to Grandpa Lenin—even as a child, I thought the whole thing was weird and unnecessary. I had one loving grandfather nearby and felt no need to look for a creepy emotional substitute, whom the teachers seemed to try to impose on the class so unconvincingly. But sometimes I hear a certain song, and the tears flow freely. It feels strangely emotional to think that the city in which I was born, Leningrad, does not exist anymore under that name. Edita Piekha, the Polish transplant who became a star Russian pop singer of the post-WWII era, concludes the refrain of her ode to Leningrad and its famous white nights, “If you, from your young years have lived in Leningrad, you will understand, dear friend, you will understand.”

Nadya Williams is Professor of Ancient History at the University of West Georgia. She is a Contributing Editor for Current.